Despite currently available treatments, risk of death and hospitalizations in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) remains high. The pathophysiology of HFrEF includes neurohormonal activation characterized by stimulation of deleterious pathways (i.e., sympathetic nervous and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems) and suppression of protective pathways such as nitric oxide-dependent pathways. Inhibition or stimulation of some, but not all, of these pathways is insufficient. In HFrEF, there is reduced nitric oxide, soluble guanylate cyclase, and cGMP activity, leading to deleterious effects in the myocardial, vascular, and renal systems. Vericiguat is able to stimulate the activity of this protective pathway. The VICTORIA study demonstrated that the addition of vericiguat to optimal medical treatment in patients with HFrEF and recent decompensation significantly reduced the incidence of the primary endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization, with a number needed to treat of 24 patients and excellent tolerability.

A pesar de los tratamientos actuales, el riesgo de muerte y hospitalizaciones en pacientes con insuficiencia cardíaca con fracción de eyección reducida (IC-FEr) sigue siendo elevado. La fisiopatología de la IC-FEr incluye activación neurohormonal caracterizada por la estimulación de las vías deletéreas (sistemas simpático y renina-angiotensina-aldosterona) y la supresión de las vías protectoras como las dependientes del óxido nítrico. La inhibición o estimulación de algunas de estas vías, pero no de todas, es insuficiente. En la IC-FEr existe una menor actividad de óxido nítrico, guanilato ciclasa soluble y GMPc que provoca efectos deletéreos a nivel miocárdico, vascular y renal. Vericiguat estimula la actividad de esta vía protectora. El estudio VICTORIA demostró, en pacientes con IC-FEr y descompensación reciente, que la adición de vericiguat al tratamiento médico óptimo reducía de forma significativa la incidencia del objetivo primario muerte cardiovascular u hospitalización por IC, con un número de 24 pacientes que es necesario tratar, y una excelente tolerabilidad.

Heart failure (HF) is a common disease with an estimated prevalence of around 2% of the adult population in developed countries, though this is expected to increase in coming years, mainly due to population aging.1–5

HF is associated with high morbidity and mortality6–9 and hospitalization due to HF is a predictive factor of mortality.1,10 HF has a marked negative impact on patients’ quality of life.11 The costs associated with HF are very high, with hospitalization being the main component.12,13 Fortunately, treatment optimization is associated with a reduction in healthcare costs.14

HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is a progressive disease which entails a gradual deterioration in heart function over time interspersed with periods of acute decompensation, which worsen a patient’s prognosis even further.15,16 Approximately one in six patients with HFrEF will have an episode of worsening in the 18 months following the HF diagnosis.16 Likewise, chronic worsening of HF accounts for 80% of hospitalizations due to HF.17 In addition to worsening the prognosis, each time the patient is admitted, the hospitalization tends to be more severe and prolonged and the time between episodes of decompensation is less.18,19

As a result, it is necessary to optimize treatment to attempt to decrease the burden of HF.16,20–22 However, in order to do so, it is essential to understand that the etiopathogenesis of HF is a complex process in which numerous neurohormonal systems play a role. Therefore, therapeutic management must be focused on the treatment of the various neurohormonal systems in a comprehensive manner (Table 1).23–29

Etiopathogenesis of heart failure and potential treatments.

| Systems involved | Mechanism involved in the HF | Potential drug(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system | Activation | Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors: ACE inhibitors, ARBs, aldosterone antagonists |

| Sympathetic nervous system | Activation | Beta-blockers |

| Natriuretic peptides | Inhibition | Neprilysin inhibitors: natriuretic peptide activation |

| SGLT-2 | Activationa | SGLT-2 inhibitorsa |

| Guanylate cyclase | Inhibition | Guanylate cyclase activation: vericiguat |

ARB: angiotensin-2 receptor blockers; HF: heart failure; ACE inhibitors: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; SGLT-2: sodium/glucose cotransporter 2.

Adapted from Triposkiadis et al.,23 McDonagh et al.,24 Maddox et al.,25 McDonald et al.,26 Matsumura and Sugiura,27 Armstrong et al.,28 and Nightingale.29.

The mechanisms by which SGLT-2 inhibitors provide a cardioprotective mechanism are not well known. They include hemodynamic factors, sympathetic stimulation control, fibrosis and cardiac remodeling inhibition, cardiac output improvements, cytosolic sodium and calcium concentration modulation, and changes in adipokine levels.

