cardiovascular changes during pregnancy carry greater risk in heart disease. We analyze cardiovascular, obstetric and perinatal adverse effects associated with congenital and acquired heart disease during pregnancy and postpartum.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional and retrospective study, which included the 2017–2023 registry of pregnant or postpartum patients hospitalised with diagnosis of congenital or acquired heart disease. Adverse events (heart failure, stroke, acute pulmonary edema, maternal death, obstetric haemorrhage, prematurity and perinatal death) were compared with the clinical variables and the implemented treatment.

Results112 patients with a median age of 28 years (range 15−44) were included. Short circuits predominated 28 (25%). Thirty-six patients (32%) were classified in class IV of the modified WHO scale for maternal cardiovascular risk.

Heart failure occurred in 39 (34.8%), acute lung edema 12 (10.7%), stroke 2 (1.8%), maternal death 5 (4.5%), obstetric haemorrhage 4 (3.6%), prematurity 50 (44.5%) and perinatal death 6 (5.4%). Shunts were associated with prematurity (adjusted odds ratio 4; 95% CI: 1.5−10, p = 0.006). Peripartum cardiomyopathy represented higher risk of pulmonary edema (adjusted OR 34; 95% CI: 6−194, p = 0.001) and heart failure (adjusted OR 16; 95% CI: 3−84, p = 0.001). An increased risk of obstetric haemorrhage was observed in patients with prosthetic valves (adjusted OR 30; 95% CI: 1.5−616, p = 0.025) and with the use of acetylsalicylic acid (adjusted OR 14; 95% CI: 1.2–16, p = 0.030). Furthermore, the latter was associated with perinatal death (adjusted OR 9; 95% CI: 1.4−68, p = 0.021).

Conclusionssevere complications were found during pregnancy and postpartum in patients with heart disease, which is why preconception evaluation and close surveillance are vital.

los cambios cardiovasculares del embarazo conllevan mayor riesgo en cardiópatas. El objetivo fue analizar los efectos adversos cardiovasculares, obstétricos y perinatales asociados a cardiopatía congénita y adquirida durante el embarazo y puerperio.

Materiales y métodosEstudio transversal y retrospectivo, que incluyó el registro de 2017–2023 de pacientes embarazadas o puérperas hospitalizadas con diagnóstico de cardiopatía congénita o adquirida. Se compararon los eventos adversos (falla cardiaca, evento vascular cerebral (EVC), edema agudo pulmonar, muerte materna, hemorragia obstétrica, prematuridad y muerte perinatal) con las variables clínicas y el tratamiento implementado.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 112 pacientes con mediana de edad de 28 años (rango 15−44). Predominaron los cortocircuitos 28 (25%). Treinta y seis pacientes (32%) se clasificaron en clase IV de la escala modificada de la OMS para riesgo cardiovascular materno.

Presentaron falla cardiaca 39 (34,8%), edema agudo de pulmón 12 (10,7%), EVC 2 (1,8%), muerte materna 5 (4,5%), hemorragia obstétrica 4 (3,6%), prematuridad 50 (44,5%) y muerte perinatal 6 (5,4%).

Los cortocircuitos se asociaron con prematuridad (odds ratio ajustado 4; IC 95%: 1,5-10, p = 0,006). La miocardiopatía periparto tuvo un mayor riesgo de edema agudo pulmonar (OR ajustado 34; IC 95%: 6–194, p = 0,001) y falla cardiaca (OR ajustado 16; IC: 95%: 3–84, p = 0,001). Se observó un aumento del riesgo a hemorragia obstétrica en pacientes con prótesis valvulares (OR ajustado 30; IC 95%: 1,5–616, p = 0,025) y al uso de ácido acetil salicílico (OR ajustado 14; IC 95%: 1,2–167, p = 0,030). Además, este último se asoció a muerte perinatal (OR ajustado 9; IC 95%: 1,4–68, p = 0,021).

ConclusionesSe encontraron complicaciones severas durante el embarazo y puerperio en cardiópatas, por ello es vital la evaluación preconcepcional y vigilancia estrecha.

The association between pregnancy and pre-existing heart disease or its onset during pregnancy is the leading cause of indirect maternal mortality.1 This is due to the fact that 85% of paediatric patients with congenital heart disease survive to adulthood, thereby increasing the incidence of pregnancies complicated by cardiovascular diseases2,3; this is also in part due to the increase in age of first-time mothers, with an age range ranging between 28.8 and 31.2 years.4

In Western studies, congenital heart disease represents 75–82% of heart disease during pregnancy, while in non-Western countries rheumatic heart disease is the main cause.5,6

In our country, in 2005, congenital and acquired heart disease was responsible for almost one fifth of all maternal deaths.7

Pregnancy induces multiple changes in the cardiovascular system. A significant increase in cardiac output of up to 45% occurs by 24 weeks’ gestation (WG). A 5−10 mmHg drop in blood pressure also occurs, reaching its lowest point in the second trimester.8 Heart rate increases by 10–20 bpm, reaching its highest point during the third trimester. On the other hand, contractility and left and right ventricular ejection fractions do not appear to change.9

