To analyse changes in health care activity, time of referral and diagnosis intervals and the incidence of cancer during the first two years of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in a quick diagnosis unit.

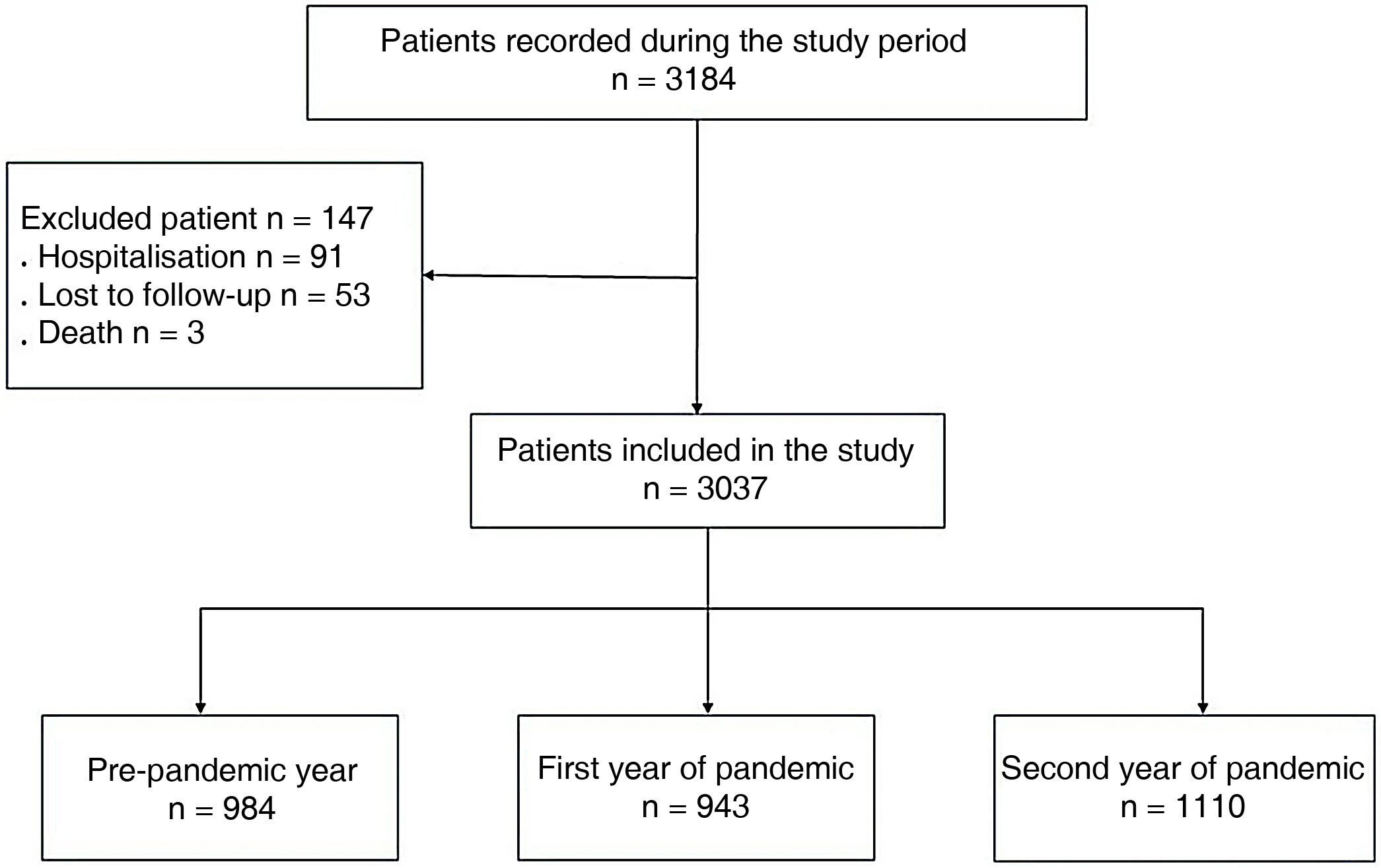

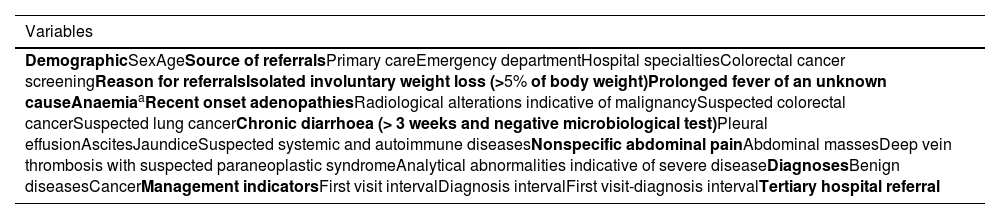

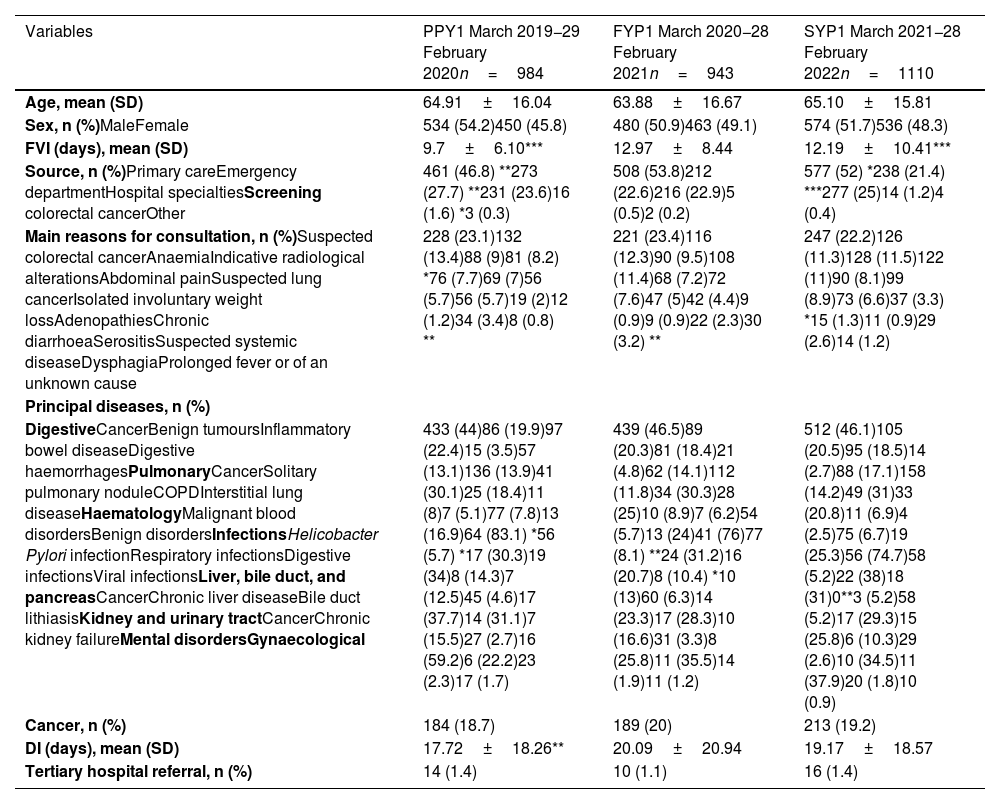

Materials and methodsA retrospective observational study was carried out during the prepandemic year (March 1, 2019, to February 29, 2020) and the first two years of the pandemic (March 1, 2020, to February 28, 2022). Demographic and clinical variables, the first visit interval, the diagnosis interval and the first visit-diagnosis interval were evaluated and compared.