A recent study which analyzed the combined outcomes of various clinical trials found that treatment with sacubitril/valsartan, beta blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and sodium–glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors (SGLT-2) was associated with significant reductions in cardiovascular events compared to the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin-2 receptor blockers plus beta blockers.30

Consequently, it is necessary to start treatment early with drugs that have been demonstrated to improve prognosis and thus decrease cardiovascular events in patients with HF.31 Unfortunately, a substantial percentage of patients with HF are not taking the combination of recommended treatments; this is associated with increased risk of presenting with complications.32

Clinical practice guidelines for HF have traditionally had a vertical treatment approach, adding or modifying treatment if symptoms persist.33 However, this approach entails a delay in treatment optimization which could potentially lead to a worse long-term prognosis.34,35

New recommendations have changed this focus, moving from a sequential, “vertical” treatment approach to a more “cross-cutting” approach with the specific aim of the patient obtaining the maximum benefit from the beginning.24–26 The latest European HF guidelines from 2021 recommend the use of sacubitril/valsartan or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and SGLT-2 inhibitors as first-line therapy and vericiguat as second-line therapy for symptomatic patients with HFrEF.

European HF guidelines indicate that treatment with vericiguat should be considered in symptomatic patients who present with worsening of HF despite first-line treatment to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death or hospitalization due to HF (recommendation IIb, level of evidence B).24 The European Medicines Agency has approved vericiguat for the treatment of symptomatic chronic HF in adult patients with HFrEF who are stable after a recent episode of decompensation which required intravenous diuretic treatment.36 However, it is important to note that despite first-line treatment, the residual risk of events remains high.37

Therefore, the use of new treatments such as vericiguat, which act on the complementary pathophysiological pathways, continues to be necessary in order to help decrease the burden of disease the HF entails.

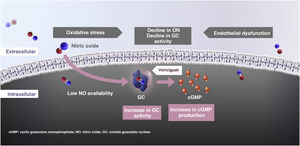

Vericiguat: mechanism of action and pharmacokinetic parametersIn HF, there is a change in nitric oxide synthesis as well as a decrease in the activity of its receptor, soluble guanylate cyclase (GC), which in turn causes a cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) deficiency. The cGMP deficiency causes deterioration in myocardial, vascular, and renal function. None of the current HF treatments (beta blockers, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, SGLT-2 inhibitors) act through this pathway.

Vericiguat is an oral drug that directly stimulates GC, which increases the availability of intracellular cGMP and thus produces beneficial effects, reestablishing the relative deficiency of the nitric oxide-GC-cGMP signaling pathway through direct stimulation of GC in an independent, synergetic manner with nitric oxide.

The increase in cGMP translates into a reduction in left ventricular remodeling, an improvement in myocardial and vascular function, and a decrease in fibrosis and inflammation (Fig. 1).36,38–45 In consequence, unlike other drugs that inhibit certain deleterious pathways that are activated, such as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system or the sympathetic nervous system, vericiguat and sacubitril stimulate the protective pathways (nitric oxide-GC-GMP system and natriuretic peptides, respectively) (Table 1).23–29

In regard to pharmacokinetics, the absolute bioavailability of vericiguat is high when it is taken with food (93%) and thus taking it with food is recommended. Its plasma protein binding, mainly with albumin, is approximately 98%. With respect to metabolism, glucuronidation through UGT1A9 and UGT1A1 is the main pathway of biotransformation, whereas the metabolism mediated by the cytochrome P450 is small (<5%). Therefore, the risk of pharmacokinetic interactions with other drugs is low. Nevertheless, concomitant use of vericiguat and other GC stimulators such as riociguat is contraindicated. The mean half-life in healthy subjects is about 20 h and is up to 30 h in patients with HF. Approximately 53% is excreted in urine and 45% in feces. It is not necessary to adjust the dose based on age, sex, race, body weight, or baseline natriuretic peptide levels. It is also not necessary to adjust the dose in subjects with a glomerular filtration rate ≥15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or with mild or moderate liver failure. The use of vericiguat in subjects with more advanced kidney disease or severe liver failure has not been studied.36,46–50

Clinical development of vericiguatFour main clinical trials are of note in the clinical development of vericiguat: two phase II studies (SOCRATES (SOluble guanylate Cyclase stimulatoR in heArT failurE Study)-REDUCED and SOCRATES-PRESERVED) and two phase III studies (VICTORIA (Vericiguat Global Study in Subjects with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction) and VITALITY (Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of the Oral sGC Stimulator Vericiguat to Improve Physical Functioning in Daily Living Activities of Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction)).

