In recent decades, progressive population aging in developed countries has led to a significant increase in the number of people with at least one chronic medical condition. As a result, acquiring knowledge about chronicity in medical school is key for physicians to be able to provide proper management for these patients. However, the presence of chronicity in educational curricula is scarce and highly variable.

On the one hand, this work consisted of a review of the educational programs of the main medical schools on each continent with the aim of identifying whether they included chronicity and, on the other, a literature review focused on identifying educational projects in the field of chronicity.

The presence of chronicity in most medical schools’ curricula is marginal and only a few universities include specific skills or competences linked to chronicity. In most cases, this topic appears as a global, cross-curricular competence that students are supposed to acquire over the course of their entire education. The literature review retrieved 21 articles on innovative teaching projects on chronicity. Direct contact with chronic patients, most times as “health mentors,” the role of the student as a teacher, and continuous evaluation and feedback from all participants are the main characteristics of the projects analyzed. Some previously published experiences support the usefulness of innovative methodologies for better approaching this capital field in current medical practice.

Despite the current situation in which chronic patients consume most healthcare resources, the presence of chronicity in medical schools is marginal. However, a literature review did identify some useful experiences for improving education on chronicity in medical schools. Medical schools should change their academic curricula and redirect them towards providing students all the necessary tools for improving their knowledge on chronicity.

En las últimas décadas, el progresivo envejecimiento de la población en los países desarrollados ha provocado un aumento significativo del número de personas con al menos una enfermedad crónica. Como consecuencia, es fundamental que la formación pregrado en Medicina aporte conocimientos sobre la cronicidad, de forma que los médicos puedan proporcionar un manejo adecuado a estos pacientes. A pesar de ello, la presencia de la cronicidad en los currículos formativos de las facultades de Medicina es escasa y muy variable.

Este trabajo consistió, por un lado, en una revisión de los programas formativos de las principales facultades de Medicina de cada continente, con el objetivo de identificar si incluían aspectos relacionados con la cronicidad y, por otro, en una revisión bibliográfica enfocada a identificar proyectos educativos en el campo de la cronicidad.

La presencia de la cronicidad en los planes de estudio de la mayoría de las facultades de Medicina es marginal y solo unas pocas universidades incluyen habilidades o competencias específicas vinculadas a este campo. En la mayoría de los casos en los que sí aparece, este tema se refleja como una competencia global y transversal que los estudiantes deben adquirir a lo largo de toda su formación. La revisión bibliográfica identificó 21 artículos sobre proyectos docentes innovadores sobre cronicidad. Las principales características de los proyectos analizados son: el contacto directo con pacientes crónicos, la mayoría de las veces como «mentores de salud», el papel del estudiante como profesor y la evaluación y retroalimentación continuas de todos los participantes. Algunas experiencias previamente publicadas avalan la utilidad de metodologías innovadoras para una mejora en el abordaje de este campo en la práctica médica diaria.

A pesar de la situación actual, en la que los pacientes crónicos consumen la mayor parte de los recursos sanitarios, la presencia de la cronicidad en las facultades de Medicina es marginal. Sin embargo, la revisión bibliográfica realizada ha permitido identificar algunas experiencias útiles para mejorar la formación sobre cronicidad en nuestras facultades. Las facultades de Medicina deberían modificar sus currículos académicos y reorientarlos para proporcionar a los estudiantes todas las herramientas necesarias para mejorar sus conocimientos sobre cronicidad.

The progressive aging of the global population and the inversion of the population pyramid in developed countries in recent decades, which has been linked to economic, healthcare, and social advances, has led to a situation in which previously fatal diseases, like ischemic heart disease, have turned into chronic conditions. As a result, the development of new complications and interactions between multiple chronic diseases in a single patient have increased the complexity of the management of many patients. In Spain, it is estimated that 34% of the population has at least one chronic health condition, a rate that increases to 78% among people 65 years of age or older.1

This new challenge affects not only daily clinical practice, but also medical schools and their way of teaching medicine. Indeed, Mateos-Nozal et al. analyzed the Spanish medical education system and identified a huge deficit in the field of geriatrics and chronicity.2 They proposed several solutions focused on innovations in teaching methods.3 In the United States of America, the American Medical Association’s Accelerating Change in Medical Education initiative started a working group in 2016 with the aim of improving undergraduate education on chronic diseases and chronicity; the group has proposed 11 core competences on this subject.4

