Various studies have identified factors associated with risk of mortality in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, their sample size has often been limited and their results partially contradictory. This study evaluated factors associated with COVID-19 mortality in the population of Madrid over 75 years of age, in infected patients, and in hospitalized patients up to January 2021.

Patients and MethodsThis population-based cohort study analyzed all residents of the Community of Madrid born before January 1, 1945 who were alive as of December 31, 2019. Demographic and clinical data were obtained from primary care electronic medical records (PC-Madrid), data on hospital admissions from the Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos (CMBD, Minimum Data Set), and data on mortality from the Índice Nacional de Defunciones (INDEF, National Death Index). Data on SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization, and death were collected from March 1, 2020 to January 31, 2021.

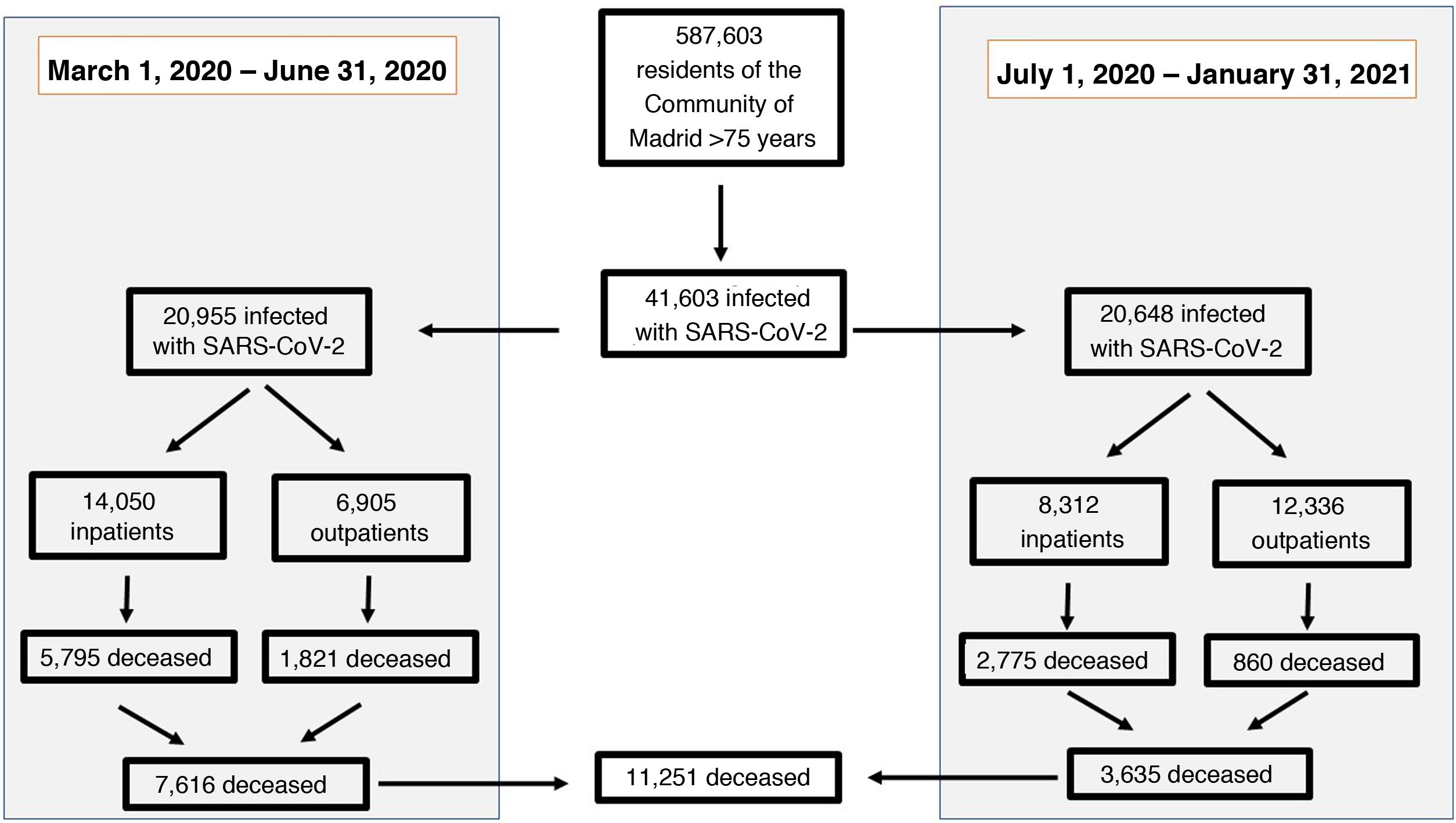

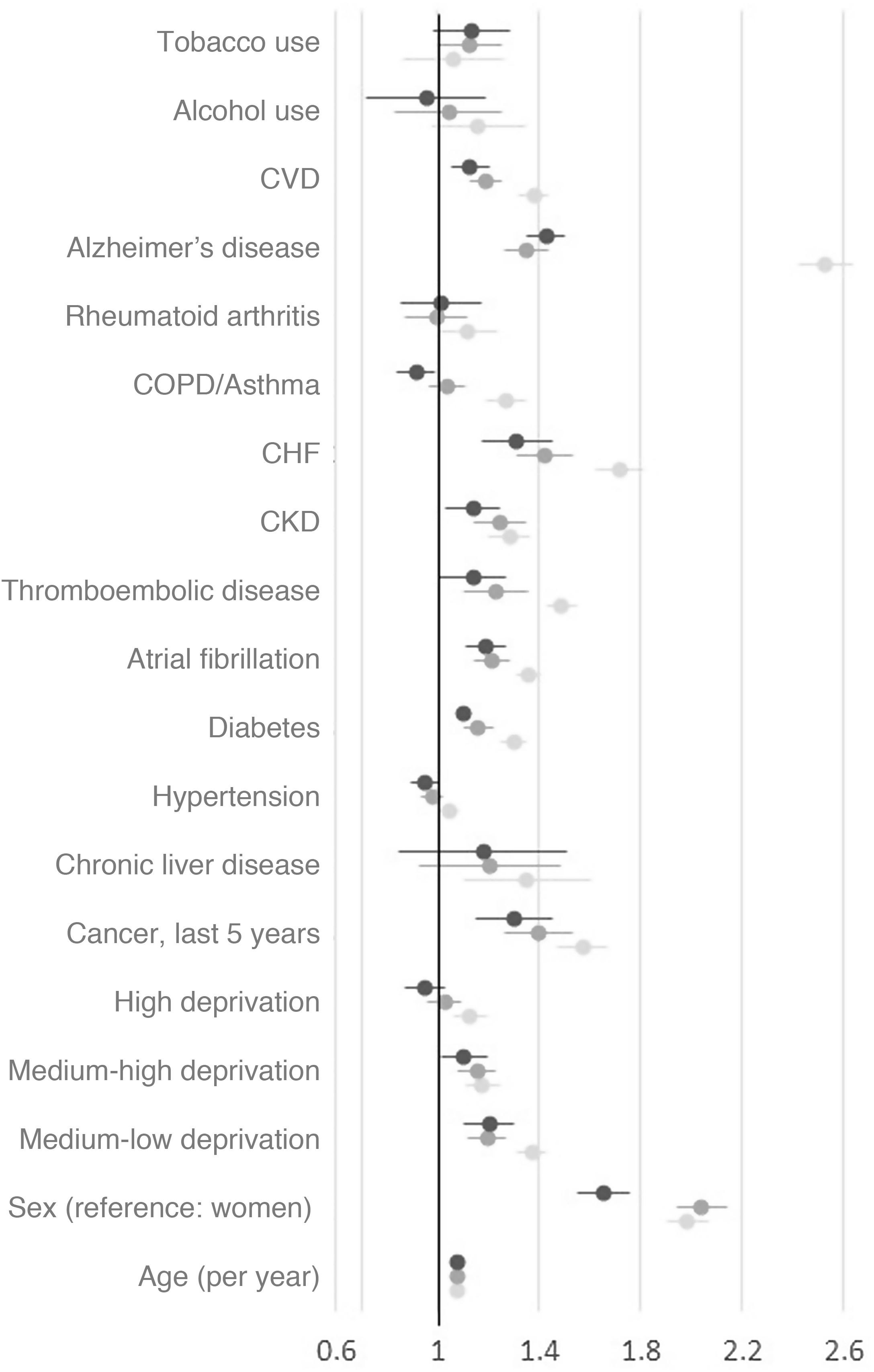

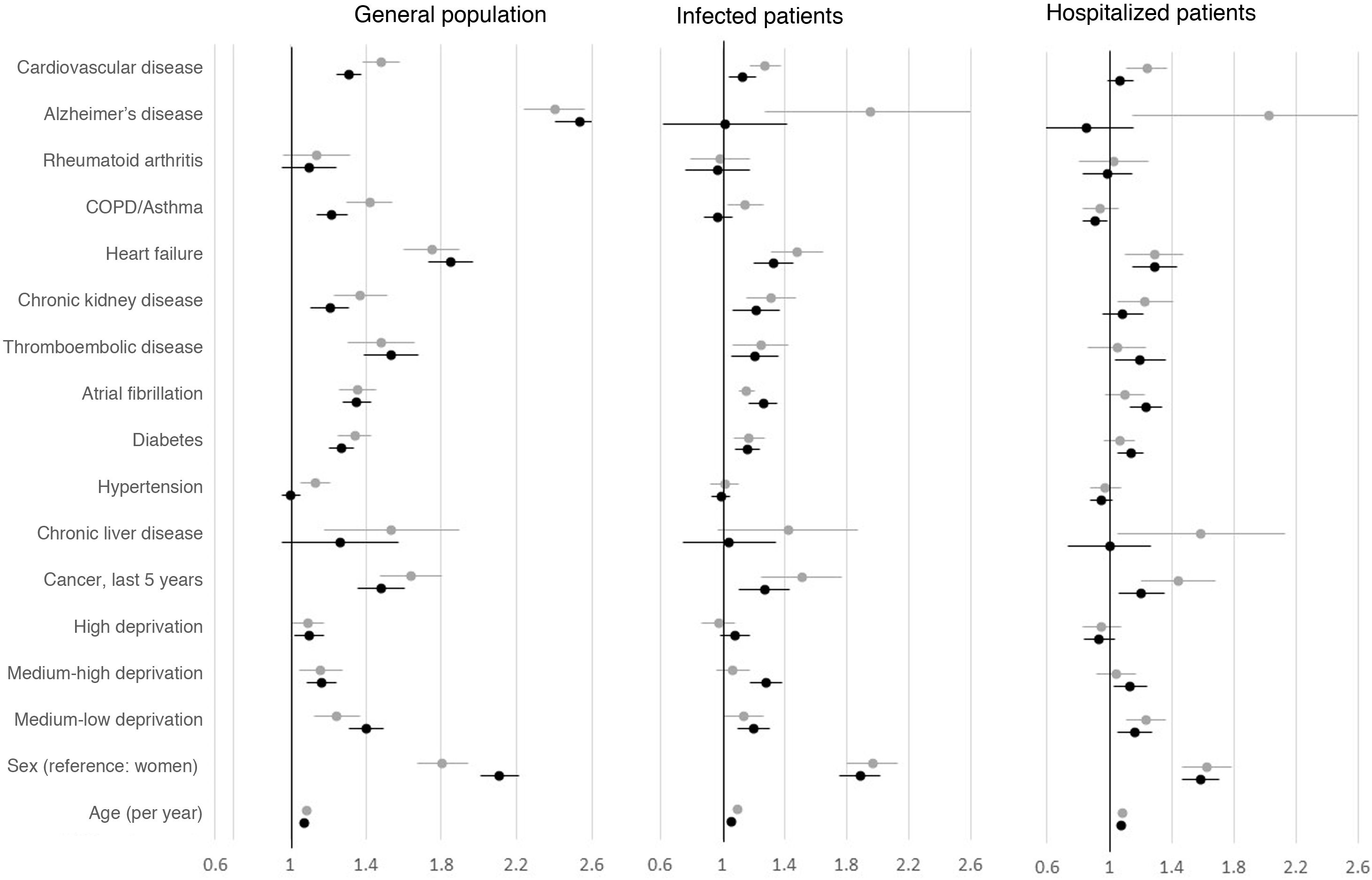

