This work aims to explore attitudes regarding the management of elderly or frail patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the routine clinical practice of a multidisciplinary group of physicians in Spain.

MethodsA mixed survey was used that included both Delphi and opinion, attitude, and behaviour (OAB) questions. Perceptions in primary care (n = 211) and hospital care (n = 80) were compared.

ResultsConsensus was obtained on all statements. Eighty-seven percent of participants considered that severe psychiatric disorders conditioned antidiabetic treatment and 72% that a psychocognitive assessment is as relevant as the assessment of other comorbidities. Hospital care physicians more frequently considered that comorbidity affects self-care (95.0% vs. 82.9%), that a lack of de-intensification is a form of therapeutic inertia (88.8% vs. 76.3%), that classifying older adults as frail is fundamental to choosing targets (96.3% vs. 87.7%), that de-intensification of antidiabetic treatment and control of cardiovascular risk factors should be considered in those over 80 years of age (90.0% vs. 78.7%), and that type 2 diabetes mellitus predisposes patients to sarcopenia (86.3% vs. 71.6%). The usefulness of clinical guidelines was more highly valued among primary care participants (79.1% vs. 72.5%).

ConclusionsThere is room for improvement on several aspects of managing elderly or frail patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, including inertia in treatment de-intensification, conducting a psychocognitive assessment, or the identification of frailty and sarcopenia.

Explorar actitudes en la práctica clínica habitual de un grupo multidisciplinar de médicos en España en el manejo de pacientes de edad avanzada o frágiles con diabetes mellitus tipo 2.

MétodosSe utilizó una encuesta mixta tipo Delphi y preguntas de opinión, actitud y comportamiento. Se compararon las percepciones en atención primaria (n = 211) y en atención hospitalaria (n = 80).

ResultadosSe obtuvo consenso en todos los enunciados. El 87% de participantes consideró que los trastornos psiquiátricos graves condicionan el tratamiento antidiabético y el 72%, que la evaluación psicocognitiva es tan relevante como la del resto de comorbilidades. Los médicos de atención hospitalaria consideraron con mayor frecuencia que la comorbilidad afecta al autocuidado (95,0% vs. 82,9%), que la ausencia de desintensificación es una forma de inercia terapéutica (88,8% vs. 76,3%), que clasificar al adulto mayor como frágil es fundamental para elegir objetivos (96,3% vs. 87,7%), que debe valorarse la desintensificación del tratamiento antidiabético y el control de factores de riesgo cardiovascular en mayores de 80 años (90,0% vs. 78,7%) y que la diabetes mellitus tipo 2 predispone a la sarcopenia (86.3% vs. 71,6%). La utilidad de las guías clínicas fue más valorada entre los participantes de atención primaria (79,1% vs. 72,5%).

ConclusionesExisten aspectos susceptibles de mejora en el manejo de pacientes de edad avanzada o frágiles con diabetes mellitus tipo 2: la inercia en la desintensificación del tratamiento, la evaluación psicocognitiva, o la identificación de fragilidad y sarcopenia.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) is a disease closely linked to aging; its prevalence increases with age1. In Spain, two-thirds of patients with DM (of which more than 90% have DM2) are older than 65 years of age2 and more than one-third of the population over 75 years of age meets the diagnostic criteria for DM3.

International clinical recommendations on the management of DM2 focus on the presence of established cardiovascular disease, though nearly 80% of patients have non-cardiovascular comorbidities1. In fact, DM increases the risk of not only cardiovascular disease, but also of kidney injury, nontraumatic amputations, blindness, and psychiatric symptoms4–10. In the specific case of elderly patients, it increases functional disability, sarcopenia, cognitive impairment, depression, urinary incontinence, falls, and chronic pain11.

Clinical practice guidelines have been published which offer specific recommendations for this population, given the complexity of DM2 management when there are determinants such as comorbidities and age1,11–13. Nevertheless, the manner in which guidelines are followed and complied with is not always optimal and can jeopardize clinical outcomes14–18.

This study aims to analyze the knowledge, barriers, and attitudes in the management of elderly patients with DM2 and/or comorbidities among primary care (PC) and hospital care (HC) specialists.

MethodsThis study is a national, multicenter project based on a mixed Delphi method/opinion, attitude, and behavior (OAB) survey. The OAB questions help expand upon the reasons underlying agreement or disagreement and go more in depth on the reasons why participants chose a specific option on the Delphi survey.

Data were collected in two phases (waves) by means of anonymous online questionnaires. The first wave of surveys was conducted in February and March 2020 and the second in May and June 2020.