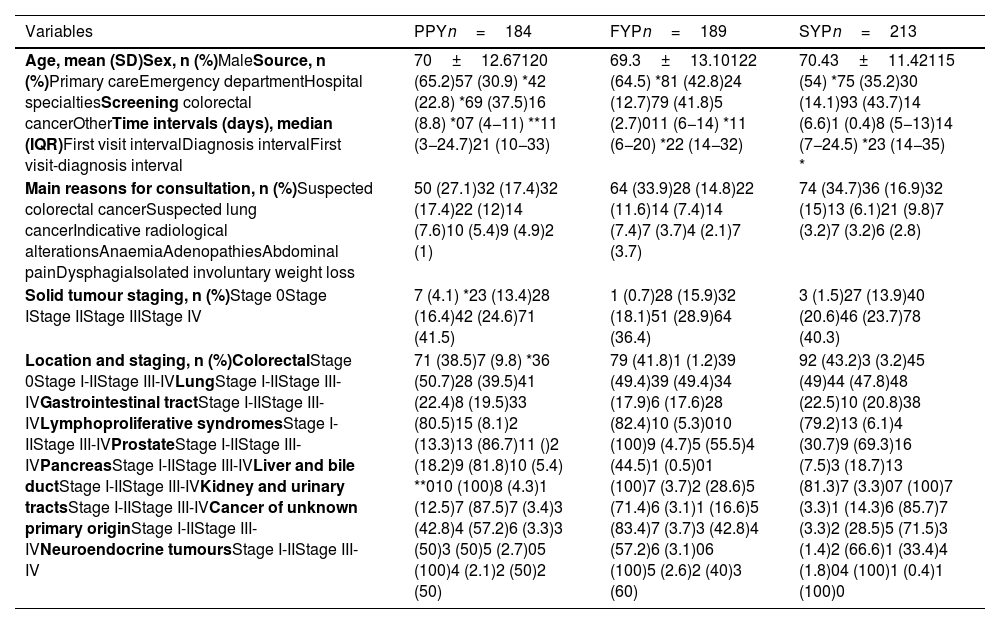

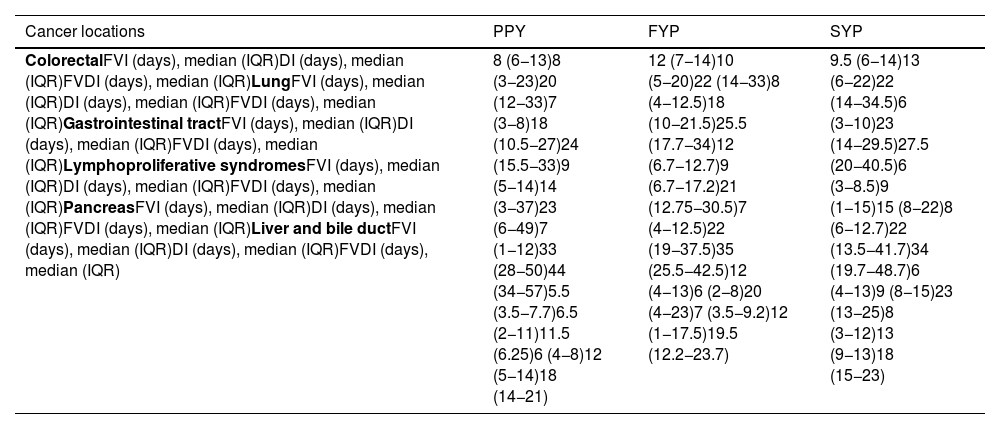

ResultsDuring the first pandemic wave, there was a reduction in referrals (−32.6%), which then increased 8.1% and 17.7% from the second wave until the end of the first pandemic year and the second pandemic year, respectively. An increase in referrals to primary care and a decrease in emergencies were identified. The increase in cancer diagnoses of 2.7% and 15.7% in the two years of the pandemic was proportional to the increase in referrals. No changes were observed in benign processes or in cancer locations and stages. The first visit interval was higher for benign diseases (p<0.0001). A prolongation of the diagnosis interval was observed in cancer patients, although during the three years of the study the median was <15 days.

ConclusionsThe impact of the pandemic affected the length of intervals and the origins of referrals. The quick diagnosis units constitutes and urgent complementary cancer diagnostic route with a high diagnosis yield.

Analizar el impacto en la actividad asistencial, tiempo de los intervalos de derivación y diagnósticos y la incidencia de cáncer durante los dos primeros años de pandemia por SARS-CoV-2 en una Unidad de Diagnóstico Rápido.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo observacional realizado durante el año prepandémico (1 marzo 2019-29 febrero 2020) y los dos primeros años de pandemia (1 marzo 2020-28 febrero 2022). Se evaluaron y compararon variables demográficas, clínicas, el intervalo de la primera visita, el intervalo diagnóstico y el intervalo primera visita-diagnóstico.

ResultadosDurante la primera ola pandémica hubo una reducción de derivaciones (-32,6%), registrándose desde la segunda ola hasta el final del primer año y segundo año de pandemia un incremento del 8,1% y del 17,7%, respectivamente. Se identificó un incremento de derivaciones de atención primaria y disminución de urgencias. El aumento de diagnósticos de cáncer del 2,7% y 15,7% en los dos años de pandemia fue proporcional al incremento de derivaciones. No se observaron cambios en procesos benignos ni en las localizaciones y estadiajes del cáncer. El intervalo de la primera vista fue superior en enfermedades benignas (p<0,0001). Se objetivó una prolongación del intervalo diagnóstico en pacientes con cáncer, aunque durante los tres años del estudio la mediana fue < 15 días.

ConclusionesEl impacto de la pandemia incidió en el tiempo de los intervalos y en las procedencias de las derivaciones. La unidad de diagnóstico rápido constituye una ruta diagnóstica de cáncer complementaria de carácter urgente con un alto rendimiento diagnóstico.

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<