Beyond geriatrics and in light of the increasing number of chronic patients of all ages, the current and future situation requires a profound rethinking of medical schools’ educational systems. This change should originate in the teaching professionals themselves and their perception of chronicity, which at present still seem to be quite negative.5 Most medical schools lack a specific program regarding chronicity and this area of knowledge is not an important part of either the curricular objectives or competences. Therefore, this work aims to assess the situation of undergraduate teaching on chronicity in medical schools worldwide, identify innovative projects in this area, and propose a possible improvement plan.

MethodsThis work was conducted in three different phases.

Review of the main medical schools’ academic curriculaFirst, a search was conducted to identify the main medical schools on each continent using the following indexes: Academic Ranking of World Universities,6 QS World University Rankings,7 and the Center for World University Rankings.8 Second, a representative sample from each continent was selected according to quality level, including at least the top five medical schools on each continent with the highest average combined scores on these three rankings. Considering the number of medical schools by country, we also selected at least the first five medical schools with the highest average scores from countries with a greater number of medical schools.

Once this process was complete, the information available on the medical schools’ websites was used to explore their academic curricula with the aim of identifying any references to chronicity, chronic diseases, or chronic patients. References related to geriatric medicine, comorbidity, or aging were also searched for. Schools in which there were no references to these terms in their curricula were considered to offer no instruction on chronicity. If any of the related key terms was identified, attempts were made to confirm the existence of a program or subject dedicated to education on chronicity by reviewing the subject’s syllabus or by contacting department heads or other professionals when this information was not sufficient for evaluating the presence of chronicity. For this step, the person in charge was emailed at their listed email address and he or she was directly asked if he or she considered that chronicity was fully and correctly addressed in the curriculum.

Programs were recorded as having a “Reference to chronicity” when the existence of specific teaching programs or subjects on chronicity was confirmed. Programs were recorded as having a “Potentially related subject” when some link to chronicity was found, but there was a lack of specific education on chronicity (Tables 1 and 2).

Overview of Spanish medical schools’ academic curricula and the presence of subjects related to chronicity.

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| University of Santiago de Compostela | No | Palliative Medicine and Geriatrics | 4th |

| University of Oviedo | No | No | – |

| Autonomous University of Madrid | No | Geriatrics | 5th |

| Complutense University of Madrid | No | No | – |

| University of Valencia | No | Physiology of Aging | Opt |

| University of Extremadura | No | Family Medicine and Geriatrics | 5th |

| Miguel Hernández University of Elche | No | No | – |

| University of Alcalá de Henares | No | No | – |

| University of Granada | No | No | – |

| University of Seville | No | Geriatrics and Palliative Care | 5th |

| University of Málaga | No | No | – |

| Jaume I University of Castellón | No | No | – |

| University of La Laguna | No | No | – |

| University of Córdoba | No | Clinical integration: the multiple comorbidity patient | 5th |

| University of Cádiz | No | No | – |

| University of Castilla la Mancha | No | No | – |

| University of Salamanca | No | Geriatrics and Family Medicine | 6th |

| University of Murcia | No | No | – |

| University of Barcelona | No | No | – |

| University of Zaragoza | No | Geriatrics, Infectious Diseases and Emergencies | Third |

| Public University of Navarre | No | Geriatrics and Palliative Care | 6th |

| University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | No | Geriatrics and Palliative Care | 5th |

| Pompeu Fabra University of Barcelona | No | No | – |

| University of the Basque Country | No | No | – |

| University of Cantabria | No | No | – |

| University of the Balearic Islands | No | Geriatrics | 5th |

| University of Girona | No | Fragility and dependence | Opt |

| Vital continuity, changes in the organism: aging | 6th | ||

| Rovira i Virgili University of Tarragona | No | Geriatrics | 4th |

| University of Lleida | No | No | – |

| Central University of Catalonia (Vic) | No | Vital continuity, changes in the organism: aging | 5th |