These physiological changes take on increased importance within the context of heart disease, which is present in 1%–4% of pregnancies globally.10 It presents a higher risk of premature birth, pre-eclampsia, postpartum haemorrhage, and neonatal death.5,11

Due to these physiological changes, all women with known heart disease who wish to embark on pregnancy require adequate pregnancy counselling beforehand.12

The objective of this study was to evaluate cardiovascular adverse events such as heart failure, cardiovascular accident (CVA), and acute pulmonary oedema; obstetric events such as maternal death and obstetric haemorrhage; perinatal events such as perinatal mortality and prematurity; and events associated with congenital and acquired heart disease during pregnancy and the postpartum period. We also describe medical, interventional, and surgical treatments implemented during pregnancy or postpartum and their association with the reported outcomes.

Materials and methodsAn observational, cross-sectional, retrospective study. We included in a consecutive manner pregnant or postpartum patients of any age hospitalised with a diagnosis of congenital or acquired heart disease during the period between January 2017 and March 2023 in a tertiary hospital. Out of a total of 121 pregnant or postpartum patients referred to our centre during said period with a diagnosis of congenital or acquired heart disease, 72 patients (59.5%) were referred by out-patient services and 49 (40.5%) were referred by emergency services. Of those, nine patients (7.3%) were excluded due to incomplete information, resulting in 112 included patients.

The following baseline characteristics were recorded for the study population: age (divided into ranges according to the definitions for pregnancy in adolescents and advanced maternal age),13 weeks’ gestation at the first assessment, clinical history of DM2 diagnosis, chronic arterial hypertension, rheumatic disease, pulmonary hypertension, gestational DM, pre-eclampsia, number prior of pregnancies, births, caesarean sections, and miscarriages; type of congenital or acquired heart disease, levels of N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP higher and lower than 1000 ng/L), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF higher or lower than 54%), and pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP).

The following were also listed: modified WHO classification and pregnancy outcome, moment of outcome, medications used, and heart disease management (surgery or interventional treatment) performed before, during, or after the pregnancy.

The cardiovascular events assessed were heart failure (defined as decline in NYHA classification functional class), CVA, and acute pulmonary oedema (defined as signs and symptoms of heart failure requiring advanced airway management or emergency abortion).

The obstetric adverse events assessed were obstetric haemorrhage (established as bleeding exceeding 500 mL postpartum and exceeding 1000 mL post-caesarean), and maternal death (established as cardiac death during pregnancy and within the first 30 days postpartum).

The neonatal adverse events analysed were preterm birth defined as late (≤36 WG), moderate (<34 WG), very preterm (<32 WG), and neonatal mortality (death during the first seven days of life).

Absolute values and percentages were calculated for the categorical variables, and median and range for continuous variables. The comparison between cardiovascular, obstetric, and neonatal adverse events was conducted using Chi2 and a multivariate analysis via binary logistic regression was conducted to determine possible spurious values. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) was estimated as a measure of association. A statistical significance level of p < 0.05 was considered and the SPSS statistics 22 package was used.

This study adhered to institutional regulations as well as the ethical principles of research and the provisions of the declaration of Helsinki. The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