The phase II SOCRATES program comprises two multicenter, parallel-group, placebo controlled clinical trials: the SOCRATES-REDUCED study in patients with LVEF < 45% and the SOCRATES-PRESERVED study in patients with LVEF ≥ 45%. These trials analyzed the pharmacodynamic effects, pharmacokinetic effects, safety, and tolerability of four different vericiguat doses during 12 weeks in patients included upon discharge or four weeks after a HF hospitalization. The primary outcome variable in the SOCRATES-REDUCED study was the change in N-terminal brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels. The primary outcome variable in the SOCRATES-PRESERVED study was the change in NT-proBNP levels and left atrial volume after 12 weeks of treatment.51

A total of 456 patients were included in the SOCRATES-REDUCED study: 92 in the placebo group and 91 in each vericiguat group (1.25 mg; 2.5 mg; 5 mg; and 10 mg). Although overall there were no significant differences with respect to changes in the natriuretic peptide levels with vericiguat compared to the placebo, a dose-response relationship with vericiguat was observed (greater doses led to a greater reduction; p < 0.02). Although this study did not have enough power to evaluate clinical events, the rates of mortality and hospitalization due to HF were numerically lower with vericiguat than with the placebo (11% and 12.1% with vericiguat 10 mg and 5 mg, respectively, versus 19.6% in the placebo group). In addition, tolerance of vericiguat was good.52

In the SOCRATES-PRESERVED study, though treatment with vericiguat was not associated with significant changes in NT-proBNP level or left atrial volume, an improvement in the quality of life and health status of patients treated with vericiguat was observed, in addition to good tolerance.53,54

The VICTORIA study was a phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted with the aim of evaluating the effects of vericiguat in patients with chronic symptomatic HF after an episode of HF worsening.

It included patients with HFrEF (LVEF < 45%), New York Heart Association functional class II-IV, high natriuretic peptide levels (brain natriuretic peptides (BNP) ≥ 300 pg/mL or NT-proBNP ≥1000 pg/mL if sinus rhythm; BNP ≥ 500 pg/mL or NT-proBNP ≥1600 pg/mL if atrial fibrillation), estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥15 mL/min/1.73 m2, and hospitalization due to HF in the previous six months or intravenous (IV) diuretic treatment for HF in the previous three months.

Patients were randomized to receive vericiguat (initial dose 2.5 mg once per day, target dose of 10 mg once per day) or a placebo in addition to standard HF therapy. The study’s primary outcome variable was the composite of cardiovascular death or first hospitalization due to HF.55 Patients’ baseline characteristics are shown in Table 2. In 89.2% of cases, the target dose of vericiguat was reached.55

VICTORIA study baseline characteristics.

| Vericiguat (n = 2526) | Placebo (n = 2524) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 67.5 ± 12.2 | 67.2 ± 12.2 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 1921 (76.0) | 1921 (76.1) |

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | ||

| I | 0 | 2/2523 (0.1) |

| II | 1478/2523 (58.6) | 1497/2523 (59.3) |

| III | 1010/2523 (40.0) | 993/2523 (39.4) |

| IV | 35/2523 (1.4) | 31/2523 (1.2) |

| LVEF, % | 29.0 ± 8.26 | 28.8 ± 8.34 |

| Index event, n (%) | ||

| HF hospitalization at 3 months | 1673 (66.2) | 1705 (67.6) |

| HF hospitalization at 3−6 months | 454 (18.0) | 417 (16.5) |

| IV diuretics due to HF (without hospitalization) at 3 months | 399 (15.8) | 402 (15.9) |

| HF treatment, n (%) | ||

| Beta-blockers | 2349 (93.2) | 2342 (93.0) |

| ACEI/ARB | 1847 (73.3) | 1853 (73.6) |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 1747 (69.3) | 1798 (71.4) |

| Sacubitril/valsartan | 360 (14.3) | 371 (14.7) |

| ICD | 696 (27.6) | 703 (27.9) |

| CRT | 370 (14.7) | 369 (14.6) |

ARB: angiotensin-2 receptor blockers; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; HF: heart failure; ACE inhibitors: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; NYHA: New York Heart Association; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy; IV: intravenous.