| Rey Juan Carlos University | No | No | – |

| Autonomous University of Barcelona | No | No | – |

| University of Navarra | No | No | – |

| European University of Madrid | No | No | – |

| Alfonso X el Sabio University | No | No | – |

| Catholic University of Valencia | No | No | – |

| San Pablo CEU University (Madrid) | No | Geriatrics and Palliative Care | 4th |

| Francisco de Vitoria University (Madrid) | No | Geriatrics | 4th |

| CEU Cardenal Herrera University (Valencia/Castellón) | No | No | – |

| Catholic University of Murcia | No | Geriatrics and Gerontology | 5th |

| International University of Catalonia (Barcelona) | Yes | Aging, Pluripathology and Chronicity | 5th |

Opt: optional course.

Review of the academic curricula of medical schools on different continents and the presence of subjects related to chronicity.

| Main European Medical Schools | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Course |

| University of the Algarve | No | No | – |

| University of Coimbra | No | No | – |

| University of Lisbon | No | Diseases of aging | Third |

| University of Porto | No | No | – |

| New University of Lisbon | No | No | – |

| France | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Course |

| Université Paris Sciences and Letters | No | No | – |

| Sorbonne University (Paris) | No | No | – |

| University of Paris | No | No | – |

| University of Grenoble-Alpes | No | No | – |

| University of Strasbourg | No | No | – |

| United Kingdom | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Course |

| Oxford University | No | Population Health 1: Medical Sociology | First |

| Cambridge University | No | No | – |

| Imperial College London | No | The aging patient | 5th |

| The University of Edinburgh | No | No | – |

| University of Manchester | No | No | – |

| Germany | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Course |

| Technical University of Munich | No | No | – |

| Ludwig Maximilian University (Munich) | No | No | – |

| Ruprecht-Karls University (Heidelberg) | No | No | – |

| Freie Universität (Berlin) | No | No | – |

| RWTH Aachen University | No | No | – |

| Italy | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Course |

| University of Bologna | No | No | – |

| Sapienza University of Rome | No | No | – |

| University of Padua | No | No | – |

| University of Milan | No | No | – |

| University of Pisa | No | No | . |

| Rest of Europe | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Course |

| University of Amsterdam (Netherlands) | No | Aging | First |

| Lomonosov Moscow State University (Russia) | No | No | – |

| Copenhagen University (Denmark) | No | No | – |

| KU Leuven (Belgium) | No | No | – |

| Lund University (Sweden) | No | No | – |

| Trinity College of Dublin (Ireland) | No | No | – |

| University of Helsinki (Finland) | No | No | – |

| University of Geneva (Switzerland) | No | No | – |

| University of Oslo (Norway) | No | No | – |

| University of Bern (Switzerland) | No | No | – |

| Utrecht University (Netherlands) | No | No | – |

| Uppsala University (Sweden) | No | No | – |

| Leiden University (Netherlands) | No | No | – |

| Groningen University (Netherlands) | No | No | – |

| Ghent University (Belgium) | No | No | – |

| Main US Medical Schools | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related competition | Course |

| Harvard University (Massachusetts) | Yes | Essentials of the profession | CC |

| Stanford University (California) | No | No | – |

| USC Caltech (Los Angeles) | No | No | – |

| University of Chicago | No | No | – |

| University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia) | No | No | – |

| Cornell University (Ithaca) | No | No | – |

| Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut) | No | No | – |

| Columbia University (New York) | No | No | – |

| University of Michigan (Ann Arbor) | No | No | – |

| Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore) | No | No | – |

| Northwestern University (Chicago) | No | Patient-Centered Medical Care | CC |

| University of California (San Francisco) | Yes | Longitudinal Clinical Experience | CC |

| New York University | No | No | – |

| Duke University (Durham) | No | No | – |

| Brown University (Providence) | No | No | – |

| CC: cross-curricular competence. | |||

| Main Canadian Medical Schools | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related competition | Course |

| University of Toronto | No | Patient-centered clinical assessment | CC |

| McGill University (Montreal) | No | No | – |

| University of British Columbia (Vancouver) | No | Learning in Community Medicine | CC |