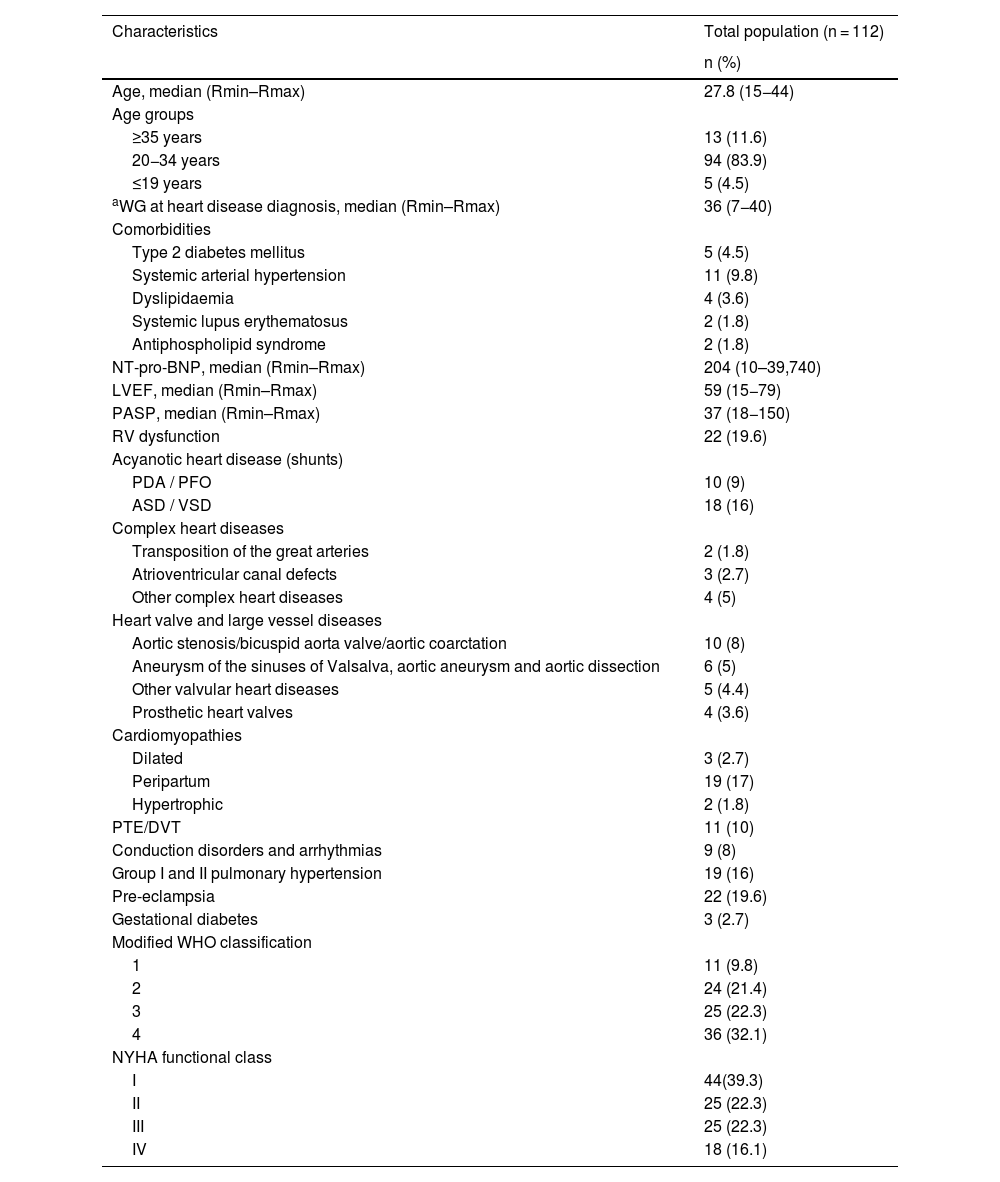

ResultsBaseline population characteristicsThe study included 112 patients whose baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Median age was 28 years with a minimum of 15 and a maximum of 44 years. The first cardiovascular assessment occurred at 30 weeks’ gestation, on average. A total of 36 patients (32%) were classified as class IV in the modified WHO scale and 25 patients (22.3%) as class III. Less than 10% of the population received preconception counselling.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 112 patients with congenital or acquired heart disease during pregnancy and postpartum.

| Characteristics | Total population (n = 112) |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Age, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 27.8 (15−44) |

| Age groups | |

| ≥35 years | 13 (11.6) |

| 20−34 years | 94 (83.9) |

| ≤19 years | 5 (4.5) |

| aWG at heart disease diagnosis, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 36 (7−40) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 5 (4.5) |

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 11 (9.8) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 4 (3.6) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2 (1.8) |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 2 (1.8) |

| NT-pro-BNP, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 204 (10–39,740) |

| LVEF, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 59 (15−79) |

| PASP, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 37 (18−150) |

| RV dysfunction | 22 (19.6) |

| Acyanotic heart disease (shunts) | |

| PDA / PFO | 10 (9) |

| ASD / VSD | 18 (16) |

| Complex heart diseases | |

| Transposition of the great arteries | 2 (1.8) |

| Atrioventricular canal defects | 3 (2.7) |

| Other complex heart diseases | 4 (5) |

| Heart valve and large vessel diseases | |

| Aortic stenosis/bicuspid aorta valve/aortic coarctation | 10 (8) |

| Aneurysm of the sinuses of Valsalva, aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection | 6 (5) |

| Other valvular heart diseases | 5 (4.4) |

| Prosthetic heart valves | 4 (3.6) |

| Cardiomyopathies | |

| Dilated | 3 (2.7) |

| Peripartum | 19 (17) |

| Hypertrophic | 2 (1.8) |

| PTE/DVT | 11 (10) |

| Conduction disorders and arrhythmias | 9 (8) |

| Group I and II pulmonary hypertension | 19 (16) |

| Pre-eclampsia | 22 (19.6) |

| Gestational diabetes | 3 (2.7) |

| Modified WHO classification | |

| 1 | 11 (9.8) |

| 2 | 24 (21.4) |

| 3 | 25 (22.3) |

| 4 | 36 (32.1) |

| NYHA functional class | |

| I | 44(39.3) |

| II | 25 (22.3) |

| III | 25 (22.3) |

| IV | 18 (16.1) |

ASD: atrial septal defect; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PASP: pulmonary artery systolic pressure; PDA: patent ductus arteriosus; PFO: patent foramen ovale; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism; Rmax: maximum range; Rmin: minimum range; RV: right ventricle; VSD: ventricular septal defect; WG: weeks gestation; WHO: World Health Organization.