Adapted from Armstrong et al.55.

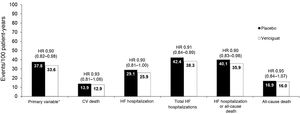

After a median follow-up time of 10.8 months, treatment with vericiguat was associated with a significant reduction in the primary outcome variable of 10% (hazard ratio (HR) 0.90; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 0.82−0.98; p = 0.02). In addition, significant reductions in total hospitalizations due to HF and the composite variable of hospitalization due to HF or all-cause death were observed (Fig. 2). The results regarding the primary outcome variable were consistent in the different subgroups of patients analyzed (Table 3).55

Principal events in the VICTORIA study.

CV: cardiovascular; HR: hazard ratio; HF: heart failure.

*Cardiovascular death or first hospitalization due to heart failure.

Adapted from Armstrong et al.55

Subgroup analysis of the primary outcome of the VICTORIA study.

| Characteristic | Number of events (vericiguat/placebo) | HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 704/762 | 0.90 | 0.81–1.00 |

| Female | 193/210 | 0.88 | 0.73–1.08 |

| Age (years) | |||

| <65 | 290/348 | 0.81 | 0.70–0.95 |

| ≥65 | 607/624 | 0.94 | 0.84–1.06 |

| Age (years) | |||

| <75 | 579/669 | 0.84 | 0.75–0.94 |

| ≥75 | 318/303 | 1.04 | 0.88–1.21 |

| Index event | |||

| IV diuretics < 3 months ago | 96/120 | 0.78 | 0.60–1.02 |

| Hospitalization <3 months ago | 660/701 | 0.93 | 0.84–1.04 |

| Hospitalization 3–6 months ago | 141/151 | 0.85 | 0.67–1.07 |

| Baseline glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2) | |||

| ≤30 | 143/128 | 1.06 | 0.83–1.34 |

| >30 to ≤60 | 392/445 | 0.84 | 0.73–0.96 |

| >60 | 346/372 | 0.92 | 0.80–1.07 |

| Baseline NYHA functional class | |||

| Class I/II | 445/484 | 0.91 | 0.80–1.04 |

| Class III/IV | 451/487 | 0.87 | 0.77–0.99 |

| Baseline use of sacubitril/valsartan | |||

| Yes | 134/153 | 0.88 | 0.70–1.11 |

| No | 760/818 | 0.90 | 0.81–0.99 |

| Baseline NT-proBNP by quartiles (pg/mL) | |||

| Q1 (≤1556) | 128/161 | 0.78 | 0.62–0.99 |

| Q2 (1556–2816) | 165/201 | 0.73 | 0.60–0.90 |

| Q3 (2816–5314) | 213/257 | 0.82 | 0.69–0.99 |

| Q4 (>5314) | 355/302 | 1.16 | 0.99–1.35 |

| Baseline ejection fraction | |||

| <35% | 637/703 | 0.88 | 0.79–0.97 |

| ≥35% | 255/265 | 0.96 | 0.81–1.14 |

| <40% | 773/851 | 0.88 | 0.80–0.97 |

| ≥40% | 119/117 | 1.05 | 0.81–1.36 |

| Overall | 897/972 | 0.90 | 0.82–0.98 |

HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

Adapted from Armstrong et al.55

Although the risk of the primary outcome variable increased the closer the hospitalization due to HF was and decreased in more chronic patients, the benefit of vericiguat was observed in all patients, though there was a tendency of a greater benefit when more time had passed since the hospitalization (p = 0.09).