ResultsA total of 587,603 subjects were included in the cohort. Of them, 41,603 (7.1%) had confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, of which 22,362 (53.7% of the infected individuals) were hospitalized and 11,251 (27%) died. Male sex and age were the factors most closely associated with mortality, though many comorbidities also had an influence. The associations were stronger in the analysis of the total population than in the analysis of infected or hospitalized patients. Mortality among hospitalized patients was lower during the second wave (33.4%) than during the first wave (41.2%) of the pandemic.

ConclusionAge, sex, and numerous comorbidities are associated with risk of death due to COVID-19. Mortality in hospitalized patients declined notably after the first wave of the pandemic.

Diversos estudios han identificado factores asociados con el riesgo de muerte en pacientes infectados por SARS-CoV-2. Sin embargo, su tamaño muestral ha sido muchas veces limitado, y sus resultados parcialmente contradictorios. Este estudio ha evaluado los factores asociados con la mortalidad por COVID-19 en la población madrileña mayor de 75 años, en los pacientes infectados y en los hospitalizados hasta enero de 2021.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio de cohortes de base poblacional con todos los residentes de la Comunidad de Madrid nacidos antes del 1 de enero de 1945 y vivos a 31 de diciembre de 2019. Se obtuvieron variables demográficas y clínicas de la historia clínica electrónica de atención primaria (AP-Madrid), de los ingresos hospitalarios a través del Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos (CMBD) y de la mortalidad a través del Índice Nacional de Defunciones (INDEF). Se recogieron los datos de infección, hospitalización y muerte por SARS-CoV-2 entre el 1 de marzo de 2020 y el 31 de enero de 2021.

ResultadosDe los 587.603 sujetos incluidos en la cohorte, 41.603 (7,1%) desarrollaron una infección confirmada por SARS-CoV-2. De ellos, 22.362 (53,7% de los infectados) se hospitalizaron y 11.251 (27%) murieron. El sexo masculino y la edad fueron los factores más asociados con la mortalidad, si bien también contribuyeron numerosas comorbilidades. La asociación fue de mayor magnitud en los análisis poblacionales que en los análisis con pacientes infectados u hospitalizados. La mortalidad en los hospitalizados fue menor en la segunda ola (33,4%) que en la primera ola (41,2%) de la pandemia.

ConclusiónLa edad, el sexo y las numerosas comorbilidades se asocian con el riesgo de muerte por COVID-19. La mortalidad en los pacientes hospitalizados se redujo apreciablemente después de la primera ola de la pandemia.

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<