| University of Montreal | No | No | – |

| University of Alberta | No | Integrated community care | CC |

| CC: cross-curricular competence. | |||

| Main Latin American Medical Schools | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Course |

| University of Buenos Aires (Argentina) | No | No | – |

| Autonomous University of Mexico | No | No | – |

| University of Sao Paulo (Brazil) | No | No | – |

| Pontifical Catholic University of Chile | No | No | – |

| Tecnológico de Monterrey (Mexico) | No | No | – |

| University of Chile | No | No | – |

| Universidad de los Andes (Colombia) | No | No | – |

| State University of Campinas (Brazil) | No | No | – |

| National University of Colombia | No | No | – |

| Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina | No | No | – |

| Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) | No | No | – |

| Federal University of Sao Paulo (Brazil) | No | No | – |

| Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Colombia) | No | No | – |

| Pontifical Catholic University of Peru | No | No | – |

| Austral University (Argentina) | No | No | – |

| University of Santiago de Chile | No | Geriatrics | 4th |

| University of Costa Rica | No | No | – |

| Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) | No | No | – |

| University of Concepción (Chile) | No | No | – |

| University of Antioquia (Colombia) | No | No | – |

| Universidad Panamericana (Mexico) | No | No | – |

| Federal University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) | No | No | – |

| National University of La Plata (Argentina) | No | No | – |

| Pontifical Bolivarian University (Colombia) | No | No | – |

| Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia | No | No | – |

| Main Asian Medical Schools | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Course |

| National University of Singapore | No | No | – |

| Nayang Technological University Singapore | No | Aging | 2nd |

| Tsinghua University of Beijing (China) | No | No | – |

| University of Hong Kong | No | No | – |

| Peking University of Beijing (China) | No | No | – |

| University of Tokyo (Japan) | Yes | Aging Science | Mand. |

| Fudan University of Shanghai (China) | No | No | – |

| Seoul National University (Korea) | Yes* | Environment and Chronic DiseasesEpidemiology of Chronic Diseases | * |

| Kyoto University (Japan) | No | No | – |

| The Chinese University of Hong Kong | No | No | – |

| Shanghai Jiao Tong University (China) | No | No | – |

| City University of Hong Kong | No | No | – |

| Zhejiang University (China) | No | No | – |

| University of Malaya (Malaysia) | No | No | – |

| National Taiwan University | No | No | – |

| Korea University | No | Disease in the elderlyGeriatricsGeriatric care in family medicine | Opt. |

| Osaka University (Japan) | No | No | – |

| Tohoku University (Japan) | No | No | – |

| Yonsei University (Korea) | No | No | – |

| Sungkyunkwan University (Korea) | No | No | – |

| Nagoya University (Japan) | No | No | – |

| Kyushu University (Japan) | No | No | – |

| Nanjing University (Japan) | No | No | – |

| University of Putra Malaysia | No | No | – |

| Hokkaido University (Japan) | No | No | – |

| *Offered as complementary postgraduate training (4-year degree). | |||

| Mand: mandatory subject, not linked to a specific course. Opt: optional subject. | |||

| Main Medical Schools in Oceania | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Course |

| The Australian National University | No | No | – |

| The University of Sydney (Australia) | No | No | – |

| The University of Melbourne (Australia) | No | No | – |

| The University of New South Wales (Australia) | No | No | – |

| The University of Queensland (Australia) | No | No | – |

| Main African Medical Schools | |||

| University | Reference to chronicity | Potentially related subject | Course |

| University of Cape Town (South Africa) | No | No | – |

| University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa) | No | No | – |

| Stellenbosch University (South Africa) | No | No | – |

| Cairo University (Egypt) | No | No | – |

| Alexandria University (Egypt) | No | No | – |

The review included the five main medical schools from United Kingdom, Germany, Portugal, France, and Italy and the 15 main medical schools from the remaining European countries. All Spanish medical schools were included in the review. Fifteen main medical schools from the United States of America, five from Canada, 25 from Latin America, 25 from Asia, five from Oceania, and five from Africa were also included. In the end, 120 medical schools were included in the review in addition to the 43 Spanish medical schools. The complete list of the medical schools included is available in Tables 1 and 2.