The most common diagnosis was acyanotic heart disease (shunts) with 28 (25%), of which the most common were ASD and VSD with 18 (16%), followed by peripartum cardiomyopathy with 19 (17%). Average LVEF was 59%, varying between 15% and 79%. In terms of obstetrics and gynaecology history, 69 patients (61%) had undergone one or two caesareans, 81 patients (72%) had experienced at least one miscarriage, and 63 patients (56%) between two and four pregnancies.

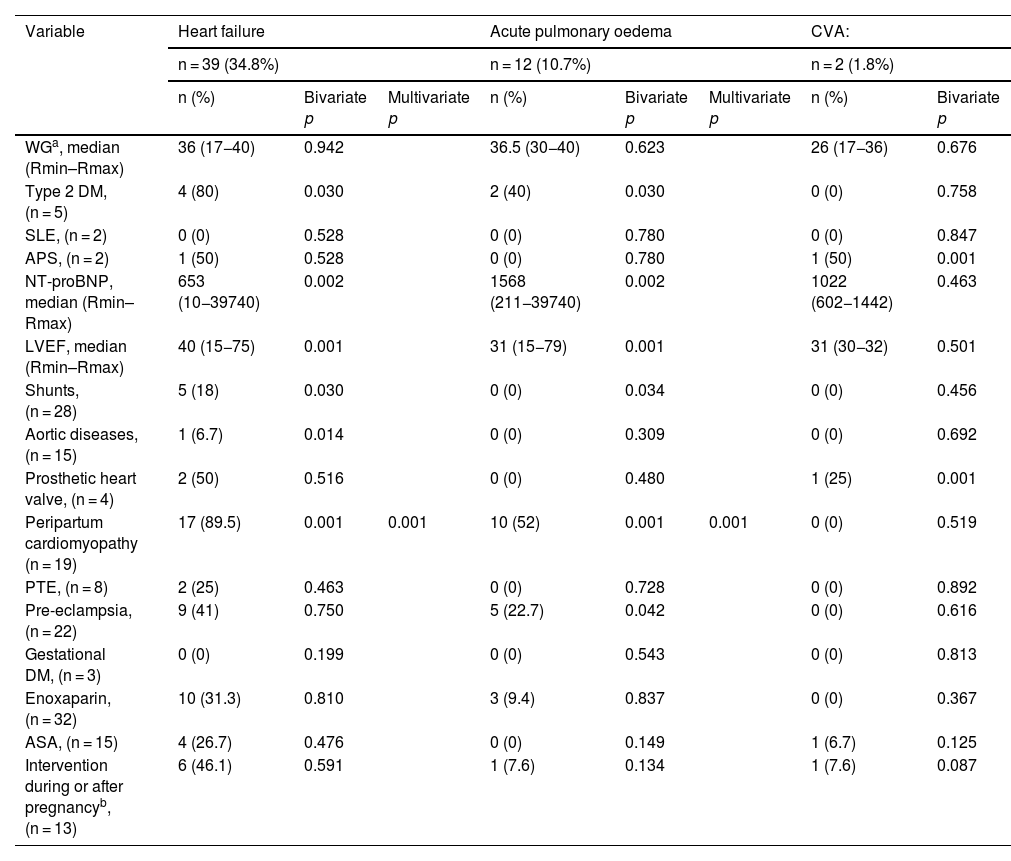

Cardiovascular, obstetric, and perinatal adverse eventsThe most common cardiovascular adverse event was heart failure with 39 (34.8%) followed by acute pulmonary oedema with 12 (10.7%), as shown in Table 2.

Cardiovascular adverse events during pregnancy and postpartum in relation to the clinical characteristics of 112 patients with congenital or acquired heart disease.

| Variable | Heart failure | Acute pulmonary oedema | CVA: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 39 (34.8%) | n = 12 (10.7%) | n = 2 (1.8%) | ||||||

| n (%) | Bivariate p | Multivariate p | n (%) | Bivariate p | Multivariate p | n (%) | Bivariate p | |

| WGa, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 36 (17−40) | 0.942 | 36.5 (30−40) | 0.623 | 26 (17−36) | 0.676 | ||

| Type 2 DM, (n = 5) | 4 (80) | 0.030 | 2 (40) | 0.030 | 0 (0) | 0.758 | ||

| SLE, (n = 2) | 0 (0) | 0.528 | 0 (0) | 0.780 | 0 (0) | 0.847 | ||

| APS, (n = 2) | 1 (50) | 0.528 | 0 (0) | 0.780 | 1 (50) | 0.001 | ||

| NT-proBNP, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 653 (10−39740) | 0.002 | 1568 (211−39740) | 0.002 | 1022 (602−1442) | 0.463 | ||

| LVEF, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 40 (15−75) | 0.001 | 31 (15−79) | 0.001 | 31 (30−32) | 0.501 | ||

| Shunts, (n = 28) | 5 (18) | 0.030 | 0 (0) | 0.034 | 0 (0) | 0.456 | ||

| Aortic diseases, (n = 15) | 1 (6.7) | 0.014 | 0 (0) | 0.309 | 0 (0) | 0.692 | ||