Likewise, it seems that the benefit of vericiguat in regard to the primary outcome variable and its two separate components was greater in subjects with NT-proBNP ≤8000 pg/mL (86% of the VICTORIA population). The benefit of vericiguat was independent of the treatment for HF that the patient was taking, either when analyzed alone or in combination. In addition, treatment with vericiguat was not associated with a deterioration in renal function and its efficacy and safety were independent of the glomerular filtration rate.28,38,55–58

In regard to risk of side effects, severe adverse events were similar in both groups. Symptomatic hypotension occurred in 9.1% of patients treated with vericiguat and in 7.9% of patients in the placebo group (p = 0.12) and syncope occurred in 4% and 3.5% of patients, respectively (p = 0.30). Systolic blood pressure declined slightly in both treatment arms during the first 16 weeks of the study and then returned to baseline levels. More cases of anemia were described with vericiguat (7.6% and 5.7%, respectively), of which 1.6% and 0.9% were considered to be severe adverse effects.55

The VITALITY study was designed to learn the efficacy and safety of vericiguat on quality of life and exercise tolerance of patients with HF and preserved LVEF. A total of 789 patients with chronic HF, EF ≥ 45%, New York Heart Association functional class II or III, a recent decompensation in the previous six months (hospitalization due to HF or need for IV diuretics for HF without hospitalization), and elevated natriuretic peptides were included.

Patients were randomized to receive vericiguat titered up to 15 mg (n = 264) or 10 mg (n = 263) or a placebo (n = 262). No significant differences were found between the groups on the Kansas City questionnaire physical limitation scores or on the six-minute test after 24 weeks of treatment.59,60

Role of vericiguat in the treatment of patients with heart failureThe 2021 European HF guidelines establish the use of sacubitril-valsartan or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and SGLT-2 inhibitors as first-line treatment for patients with HFrEF. Vericiguat would be the second step of treatment in patients who remained symptomatic, mainly after a recent decompensation.24 These recommendations are fundamentally based on pivotal clinical trials for these drugs.

However, given that at present there are no clinical trials that compare the efficacy of different HF treatments among themselves and only indirect comparisons can be made among studies, it is important to conduct a critical analysis.61,62 Comparing the outcomes of clinical trials only using the HR is clearly insufficient; it requires a comprehensive evaluation of the studies that considers their design, the risk profile of the patients included, the study duration, and the absolute and relative risk reductions.

In this context, and considering patients’ different risk profiles, the absolute differences in annualized risk could provide more relevant information than comparing the HR.61,62 For example, whereas the relative reductions in the PARADIGM HF, DAPA-HF, and EMPEROR-Reduced studies were greater than those obtained in the VICTORIA study, the absolute risk reductions were similar for vericiguat and SGLT-2 inhibitors and greater than those obtained with sacubitril/valsartan. Furthermore, it must be taken into consideration that patients included in the VICTORIA study were at higher risk compared to the rest of contemporaneous HF studies. In fact, the number of patients needed to treat for the primary outcome measure was 24 patients for vericiguat and 37 patients for sacubitril/valsartan (Table 4).55,63–65

Baseline characteristics and principal events of the PARADIGM HF, DAPA-HF, EMPEROR-Reduced, and VICTORIA studies.

| PARADIGM HF (n = 8399)Sacubitril/valsartan | DAPA-HF (n = 4744)Dapagliflozin | EMPEROR-Reduced (n = 3730)Empagliflozin | VICTORIA (n = 5050)Vericiguat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study designs | ||||

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | ≥600 or ≥400 | ≥600 or ≥400 | Varies with LVEF | ≥1000 sinus rhythm ≥1600 atrial fibrillation |

| If HF hospitalization <12 months | If HF hospitalization <12 months | |||

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | ≥30 | ≥30 | ≥20 | ≥15 |

| LVEF, % | ≤35% | ≤40% | ≤40% | <45% |

| Recent HF decompensation | Not required | Not required | Chronic HF ≥ 3 months | HF hospitalizations < 6 months or IV diuretics < 3 months |

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| NT-proBNP (median), pg/mL | 1608 | 1437 | 1906 | 2816 |

| NYHA functional class III or IV, % | 25 | 32 | 25 | 41 |

| HF hospitalization <3 months, % | 19 | 8 | NR | 67 |

| HF hospitalization <6 months, % | 31 | 16 | NA | 84 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 68 | 66 | 62 | 62 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 37 | 41 | 48 | 53 |

| Principal events | ||||

| Primary outcome | First hospitalization due to HF or CV death | Worsening of HF (unscheduled hospitalization/emergency visit that required IV treatment for HF) or CV death | First hospitalization due to HF or CV death | First hospitalization due to HF or CV death |