The participants selected were PC and HC physicians whose routine practice included DM2 management. They were selected by means of non-probability sampling by clusters according to proportional geographical distribution and population criteria.

The mixed survey was designed by a scientific committee. It included a total of 25 Delphi-style statements and 13 OAB questions. Of these, the results of 12 statements and seven OAB questions focused on the determining role of comorbidities and old age in the management of patients with DM2 are presented.

The method used to predetermine the sample was a 95% confidence interval for a proportion of a finite population. The final sample size yielded a precision of ±5% for a 95% confidence interval. With a reference population of 46,934,628 inhabitants and 3055 PC centers, a representative sample of 300 physicians (PC and HC) from different regions of Spain was calculated.

The level of agreement on the Delphi statements was evaluated via a five-point Likert scale and was analyzed through two approaches: consensus measure (CNS) by means of the Tastle technique19 and the consolidation of five Likert scale categories into three (disagree, neutral, and agree). The threshold of consensus on the Delphi statements was a CNS ≥ 0.7. Statements which did not have a high degree of consensus (CNS ≥ 0.8) in the first wave were reevaluated in a second wave by the modification or inversion of the statement’s wording.

OAB questions were able to be answered either through single-choice, multiple-choice, or rating scale responses. For OAB questions which were single- or multiple-choice, the percentage each answer received was calculated and for questions with a rating scale, the median was calculated.

The Mann-Whitney U test and p value were used to evaluate differences between the responses from PC and HC specialists.

ResultsParticipantsA total of 296 physicians participated in the first wave and 293 participated in the second wave: 211 belonged to PC, 80 to HC, and 2 did not report their specialty. In terms of age, 21.6% of participants were younger than 46 years of age, 31% were between 46 and 55 years of age, and 47.7% were older than 55 years of age. In terms of sex, 65.5% were men. A total of 67.9% had been practicing medicine for 20 years or more. A total of 74.4% of participants stated that they followed clinical practice guidelines recommendations for the diagnosis of and follow-up on patients with DM2.

Results of the Delphi statementsAfter the second wave, consensus was achieved on the 12 statements presented and the CNS was 0.8 or greater on nine of them (Table 1). When the responses were consolidated into three categories, similar results were obtained in terms of percentage (Appendix A, Fig. 1).

Consensus measure (CNS) obtained on the Delphi statements.

| Statements | CNS (n = 291) | CNS PC (n = 211) | CNS HC (n = 80) | MW-p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management of patients with comorbidities and determinants | ||||

| 1. The evaluation of cognitive capacities and psychological symptoms in patients with DM2 (distress, depression, anxiety, eating disorders) is as important as the rest of comorbidities and determinants | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.396 |

| 2. Comorbidity affects a patient’s capacity for self-care | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.000 |

| 3. The coexistence of severe psychiatric disorders in patients with DM2 conditions antidiabetic treatment | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.168 |

| 4. Patients with DM2-COPD who receive medium- or high-dose glucocorticoids as treatment for flare-ups of their lung disease must be specifically screened for glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia (self-measurement of capillary blood glucose) and adjustments of hyperglycemia treatment must be evaluated | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.021 |

| Management of elderly patients | ||||

| 5. A lack of treatment deintensification in cases in which no benefits have been demonstrated is a form of therapeutic inertia that can have repercussions on the patient | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.035 |

| 6. In elderly patients with DM2, glycemic control targets must be individualized based on their biological, psychological, and social characteristics | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.024 |

| 7. The classification of elderly adults with DM2 as frail is fundamental in choosing glycemic control targets | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.001 |

| 8. The available clinical guidelines provide practical, useful recommendations for the specific evaluation of individuals with DM2 and frailty | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.025 |

| 9. In elderly patients, DM2 is a predisposing factor to the onset of sarcopenia | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.008 |

| 10. In elderly patients over 80 years of age with DM2, it is necessary to evaluate if deprescribing/deintensifying antidiabetic treatment and treatment for the control of CVRF is appropriate | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.017 |

| 11. Treating hypertension provides benefits even in patients with DM2 who are very elderly | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.116 |

| 12. The fact that a patient with DM2 has some type of cognitive impairment (from a mild cognitive disorder to dementia) conditions the choice of treatment strategy | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.258 |

CNS: consensus measure; DM2: type 2 diabetes mellitus; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVRF: cardiovascular risk factors; MW-p: p value of the Mann-Whitney U test.