| Prosthetic heart valve, (n = 4) | 2 (50) | 0.516 | 0 (0) | 0.480 | 1 (25) | 0.001 | ||

| Peripartum cardiomyopathy (n = 19) | 17 (89.5) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 10 (52) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0 (0) | 0.519 |

| PTE, (n = 8) | 2 (25) | 0.463 | 0 (0) | 0.728 | 0 (0) | 0.892 | ||

| Pre-eclampsia, (n = 22) | 9 (41) | 0.750 | 5 (22.7) | 0.042 | 0 (0) | 0.616 | ||

| Gestational DM, (n = 3) | 0 (0) | 0.199 | 0 (0) | 0.543 | 0 (0) | 0.813 | ||

| Enoxaparin, (n = 32) | 10 (31.3) | 0.810 | 3 (9.4) | 0.837 | 0 (0) | 0.367 | ||

| ASA, (n = 15) | 4 (26.7) | 0.476 | 0 (0) | 0.149 | 1 (6.7) | 0.125 | ||

| Intervention during or after pregnancyb, (n = 13) | 6 (46.1) | 0.591 | 1 (7.6) | 0.134 | 1 (7.6) | 0.087 | ||

APS: Antiphospholipid syndrome; ASA: Acetylsalicylic acid; CVA: cerebral vascular accident; DM: Diabetes mellitus; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide; Rmax: Maximum range; Rmin: Minimum range; SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus; TEP: Pulmonary thromboembolism; WG: Weeks gestation.

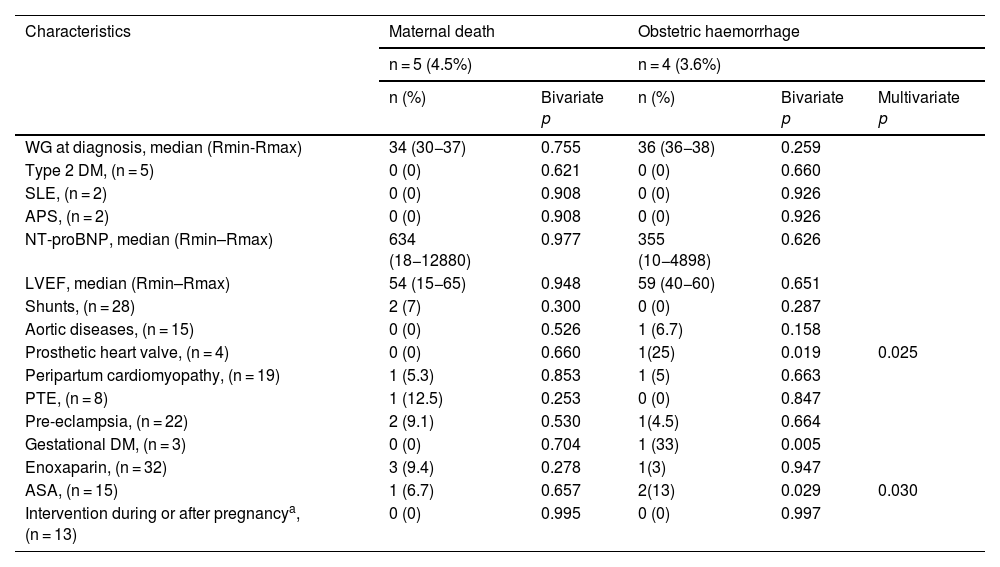

The frequency of maternal mortality at our centre was 5 patients (4.5%), secondary to PTE in 1 (0.9%), peripartum cardiomyopathy in 1 (0.9%), and pre-eclampsia and presence of shunts in 3 (2.7%), as shown in Table 3.

Obstetric adverse events during pregnancy and postpartum in relation to the clinical characteristics of 112 patients with congenital or acquired heart disease.

| Characteristics | Maternal death | Obstetric haemorrhage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 5 (4.5%) | n = 4 (3.6%) | ||||

| n (%) | Bivariate p | n (%) | Bivariate p | Multivariate p | |

| WG at diagnosis, median (Rmin-Rmax) | 34 (30−37) | 0.755 | 36 (36−38) | 0.259 | |

| Type 2 DM, (n = 5) | 0 (0) | 0.621 | 0 (0) | 0.660 | |

| SLE, (n = 2) | 0 (0) | 0.908 | 0 (0) | 0.926 | |

| APS, (n = 2) | 0 (0) | 0.908 | 0 (0) | 0.926 | |

| NT-proBNP, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 634 (18−12880) | 0.977 | 355 (10−4898) | 0.626 | |

| LVEF, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 54 (15−65) | 0.948 | 59 (40−60) | 0.651 | |