| Median follow-up (months) | 27 | 18 | 16 | 11 |

| Rate of primary outcome variable events in the control arma | 13.2 | 15.6 | 21.0 | 37.8 |

| Primary outcome variable, HR (95% CI) | 0.80 (0.73–0.87) | 0.74 (0.65–0.85) | 0.75 (0.65–0.86) | 0.90 (0.82–0.98) |

| CV death, HR (95% CI) | 0.80 (0.71–0.89) | 0.82 (0.69–0.98) | 0.92 (0.75–1.12) | 0.93 (0.81–1.06) |

| First hospitalization due to HF, HR (95% CI) | 0.79 (0.71–0.89) | 0.70 (0.59–0.83) | 0.69 (0.59–0.81) | 0.90 (0.81–1.00) |

| Control | Sac/Vals | Control | Dapagliflozin | Control | Empagliflozin | Control | Vericiguat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome variable*a | 13.2 | 10.5 | 15.6 | 11.6 | 21.0 | 15.8 | 37.8 | 33.6 |

| ARR/NNT | 2.7 | 37.0 | 4.0 | 25.0 | 5.2 | 19.2 | 4.2 | 23.8 |

| CV deatha | 7.5 | 6.0 | 7.9 | 6.5 | 8.1 | 7.6 | 13.9 | 12.9 |

| ARR/NNT | 1.5 | 66.7 | 1.4 | 71.4 | 0.6 | 166.7 | 1.0 | 100 |

| First HF hospitalizationa | 7.7 | 6.2 | 9.8 | 6.9 | 15.5 | 10.7 | 29.1 | 25.9 |

| ARR/NNT | 1.6 | 62.5 | 2.9 | 34.5 | 4.8 | 20.8 | 3.2 | 31.2 |

CV: cardiovascular; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR: hazard ratio; HF: heart failure; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; NA: not applicable; NNT: number needed to treat; NR: not reported; NT-proBNP: N-terminal brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA: New York Heart Association; ARR: absolute risk reduction; sac/vals: sacubitril/valsartan.

Table created with data from Armstrong et al.,55 McMurray et al.,63 McMurray et al.,64 and Packer et al.65.

In consequence, it is necessary to go beyond clinical practice guidelines66 and carry out an individualized therapeutic approach, using drugs that have demonstrated clinical benefits based on each patient’s characteristics (blood pressure, heart rate, renal function, serum potassium levels, etc.) and not just the differences among the various clinical trials.67

In regard to the method of use of vericiguat, the initial recommended dose is 2.5 mg of vericiguat once per day, doubling the dose approximately every 2 weeks until the patient reaches the target maintenance dose of 10 mg once per day, based on tolerance. Treatment is associated with a modest reduction in systolic blood pressure compared to a placebo (1−2 mmHg) and monitoring electrolytes is not necessary.

Starting vericiguat is not recommended in patients with systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg. For symptomatic hypotension, reducing/suspending the dose of vericiguat is recommended, according to the case. Significant drug interactions are not expected, though it is recommended not to use phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors concomitantly. Before beginning treatment with vericiguat after an episode of HF decompensation, it is recommended to optimize the volemic/diuretic status, in particular in patients with very high NT-proBNP levels.36

With respect to the use of vericiguat in subjects with HFpEF, the results are still limited and more studies are needed to appropriately position the drug in this disease.

DiscussionDespite the improvements achieved in recent years with the current treatments, patients with HF and especially those who have had a recent episode of decompensation are still at high risk of hospitalization due to HF and death during follow-up.7–9 Although the patient may maintain a certain degree of clinical “stability” for some time, HFrEF continues progressing due to the continued stimulation of the deleterious pathways and suppression of protective pathways.15,16

In consequence, the treatment of some but not all of these pathways is partial, insufficient treatment which does not prevent disease progression. Therefore, the focus of HF treatment must be based on stimulating protective pathways as well as inhibiting deleterious pathways. In this regard, clinical practice guidelines agree on the need for early treatment with drugs that have demonstrated prognostic benefits.24–26

Vericiguat, as a GC agonist, is able to stimulate the nitric-oxide-cGMP protective pathway.39–44 The VICTORIA study focused on a different population than those analyzed in contemporary clinical trials on HF. It included subjects with greater baseline risk, such as patients with HF with a LVEF < 45% and a recent HF decompensation episode (hospitalization in the previous six months or intensification with IV diuretics in the previous three months).55 Therefore, this study is in line with current clinical practice guidelines, as it would provide a response for patients who remain symptomatic despite initial HF treatment.