Review of scientific articlesA literature review was conducted on the PubMed, Scopus, SciELO, and Dialnet databases using keywords with the following searching strategy: (((chronicity[Title/Abstract]) OR (chronic disease[Title/Abstract])) AND ((teaching[Title/Abstract]) OR (medical education[Title/Abstract]) OR (medical school[Title/Abstract]) OR (undergraduate[Title/Abstract]))). The literature review was also expanded through related citations and by checking the reference section of the selected articles.

The main objective of this review was to identify publications on the teaching methods used in chronicity in medical studies. The inclusion criteria were articles with a description or evaluation of any teaching experience in the field of chronicity or articles with any proposals for new teaching methods in this field. Only articles which referred to undergraduate medical teaching were included; those which focused on postgraduate or specialized medical training were excluded. All duplicate articles or those referring to the same experience or project were excluded.

These criteria were applied through an initial reading of the title and abstract or through a deeper review of the article’s full content when necessary. The main key points extracted from the articles were: innovative proposal, use of technology, transmission of values and skills to students, existence of a completed project, and existence of a critical evaluation of results. The presence of these key points allowed for the articles to be considered high quality.

The information extracted from the selected articles was summarized as highlights regarding innovative aspects, specific target competences and skills, and type of self-assessment of outcomes.

Proposal for the implementation of innovative educational elements or programs on chronicityOnce all the available information was evaluated, a proposal was developed for innovative educational elements or programs related to chronicity that could be applied not only at our center (University of Santiago de Compostela Medical School), but also at any medical school interested in improving the teaching systems regarding chronicity.

ResultsReview of the main medical schools’ academic curriculaThe first notable difference regarding the various medical schools’ teaching programs is the educational curriculum itself, which may be organized in blocks of subjects, sets of competences, cross-curricular competences, or pre-defined itineraries with optional additional training.

A huge degree of variability can be observed not only when comparing schools in different countries, but also among medical schools in the same country, as shown in Tables 1 and 2. Nevertheless, one conclusion that can easily be drawn from a review of educational programs and curricula is that medical schools of greater importance and international recognition have changed the structure of their teaching into a competence-based curricula, with educational systems based on wide-ranging cross-curricular educational competences that are present throughout student’s entire medical education.9 Unfortunately, chronicity was not one of these cross-curricular competences in most cases and its presence in medical schools’ curricula is very unusual.

In the case of Spain, a subject that includes the concept of chronicity was only found in half of medical schools, with no mention made in the other half. No medical schools recognized chronicity as a cross-curricular competence. Our own institution, the University of Santiago de Compostela, is no exception: there is no mention of chronicity in the medical school educational program. Regarding the rest of Europe, as can be seen in Table 2, chronicity is not present as a global competence, though some medical schools in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany have recently made profound changes to their educational programs and have established competence-based programs.

In the United States of America, most medical schools had a competence-based educational program. Regarding chronicity, though its presence was not explicit, it was found in concepts related to quality of life, functional status, or the relationship between chronic diseases and social and work life. Some specific projects, like the Longitudinal Standardized Patient Case, have been implemented in some medical schools. This project focuses on the evaluation of chronic patients and the disease’s impact on daily life, in all cases with a high degree of satisfaction reported by the medical students.10–13 Other noteworthy strategies are those based on follow-up on the clinical progress of real chronic patients (Longitudinal Clinical Experience), rather than just simulated clinical cases. This strategy aims for students to become familiar with patients’ real lives and understand the disease’s impact on it.14

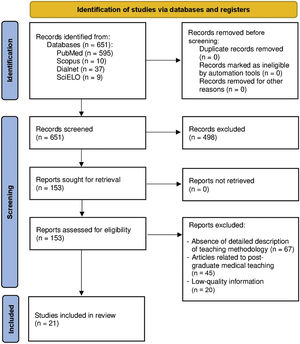

Review of scientific articlesThe search strategy retrieved 651 articles, of which 498 were excluded after reviewing the title and abstract because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. In a second round, another 112 articles were excluded due to absence of a detailed description of the teaching method or because they belonged to the field of postgraduate or specialized medical training. Of the remaining 41 articles, 21 were included in the review after reading and analyzing them in detail (Fig. 1).