| Shunts, (n = 28) | 2 (7) | 0.300 | 0 (0) | 0.287 | |

| Aortic diseases, (n = 15) | 0 (0) | 0.526 | 1 (6.7) | 0.158 | |

| Prosthetic heart valve, (n = 4) | 0 (0) | 0.660 | 1(25) | 0.019 | 0.025 |

| Peripartum cardiomyopathy, (n = 19) | 1 (5.3) | 0.853 | 1 (5) | 0.663 | |

| PTE, (n = 8) | 1 (12.5) | 0.253 | 0 (0) | 0.847 | |

| Pre-eclampsia, (n = 22) | 2 (9.1) | 0.530 | 1(4.5) | 0.664 | |

| Gestational DM, (n = 3) | 0 (0) | 0.704 | 1 (33) | 0.005 | |

| Enoxaparin, (n = 32) | 3 (9.4) | 0.278 | 1(3) | 0.947 | |

| ASA, (n = 15) | 1 (6.7) | 0.657 | 2(13) | 0.029 | 0.030 |

| Intervention during or after pregnancya, (n = 13) | 0 (0) | 0.995 | 0 (0) | 0.997 | |

APS: antiphospholipid syndrome; ASA: acetylsalicylic acid; DM: diabetes mellitus; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide; Rmax: maximum range; Rmin: minimum range; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; TEP: pulmonary thromboembolism; WG: Weeks’ gestation.

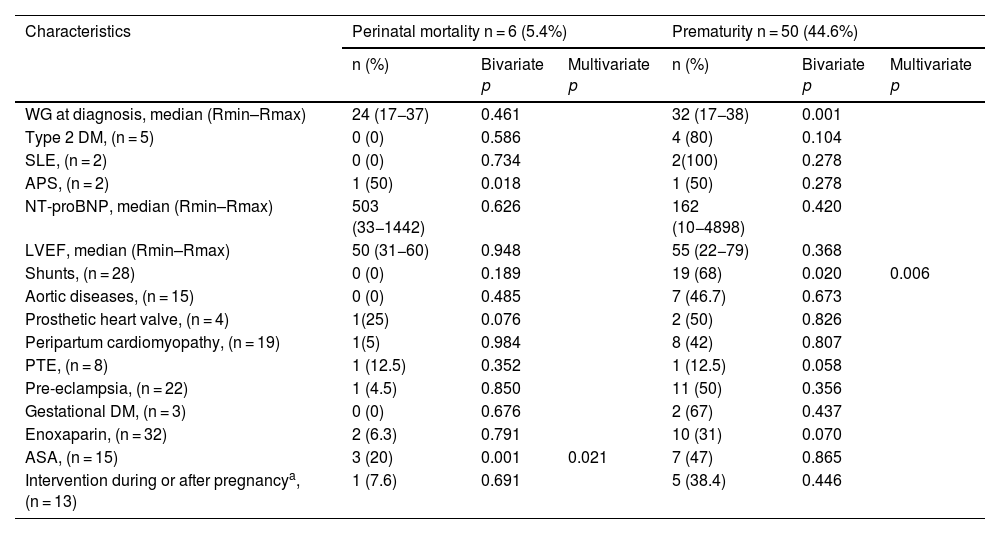

On the other hand, the most common obstetric and perinatal events were obstetric haemorrhage in 4 (3.6%), as shown in Table 3, and prematurity in 50 (44.5%), with this latter being associated with the presence of shunts in the mother in 19 cases (17%), Table 4. Late preterm birth was most common, with 24 (21.4%), followed by moderate preterm, with 13 (11.6%), and very preterm birth, with 12 (10.7%).

Perinatal adverse events during pregnancy and postpartum in relation to the clinical characteristics of 112 patients with congenital or acquired heart disease.

| Characteristics | Perinatal mortality n = 6 (5.4%) | Prematurity n = 50 (44.6%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Bivariate p | Multivariate p | n (%) | Bivariate p | Multivariate p | |

| WG at diagnosis, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 24 (17−37) | 0.461 | 32 (17−38) | 0.001 | ||

| Type 2 DM, (n = 5) | 0 (0) | 0.586 | 4 (80) | 0.104 | ||

| SLE, (n = 2) | 0 (0) | 0.734 | 2(100) | 0.278 | ||

| APS, (n = 2) | 1 (50) | 0.018 | 1 (50) | 0.278 | ||

| NT-proBNP, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 503 (33−1442) | 0.626 | 162 (10−4898) | 0.420 | ||

| LVEF, median (Rmin–Rmax) | 50 (31−60) | 0.948 | 55 (22−79) | 0.368 | ||

| Shunts, (n = 28) | 0 (0) | 0.189 | 19 (68) | 0.020 | 0.006 | |

| Aortic diseases, (n = 15) | 0 (0) | 0.485 | 7 (46.7) | 0.673 | ||

| Prosthetic heart valve, (n = 4) | 1(25) | 0.076 | 2 (50) | 0.826 | ||

| Peripartum cardiomyopathy, (n = 19) | 1(5) | 0.984 | 8 (42) | 0.807 | ||

| PTE, (n = 8) | 1 (12.5) | 0.352 | 1 (12.5) | 0.058 | ||

| Pre-eclampsia, (n = 22) | 1 (4.5) | 0.850 | 11 (50) | 0.356 | ||

| Gestational DM, (n = 3) | 0 (0) | 0.676 | 2 (67) | 0.437 | ||

| Enoxaparin, (n = 32) | 2 (6.3) | 0.791 | 10 (31) | 0.070 | ||

| ASA, (n = 15) | 3 (20) | 0.001 | 0.021 | 7 (47) | 0.865 | |

| Intervention during or after pregnancya, (n = 13) | 1 (7.6) | 0.691 | 5 (38.4) | 0.446 | ||

APS: antiphospholipid syndrome; ASA: acetylsalicylic acid; DM: diabetes mellitus; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide; Rmax: maximum range; Rmin: minimum range; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; TEP: pulmonary thromboembolism; WG: weeks gestation.

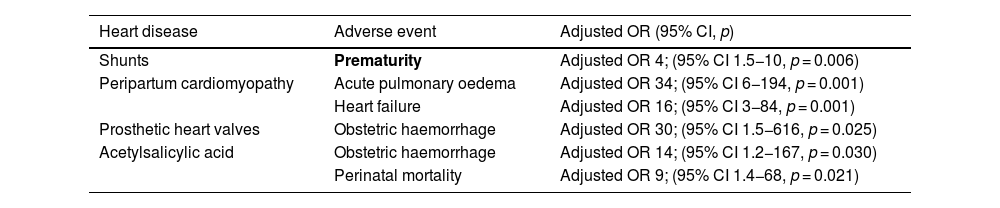

Significant associations were found with the following adverse events: prosthetic heart valves with obstetric haemorrhage (adjusted OR 30; 95% CI: 1.5−616, p = 0.025); peripartum cardiomyopathy with acute pulmonary oedema (adjusted OR 34; 95% CI: 6−194, p = 0.001) and heart failure (adjusted OR 16; 95% CI: 3−84, p = 0.001), and shunt diagnosis with prematurity (adjusted OR 4; 95% CI: 1.5−10, p = 0.006), as listed in Table 5.

Association between congenital and/or acquired heart disease and implemented treatment with adverse events.

| Heart disease | Adverse event | Adjusted OR (95% CI, p) |

|---|---|---|

| Shunts | Prematurity | Adjusted OR 4; (95% CI 1.5−10, p = 0.006) |

| Peripartum cardiomyopathy | Acute pulmonary oedema | Adjusted OR 34; (95% CI 6−194, p = 0.001) |

| Heart failure | Adjusted OR 16; (95% CI 3−84, p = 0.001) | |

| Prosthetic heart valves | Obstetric haemorrhage | Adjusted OR 30; (95% CI 1.5−616, p = 0.025) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | Obstetric haemorrhage | Adjusted OR 14; (95% CI 1.2−167, p = 0.030) |

| Perinatal mortality | Adjusted OR 9; (95% CI 1.4−68, p = 0.021) |

An antiphospholipid syndrome diagnosis had significant differences for the outcome of CVA (p = 0.001) and perinatal mortality (p = 0.018) in the bivariate analysis but not the multivariate analysis. Likewise, the values for NT-proBNP>1000 (72%, p = 0.002), LVEF<54% (55%, p = 0.001) presented statistically significant differences for the outcome of heart failure and acute pulmonary oedema NT-proBNP>1000 (30%, p = 0.002), LVEF<54% (23%, p = 0.001).

Treatment implementedThe interventional, medical, or surgical treatments implemented during or after pregnancy and their associations with the adverse events assessed are detailed in the last rows of Tables 2,3, and Table 4.

Enoxaparin was the most administered medication, in 32 cases (28.6%), followed by acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) in 15 (13.4%).

The use of acetylsalicylic acid during or after pregnancy had a higher risk for obstetric haemorrhage, with an adjusted OR of 14 (95% CI: 1.2−167, p = 0.030), and for perinatal mortality with adjusted OR 9 (95% CI: 1.4−68, p = 0.021) as described in Table 5.

Only 9.8% of the population underwent heart disease intervention prior to pregnancy. A total of 11.7% underwent intervention during or after pregnancy. The most common procedure was shunt closure, with 5 cases (4.5%).

Pregnancy mainly resolved at week 35.5 and occurred via caesarean section, with 110 cases (98.2%).

DiscussionOur study reported a 4.5% mortality rate. This piece of data stands out given that a 2-year registry from the United Kingdom reported a maternal mortality rate of 11.39 per 100,000 pregnancies, with heart disease being the main cause of death.15 On the other hand, in a study by Farr et al. including 238 pregnant women admitted to the intensive care unit during the second trimester and the 6 weeks after birth, the mortality rate was 5%.14

Both the United Kingdom registry15 and the CMACE study (Center for Maternal and Child Enquiries)16 reported that the most common heart diseases were sudden death syndrome, peripartum cardiomyopathy, aortic dissection, and acute myocardial infarction. We agree with these authors regarding the significance of peripartum cardiomyopathy, as it was the second most common diagnosis in our population.

A retrospective study by Siu et al. (2001), which included 562 patients, reported congenital heart disease as the most common heart disease during pregnancy (74%), which is also in line with our study.

The variables associated with mortality in pregnant patients with pre-existing heart disease are: pulmonary hypertension, severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction, Marfan syndrome with aortic root dilation greater than 45 mm, symptomatic aortic stenosis, and a history of prosthetic heart valve.17 We found that pulmonary hypertension and high risk aortopathies were not associated with mortality; however, LVEF decline did present significant differences with respect to the outcome of decompensated heart failure and acute pulmonary oedema.

In addition to LVEF, our study suggests that NT-proBNP is useful for predicting decompensated heart failure and acute pulmonary oedema. In this respect, the study by Ker and Soma-Pillay also suggested that NT-proBNP can be used as a screening for subclinical systolic dysfunction.18

Large registries like CARPREG, CARPREG II, ZAHARA, ROPAC, BACH, etc., have mainly searched for associations with maternal mortality17 and did not assess other significant outcomes such as heart failure, obstetric haemorrhage, acute pulmonary oedema, or CVA, which contrasts with our findings.

Some 32% of our patients were found to be in the high risk category of the modified WHO classification (class IV), however 39% of our population pertained to NYHA functional class I, unlike other prospective studies, in which the modified WHO classification IV only represented 23% of their population.19 This is noteworthy, since pregnancy is contraindicated in said classication.20

One of the studies to assess outcomes other than maternal mortality is that of Lu CW et al. (2015) which, like our study, reported heart failure, obstetric haemorrhage, and prematurity as the most common cardiovascular, obstetric, and perinatal adverse events.21

In the bivariate and multivariate analysis, heart valve prosthesis and peripartum cardiomyopathy diagnoses showed statistical significance with the adverse events assessed (acute oedema, heart failure, and obstetric haemorrhage); however, a broad 95% CI was calculated for all of them.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy involves a 44% risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies with a mortality rate of 19%.22 However, in this study, no peripartum cardiomyopathy recurrence was observed. Nevertheless, a higher frequency of heart failure and acute pulmonary oedema was observed.

A history of mechanical heart valves involves a risk of thrombosis, particularly with mechanical mitral valves and older generations of valves,23 though it also entails a risk of bleeding as found in our analysis.

On the other hand, the literature has reported that DVT/PE is one of the leading causes of direct maternal death (113 deaths per 100,000 pregnancies).24 According to our results, DVT/PE was present in 10% of cases and only one patient suffered a fatal outcome.

With regard to antiphospholipid syndrome diagnosis, it presented statistical significance with CVA and perinatal death; this is in line with the retrospective study from Malhamé (2022), in which systemic lupus erythematosus diagnosis carried a 2.5-fold higher risk of maternal mortality (95% CI 1.31–4.78).25

Regarding pre-eclampsia diagnoses, Rutherford et al. (2012) published that the rate of pre-eclampsia in pregnancies in the United States is between 5% and 8%,6 which is twice that observed in our study.

Regarding perinatal outcomes, Siu et al. (2001) reported foetal/neonatal mortality rates of 2% and prematurity rates of 10%, with those of our study being higher.

A study by Drenthen et al. found that the risk of death in children born to mothers with heart disease increased fourfold11; our findings contribute to explaining those results since a nine-fold increased adjusted risk of perinatal mortality was calculated in mothers with heart disease treated with acetylsalicylic acid. Nevertheless, additional studies are needed to establish a causal relationship.

The risk of passing on congenital heart disease to offspring is 4%.26 Nevertheless, we found that only one neonate, or 0.89%, presented congenital heart disease (perimembranous VSD).

It is noteworthy that almost 100% of the patients in this study underwent caesarean sections. The international guidelines suggest caesarean sections for patients taking oral anticoagulants at the time of birth with severe aortic disease, worsening heart failure, and severe pulmonary hypertension.27 In fact, the ROPAC study showed that elective caesareans do not provide any maternal benefit and result in premature birth and low birth weight.28

ConclusionsThe most common cardiovascular, obstetric, and perinatal adverse events associated with heart disease during pregnancy and postpartum are heart failure, acute pulmonary oedema, obstetric haemorrhage, and prematurity.

Pregnant patients with antiphospholipid syndrome may benefit from closer monitoring due to the risk of CVA and perinatal death. Heart valve prosthesis and peripartum cardiomyopathy diagnoses entail a higher risk of adverse events. Left ventricular ejection fraction and NT-proBNP may be useful predictors of heart failure and acute pulmonary oedema, which could optimise risk stratification in pregnancy with heart disease.

The use of acetylsalicylic acid is not harmless for the mother, nor is the product. Meanwhile, other medical, interventional, or surgical treatments present no association with the adverse events studied. Serious complications can occur for heart disease patients during pregnancy and postpartum, so preconception assessments and cardiac monitoring are of vital importance in women of reproductive age.

Conflicts of interestThe authors of this article declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

FundingThis research did not receive any resources, monetary or in kind, from public or private finance centres nor from not-for-profit organisations.