A total of 86.3% of participants considered that comorbidities affect a patient’s capacity for self-care. A total of 86.9% agreed that severe psychiatric disorders condition antidiabetic treatment. A total of 72.2% considered the assessment of cognitive capabilities and psychological symptoms to be as important as the rest of comorbidities and determinants (Appendix A, Fig. 1a).

A total of 79.7% of participants agreed that a lack of treatment deintensification is a form of therapeutic inertia with possible repercussions for the patient. The level of agreement was 90.7% on the individualization of glycemic control targets based on biological, psychological, and social characteristics and 90% on classification according to frailty for choosing glycemic control targets in elderly patients.

A total of 75.6% agreed that DM2 is a predisposing factor for the onset of sarcopenia. A total of 81.8% of participants considered the deintensification of antidiabetic treatment and treatment for other cardiovascular risk factors necessary in patients over 80 years of age. A total of 88.3% affirmed that cognitive impairment conditioned the choice of treatment strategy (Appendix A, Fig. 1b).

Comparison of responses from primary care vs. hospital careThere was greater agreement among HC physicians that comorbidity affects patient’s capacity for self-care (95.0% vs. 82.9%) (Appendix A, Fig. 1a). HC physicians showed greater agreement on the notion that a lack of deintensification is a form of therapeutic inertia (88.8% vs. 76.3%); on classifying older adults as frail when choosing glycemic control targets (96.3% vs. 87.7%); on the notion that DM2 is a predisposing factor to sarcopenia (86.3% vs. 71.6%); and on evaluating whether the deintensification of antidiabetic treatment and treatment for the control of cardiovascular risk factors is appropriate in patients older than 80 years of age (90.0% vs. 78.7%).

The percentage of agreement on the consideration that the available clinical guidelines provide practical, useful recommendations for the specific evaluation of individuals with DM2 and frailty was significantly greater among participants from PC than those from HC (79.1% vs. 72.5%) (Appendix A, Fig. 1b).

Results of the opinion, attitude, and behavior surveyThe onset of intolerable side effects, the presence of frailty, and the high risk of having hypoglycemic episodes were considered reasons for deintensification by more than 80% of participants (Appendix A, Fig. 2).

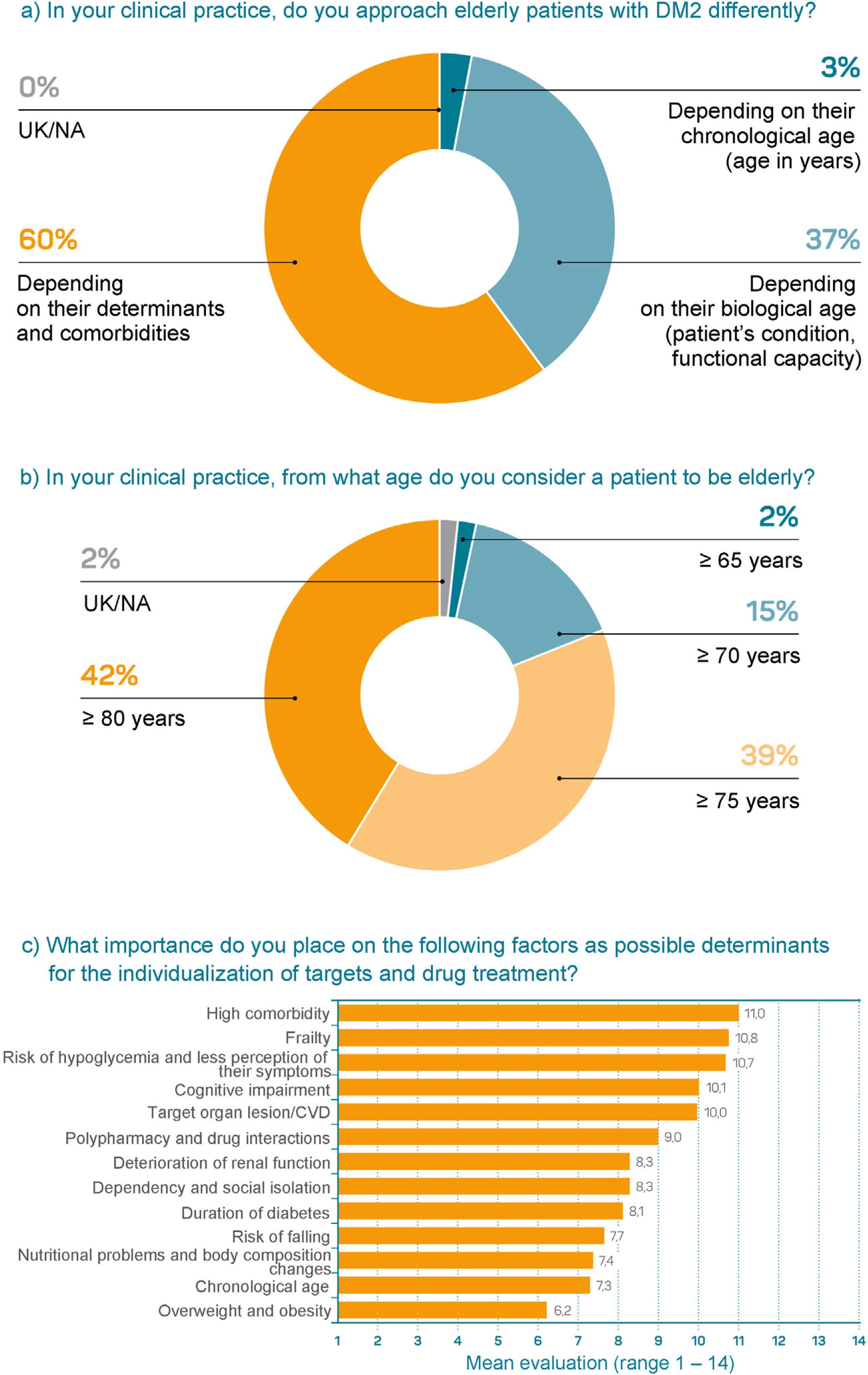

Sixty percent of participants considered a patient’s determinants and comorbidities to be determining factors when it comes to taking a different approach whereas 37% considered biological age to be more important; only 3% stated that they took chronological age into account (Fig. 1a). Forty-two percent of participants defined elderly patients as those over 80 years of age whereas 39% chose 75 years of age (Fig. 1b). The most important determinants for individualizing glycemic control targets and treatment were a high degree of comorbidity, frailty, risk of hypoglycemia, and cognitive impairment (Fig. 1c).

Questions about opinions, attitudes, and behaviors about determinants in the management of elderly patients (n = 296).

a) In your clinical practice, do you approach elderly patients with DM2 differently? b) In your clinical practice, from what age do you consider a patient to be elderly? c) What importance do you place on the following factors as possible determinants for the individualization of targets and drug treatment?

CVD: cardiovascular disease; DM2: diabetes mellitus type 2; UK/NA: unknown/not answered.

The most significant factors for defining frailty were functional decline, a high degree of comorbidity, cognitive impairment, and limited life expectancy (Appendix A, Fig. 3). None of the tools proposed for evaluating frailty had been used by more than 25% of participants. In fact, more than 50% of professionals stated they did not know of the FRAIL tool or the Fried criteria (Appendix A, Fig. 4a). The most used tools for evaluating sarcopenia were a subjective evaluation of muscle mass and strength and the determination of anthropometric measurements (Appendix A, Fig. 4b).

DiscussionThe data from our study show a high level of agreement among clinicians who attend to patients with DM2 regarding the importance of considering comorbidities in the management of DM2. In recent years, international clinical recommendations on DM2 management have mainly focused on the presence of established cardiovascular disease, which affects approximately 20% of the population with DM220. However, psychiatric problems are very prevalent in the population with DM28,9,21 and have been associated with a worse prognosis, treatment compliance22–24, quality of life25, and clinical outcomes24 and even with an increase in mortality26,27. Similar issues arise with cognitive impairment1,28. Despite this, 27.7% of participants did not believe that an assessment of a patient’s psychological or cognitive condition to be as important as the rest of comorbidities and determinants of DM2. Likewise, 13% did not believe that psychiatric disorders could condition antidiabetic treatment.

Elderly patients with DM2 are at greater risk of severe hypoglycemic episodes and associated hospitalization29,30. Given that among elderly patients, hypoglycemic episodes have been associated with a greater incidence of cognitive impairment, falls, fractures, stroke, and even greater mortality, clinical practice guidelines establish that avoiding hypoglycemic episodes must be priority therapeutic objective in these patients1,11,12. Setting more flexible glycemic control targets than in the general population is recommended1,31.

Despite these recommendations, only 38.9% and 28.7% of physicians establish these targets in patients considered elderly and frail, respectively32. In a recent Spanish study, 25.9% of patients were at severe risk of hypoglycemia and the majority received secretagogues or insulin33, despite the fact that treatment with antidiabetic agents with a low risk for hypoglycemia (metformin and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors) is recommended in elderly patients1.

A total of 79.7% of those surveyed in this study believed that not deintensifying treatment in patients in whom no benefits have been demonstrated is a form of treatment inertia with possible repercussions and that whether antidiabetic treatment deintensification is appropriate must be evaluated in patients older than 80 years of age. However, in our setting, overtreatment of DM2 has been described as common among elderly patients34. Studies in the United States of America confirm that the majority of elderly adults in average or poor health condition are subject to strict glycemic control and potentially overtreated35.

The definition of an elderly patient varies according to treatment guidelines for these patients: 75 years1, 70 years12, or even 65 years in guidelines from the USA11. This disparity is reflected among the study participants, though the most common response was 75–80 years of age. Even still, and as has been observed in other studies conducted in our setting32, chronological age was not considered to be a very important determinant in the approach to elderly patients.

In this study, the level of agreement on determining frailty for choosing glycemic control targets was especially high, especially among physicians who work in a hospital setting. Functional decline, a high degree of comorbidity, and cognitive impairment were the most valued factors in determining frailty. Despite the fact there are specific guidelines on the management of frail patients with DM13 or that it is included on guidelines on elderly patients1,12, 22.7% of participants declared they did not know about or did not agree with recommendations in this regard.

Sarcopenia can lead to lower uptake of glucose in the muscle, hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, and lastly, to the onset of DM13,36. Likewise, DM2 is also a predisposing factor for the onset of sarcopenia37. Sarcopenia has been associated with greater progression of age-related functional limitation and even with a reduction in life expectancy38. However, 24.4% of participants did not agree that DM2 was a predisposing factor for the onset of sarcopenia, especially those in PC.

Our study found a low level of use of tools for evaluating frailty (<25%) and a high degree of lack of awareness of tests such as the FRAIL tool or the Fried criteria (>50%). In regard to sarcopenia, this work has also observed a low level of use of these aforementioned tests.

The results obtained in this study coincide with the most current guidelines on the importance of designing a treatment plan and setting glycemic control targets based on the comorbidities, functional and cognitive capacity, mood disorders, and social support of elderly patients. In addition, room for improvement was noted regarding the integration of psychiatric symptoms and cognitive capacities into a comprehensive assessment of patients with DM2; the deintensification of antidiabetic treatment to meet more flexible targets set for elderly, frail patients; and the dissemination of specific guidelines on the management of these patients and the use of tools for evaluating frailty and sarcopenia.

This study has certain limitations. First, the sample of participants was selected, though this is a characteristic linked to Delphi studies, as they intend to include experts on the subject. Second, the use of closed responses to OAB questions may introduce bias for having left out other response options. However, those considered the most important or common according to the scientific committee's judgment were included. In addition, the decision to include more options or use an open-text field would have made the questionnaire too long and possibly lead to a wide range of responses. Lastly, it is possible that interpretation of the statements or response options may have varied according to each participant. In any case, the questionnaire was reviewed by experts who belong to both PC and HC.

ConclusionsThis study observed a high level of agreement on the evaluation and treatment of elderly patients with DM2 and/or comorbidities among participating specialists, with some differences between PC and HC physicians. It is important to conduct a comprehensive assessment of these patients in order to individualize treatment and reduce the risk of hypoglycemia.

Room for improvement was noted on aspects such as the evaluation of psychiatric symptoms and cognitive capacity, the deintensification of antidiabetic treatment and flexibility of glycemic control targets, the dissemination of specific guidelines, and the evaluation of frailty and sarcopenia in the management of elderly or frail patients.

Conflicts of interestFrancesc Xavier Cos has provided consulting services and served as a speaker for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi and has participated as an investigator on studies funded by AstraZeneca, Novartis, Sanofi, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Ricardo Gómez-Huelgas has provided consulting services, served as a speaker, and participated as an investigator in studies funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, MSD, Janssen, and Esteve.

Fernando Gómez-Peralta has provided consulting services for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Esteve, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi and participated as an investigator in studies funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. He has served as a speaker for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Esteve, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

FundingThis work was funded by ESTEVE Pharmaceuticals, S.A., Spain.

The authors would especially like to thank the panel of primary care and hospital care physicians for their participation, Esteve Pharmaceuticals, S.A. for the support provided in the conduct of this study, IDEMM-FARMA S.L. for technical and methodological support, Montse Fontboté and Jemina Moretó for their medical writing support, and Francisco López for conducting the statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Huelgas R, Gómez-Peralta F, Cos FX. Evaluación de conocimientos, barreras y actitudes en el manejo de la diabetes tipo 2 en pacientes de edad avanzada: estudio Delphi en atención primaria y hospitalaria. Rev Clin Esp. 2022;222:385–392.