Among the 21 articles analyzed, six which contained proposals for objectives or competences to be acquired through specific education on aspects related to chronicity are presented. The remaining 15 articles describe specific proposals for innovative teaching methods in the field of chronicity that have been carried out as pilot projects and, in most cases, have been subjected to a critical evaluation by students and/or teaching staff. The articles included in the review are detailed in Table 3.

Articles included in the literature review.

| Proposals on competencies and educational objectives | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | Country | Highlights |

| Thomas N. Lynn16 | 1964 | USA | - First proposal of specific educational curriculum on chronicity. |

| - Importance of preventive measures. | |||

| - Emphasis on functional impairment and dependence secondary to any chronic disease. | |||

| A. J. Cohen17 | 1998 | USA | - Relevance of psychosocial aspects. |

| - Emphasis on the acquisition of knowledge on measures to prevent complications. | |||

| - Learn to manage uncertainty. | |||

| - Training on proper resource management. | |||

| - Teamwork and multidisciplinary approach. | |||

| - Patient-centered approach to medicine. | |||

| Pham et al.18 | 2004 | USA | - Survey on educational needs on chronicity. |

| - Agreement on the need, but great variability on the priorities when making decisions. | |||

| Esselman et al.19 | 2009 | USA | - Importance of functional decline caused by chronic diseases. |

| - Need to know tools for functional evaluation. | |||

| - Role of rehabilitation in any chronically ill person. | |||

| Shi and Nambudiri20 | 2018 | USA | - Training on chronicity as a cross-curriculum competency. |

| - Need to involve all medical specialties in training in chronicity. | |||

| - Defense of the use of technology and telemedicine as facilitating tools. | |||

| Dekhtyar et al.5 | 2020 | USA | - Promotion of self-management of the disease. |

| - Learning based on evidence-based medicine. | |||

| - Correct use of information systems. | |||

| - Efficient use of community resources. | |||

| - Teamwork and communication. | |||

| - Promote healthcare of the highest quality and safety possible. | |||

| Experiences with innovative teaching methodology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | Country | Highlights |

| Stephenson et al.21 | 1996 | United Kingdom | - Pioneering experience based on workshops and seminars given by experts from different areas. |

| - Emphasizes the importance of learning about the disease from the patient's point of view. | |||

| Waddel and Davidson22 | 2000 | USA | - Direct learning from families involved in volunteer programs. |

| - The student goes into families’ homes to learn in situ. | |||

| - Introduces learning objectives such as prevention, service, and humanity. | |||

| Jerant et al.30 | 2005 | USA | -Role-playing workshops. |

| -Material to define attitudes and responses of major syndromes in chronic diseases. | |||

| -Group work and critical evaluation. | |||

| -Authors evaluate pre- and post-experience knowledge with the aim of significant improvement. | |||

| Diederiks et al.42 | 2006 | Netherlands | - Periodic interviews with chronic patients throughout a course. |

| - Modifies students’ perception of these patients. | |||

| - Big difference between what the students initially expected and the reality. | |||

| Yuen et al.23 | 2006 | USA | - At-home visits with chronic patients. |

| - Subsequent reflection task on these patients’ reality. | |||

| - Learning focused on the social-familial environment and possible interventions by the doctor to improve the patient’s daily life. | |||

| - Substantial change in the perception of care work for chronic patients after the experience. | |||

| McKinlay et al.26 | 2009 | New Zealand | - Three-phase system: direct patient learning, teacher-guided reflection, and presentation of results to the rest of students. |

| - Survey before and after the experience that shows an absolute change in the perception of chronicity by the students. | |||

| Shapiro et al.28 | 2009 | USA | - Filmed visits with patients with the aim of preparing an audiovisual record. |

| - Reflection on the patient’s daily life. | |||

| - Group presentation. | |||

| - Critical evaluation by the rest of the group. | |||

| LoFaso et al.29 | 2010 | USA | - Visits to patients and reflection on their life with chronic diseases. |

| - Creation of an artistic project of any kind to express the sensations and knowledge acquired. | |||