In the VICTORIA study, nearly 90% of patients achieved the target dose of 10 mg of vericiguat, which indicates that it is a very well-tolerated drug. In this clinical trial, in which patients received the optimal medical treatment for HF recommended by clinical practice guidelines, treatment with vericiguat translated into a significant reduction of 10% in the composite primary outcome variables of death due to cardiovascular causes or a first HF hospitalization, with a NNT of 24.

In addition, there is a rapid divergence of the event curves at four months which continues until the end of follow-up; an increase in the benefits can even be observed.55 Consequently, it is a treatment whose benefits will increase if it is started early in patients with HFrEF and maintained over time. A recent meta-analysis on the efficacy of GC stimulators confirms this benefit on cardiovascular events and show a good safety profile.68

Likewise, the benefit of vericiguat is independent of concomitant HF treatment, including sacubitril/valsartan, as well as of the time since hospitalization or a HF decompensation episode.55 This implies that vericiguat can be used independently of the patient’s baseline treatment and can be prescribed in patients with a previous episode of hospitalization due to recent decompensation or need for treatment intensification as well as in an early follow-up appointment after hospital discharge.

Therefore, vericiguat allows for optimizing treatment as soon as possible in order to obtain the maximum benefit. In addition, it is a particularly favorable drug in patients with chronic kidney disease (the VICTORIA study included patients with a glomerular filtration rate ≥15 mL/min/1.73 m2) given that vericiguat does not cause changes in renal function or sodium electrolyte disorders. It should also be noted that the drug’s efficacy and safety are independent of renal function.36,55 However, given that the maximum benefit of vericiguat is obtained in patients with NT-proBNP levels ≤8000 pg/mL,55 it is possible that depletion treatment must be intensified before starting treatment with vericiguat in subjects with natriuretic peptide figures above these levels.

Vericiguat has an excellent safety profile and the fact that it is not necessary to determine renal function and plasma electrolytes make it a drug that is easy to use and titer in routine appointments, including in teleconsultations, which is very important in the management of patients with HF.69

Lastly, it has been estimated that the use of vericiguat in clinical practice would be cost-effective, given that vericiguat leads to a significant reduction in hospitalizations due to HF (first episode and recurrences),70 which are the main determinant in the increase in healthcare costs associated with HF.14

In conclusion, vericiguat has been shown to be an effective, safe treatment in a population that presents with a very high number of events in a short period of time, such as patients with HFrEF and a recent HF decompensation episode. In these patients, early, multidisciplinary, comprehensive treatment is necessary. Its ease of handling and titration facilitate its use in routine clinical practice.

In regard to patients with HFpEF, outcomes with vericiguat, like other GC stimulators, are modest. Therefore, it cannot be recommended in this disease at present.53,54,60,71,72

FundingThe authors received no funding for the creation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interestJ.R. González-Juanatey reports fees for conferences and is a member of the advisory board of Bayer.

M. Anguita-Sánchez has received funding for consulting services and conferences from Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Pfizer.

A. Bayes-Genís has received funding for consulting services and conferences from AstraZeneca, Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lilly, Novartis, Vifor, and Roche Diagnostics.

J. Comín-Colet reports fees for conferences and is a member of the advisory board of Bayer.

A. García-Quintana has received funding for consulting services and conferences from Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, Boerhinger Ingelheim, Novartis, and Rovi.

A. Recio-Mayoral has received funding for consulting services and conferences from Bayer, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, and Vifor.

J.L. Zamorano-Gómez reports fees for conferences from Bayer.

J.M. Cepeda has received fees for consulting services and/or conferences from Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, and BMS-Pfizer.

L. Manzano has received compensation for consulting services and conferences from Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, and BMS-Pfizer.

Content Ed Net (Madrid, Spain) provided writing and editing assistance with funding from Bayer Hispania.

Please cite this article as: González-Juanatey JR, Anguita-Sánchez M, Bayes-Genís A, Comín-Colet J, García-Quintana A, Recio-Mayoral A, et al. Verici- guat en insuficiencia cardíaca: de la evidencia científica a la práctica clínica. Rev Clín Esp. 2022;222:359–369.