| - Group presentation and critical analysis. | |||

| Dent et al.43 | 2010 | USA | - 4-week rotation in a rural community. |

| - Training objectives of the rotation very focused on chronicity and the way of life of chronic patients. | |||

| - A change in students’ perception towards a much more positive opinion after the experience is observed. | |||

| Mullen et al.44 | 2010 | United Kingdom | - Interview with a chronic patient at home. |

| - Later second interview in another place with the main caregiver. | |||

| - Teaching objectives related to quality of life, disease progression, and impact on the daily lives of the patient and their caregivers. | |||

| Guenther et al.40 | 2014 | Australia | - Student self-directed education linked to rotations in primary care and focused on learning concepts related to chronicity. |

| - Excellent perception by students and good results in terms of knowledge acquisition. | |||

| Umland et al.25 | 2016 | USA | - Health mentor program in which the patient acts as a "teacher" for the students. |

| - Allows for follow-up on the patient for at least two years and evaluation of changes in the disease and impact on the patient’s life. | |||

| Remus et al.27 | 2016 | USA | - Combination of workshops, seminars, and patient visits. |

| - Training of the students themselves as those in charge of the teaching system. | |||

| - Analysis of results on knowledge acquired and opinions on the organizational system itself. | |||

| Liu et al.31 | 2016 | USA | - Direct involvement of students in the care of chronic patients. |

| - Regular meetings to monitor and evaluate decision-making. | |||

| - Critical evaluation by students and tutors. | |||

| Block et al.14 | 2018 | USA | - Longitudinal Standardized Patient Case Methodology. |

| - Students play the role of patients during several workshops separated in time. | |||

| - The management and execution of the project is carried out by the students themselves. | |||

In the first group of six articles, a paper from 1964 already discussed the challenge posed by chronic patients, the impact of disease on all areas of people’s lives, and the need to implement measures that go beyond mere medical treatment.15 In this sense, A. J. Cohen remarked in 1996 that existing educational deficits in this field led to an erroneous subsequent approach and poor resource management both when treating and preventing the development of chronic diseases.16

In 2004, Pham et al. published a survey of medical school department directors in the United States with the intention of proposing a common plan of action to improve medical training on chronicity. The results reflected a certain degree of agreement on the need for change, but enormous variability in the approach that each would propose.17

Other authors developed proposals based on students’ need to evaluate the functional repercussions of any chronic disease and the degree of disability it causes.18 Shi and Nambudiri advocated for extending medical training on chronicity to the entire educational period and all medical specialties, making chronicity one of the main cross-curricular competences in medicine.19

Recently, an expert panel comprising members from different universities in the United States of America have proposed six major objectives for improving medical teaching on chronicity that revolve around optimal data and resource management.4

The second group of 15 articles focused on proposals for specific educational projects on chronicity. One of the first works, published in 1996, was based on seminars and workshops and reported a high level of student satisfaction.20 Subsequently, other authors have made various proposals based on students learning directly by visiting patients’ family settings, such as the “Keeping Families Healthy” project,21 or a project which took place at Cornell University in which students conducted interviews with patients in their homes.22

The idea of bringing teaching on chronicity to the patient’s environment has been spreading in recent years through different projects based on the “Health Mentor” system, in which a student or group of students is assigned to a chronic patient and learn directly from his or her life experience with the disease.23,24

In general, the main structure of most projects could be summarized as follows:

- a)

The student or group of students is assigned to a patient who acts as a Health Mentor.

- b)

The student reflects throughout the experience by keeping a journal or completing questionnaires.

- c)

The student conveys his or her experiences and the knowledge acquired to other students.

The third point has been explored in different teaching projects on chronicity and in most, it is accompanied by completing surveys before and after the project which evaluate changes in students’ perceptions about chronicity.25 Some long-term experiences, like the teaching project developed at Harvard University, have shown great results by improving the teaching process every year through the students’ evaluation and self-management of the educational process.26

Other authors have published experiences in which students filmed interviews in order to create a documentary that they later presented in public27 or even translated their experiences with the patients into a work of artistic expression through painting, music, or other media.28 Some projects based on the Longitudinal Standardized Patient Case system have explored the use of roleplay dynamics and simulation systems for educational experiences on chronicity.13,29 Finally, the project conducted by Liu et al. at Yale University, in which students were involved not only in patient evaluations, but also in the decision-making process, merits mention.30

DiscussionThe first noteworthy finding of this review is the high degree of variability in medical education in general and in chronicity in particular in medical schools worldwide. In light of these differences, some authors have outlined different approaches for improving and standardizing educational programs at medical schools in different countries31–34 and minimum quality criteria have been also proposed.35 In this sense, the presence of concepts related to chronicity in most teaching programs is very scarce, despite the fact that some authors have suggested that chronicity should be a cross-curricular competence taught throughout medical school and covered in all medical specialties.19

This review found interesting proposals and projects linked to medical education in the field of chronicity that could be implemented in most universities worldwide to improve the knowledge and management of chronic patients. In many countries, like Spain, there are documents and projects regarding the approach to chronicity that highlight the importance of involving all healthcare professionals, but there are hardly any projects for reforming medical education, despite its capital importance.36,37 The first challenge universities face in this regard is to reflect the real situation of the population in most developed countries in medical school education and ensure the acquisition of enough competences and skills to properly care for chronic patients in an efficient, safe, and valuable way.

A key element for reforming medical education programs is the need to establish education on chronicity as a core competence implemented in a global, cross-curricular manner throughout the entire medical school education. This change should be preceded by a reorganization of the educational structure into a skills-and-competences-based program with universal minimum quality criteria.35,38

Other important concepts to be considered are professionalism, involvement, and cooperation during medical education. In this sense, in some of the projects analyzed, the students acted as educators and transmitters of information.13,26,39 In addition, continuous evaluation and feedback from students is another key for achieving excellence in medical education programs and should be applied to any project designed to improve medical education on chronicity.40 Indeed, it is remarkable that most innovative projects regarding medical education on chronicity include evaluation systems with the aim of improving the educational experience.26–30,41

It will also be necessary to update evaluation systems to focus on the skills and core competences for solving problems and making correct decisions in complex situations, such as those related to chronic patients. Teachers’ attitudes in this regard should focus on providing the student with adequate tools and resources to successfully handle these situations.40 Unfortunately, previous analyses have detected a great degree of variability in evaluation systems and poor adaptation to competence and skill evaluation, regardless of whether these exist and are described as teaching objectives in the program.42

Finally, it is also important to evaluate the potential financial costs when developing these projects. Most of the proposals analyzed entail practically no additional financial costs and the human or material resources required are minimal. Nevertheless, all medical schools interested in developing teaching projects on chronicity based on the acquisition of skills and competences will have to redirect resources and establish a network of teaching collaborators throughout all healthcare areas and levels.19 Everyday technological resources, like videoconference or social media applications, could be also used for simulations and virtual meetings.13,29

To date, there are no comparative analyses which have evaluated innovative training systems compared to traditional systems. Despite this, all local, specific evaluations described in different projects have showed a high degree student satisfaction and an improvement in their overall knowledge.

In light of these findings, a proposal for improving teaching on chronicity in the University of Santiago de Compostela Medical School, or indeed any other medical school, could be:

- -

The establishment of chronicity as a core cross-curricular competence whose consideration and influence should be reflected throughout the medical education period.

- -

The development of a Health Mentor Program, forming groups of students, patients, and tutors with follow-up throughout the medical education period.

- -

The creation of a network focused on chronicity that comprises teachers, physicians, patients, students, and other healthcare professionals for supervision and advising on education on chronicity.

Chronicity should be considered a major health problem and medical students’ education on concepts related to it must be a strategic objective of all medical schools. Despite this, this review showed that the presence of chronicity in most medical schools worldwide is marginal or nonexistent.

In light of previous experiences and recommendations, the educational approach to chronicity must understood as a cross-curricular competence that goes beyond a mere single subject, but rather be taught throughout a student’s education.

Strategies such as periodic workshops and seminars, regular visits to chronic patients in their environment for on-site learning, the development of programs based on simulations with technological support, and periodic group discussions are powerful tools with proven validity that should be included in any plan for improving education on chronicity.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestNone.