The Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (AEP) tool analyzes inappropriate hospital stays and admissions. This study aimed to adapt the AEP questionnaire in order to analyse the appropriateness of hospital admissions and stays in our healthcare reality.

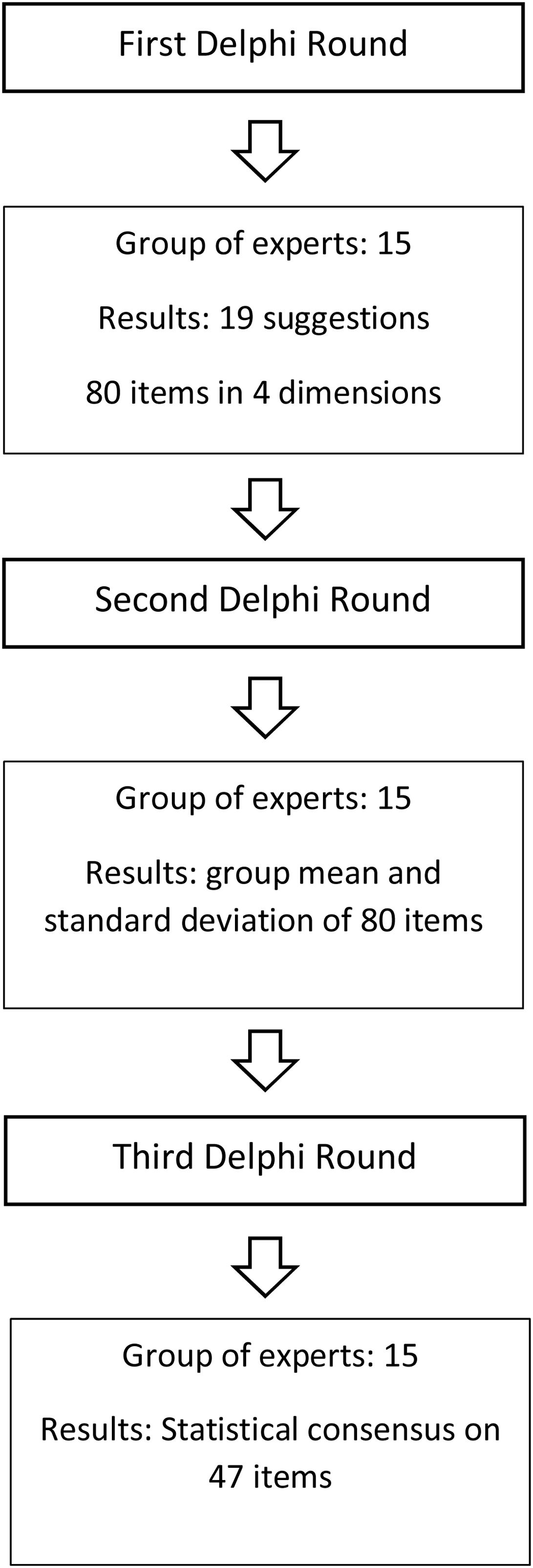

MethodsA study was conducted using the Delphi method in which 15 experts in clinical management and hospital care participated. The initial questionnaire items were taken from the first version of the AEP. In the first round, the participants contributed new items that they considered relevant in our current reality. In rounds 2 and 3, they evaluated 80 items according to their relevance using a Likert scale from 1 to 4 (maximum usefulness). Pursuant to the study’s design, AEP items were considered adequate if the mean score according to the experts’ evaluation was greater than or equal to 3.

ResultsThe participants defined a total of 19 new items. In the end, 47 items earned a mean score greater than or equal to 3. The resulting modified questionnaire include 17 items in “Reasons for Appropriate Admissions,” 5 in “Reasons for Inappropriate Admissions,” 15 in “Reasons for Appropriate Hospital Stays,” and 10 in “Reasons for Inappropriate Hospital Stays.”

ConclusionsThe identification according to expert opinion of priority items to determine the appropriateness of admissions and extended stays could be used in the future to help create an instrument to be used in our setting.

La herramienta Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (AEP) analiza las estancias e ingresos hospitalarios inadecuados. El objetivo de este estudio fue adaptar el cuestionario AEP para analizar la adecuación de los ingresos y las estancias hospitalarias en nuestra realidad asistencial.

MétodoSe desarrolló un estudio utilizando el método Delphi en el que participaron 15 expertos en gestión clínica y en asistencia hospitalaria. Los ítems del formulario inicial se conformaron a partir de la herramienta AEP tal y como fue definida en su primera versión. En la primera ronda los participantes aportaron nuevos ítems que consideraron relevantes en nuestra realidad actual. En las rondas 2 y 3 evaluaron 80 ítems según su relevancia mediante la utilización de una escala Likert del 1 al 4 (máxima utilidad). De acuerdo al diseño de nuestro estudio los ítems del AEP se consideraron adecuados si la media de la puntuación una vez evaluados por los expertos, era igual o superior a 3.

ResultadosLos participantes definieron un total de 19 nuevos ítems. Finalmente 47 ítems obtuvieron una puntuación media igual o superior a 3. El cuestionario resultante modificado consta de 17 ítems en “causas de admisiones adecuadas”, 5 en “causas de admisiones inadecuadas”, 15 en “causas de estancias adecuadas” y 10 en “causas de estancias inadecuadas”.

ConclusionesLa identificación de ítems prioritarios para determinar la adecuación de los ingresos y las estancias prolongadas en nuestro medio y según la opinión de los expertos, podría definir un futuro instrumento para su utilización en nuestro entorno.

In terms of clinical hospital management, handling hospital admissions and stays is a key aspect in the scheduling and daily activities of the centre. Over the last decade, increases in life expectancy and the number of chronic diseases has heightened health care demands, and with them, hospital care.1,2 This increase in medical and surgical complexity is reflected in the ever-increasing need for hospital admission/bed resources, as well the specific nature of the care given.3,4

In care quality programs, one of the primary objectives is to supervise how appropriately health care resources are being used and their optimisation to provide the services and care that is needed, particularly in critical situations (for example, when there is a lack of hospital beds, and many patients are waiting for emergency admission). Consequently, something that can help us with clinical management is to identify the rate of appropriate hospital admissions and stays, this being a goal that historically was carried out at the clinical judgement of reviewers, doctors, nurses, or trained external staff. This methodology offered low reliability, possible due to the subjective judgement of the reviewers, with this situation resulting in the development of protocolised tools with defined criteria and methodology.5

The published literature features multiple different experiences in which validated tools offer information about the appropriateness, or lack thereof, of hospital admissions and long hospital stays, including the AdeQhos® questionnaire and the Oxford Bed Study Instrument (OBSI), and other less-often used tools such as the Intensity Severity Discharge Criteria Set (ISD), the Delay Tool, the Managed Care Appropriateness Protocol (MCAP), the Standardized Medreview Instrument (SMI), and the Level of Care Criteria. While the organisation, number, and content of the criteria assessed differ with each tool, as does application to different population groups, they share a design based on variables that focus on patient’s clinical condition and the intensity of nursing care and required medical care.6–11

However, the most well-known and widely used tool is the Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol or AEP. It was described in 1981 by Gertman and Restuccia12 and involves a series of criteria or items used to evaluate the clinical condition of a patient and the intensity of the medical services and nursing care required. Many studies have determined the AEP is a valid and reliable tool.13,14 Ever since its creation, and due to its extensive use, subsequent versions have been developed: the Pediatric Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (PAEP) adaptation, the Surgical Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (SAEP) for surgical patients, the Community Hospital Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (CHAEP) for assessing intermediate care, the European version of the Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (EU-AEP),15 and the Spanish version of it.16 Nevertheless, its predictive capacity for short-term mortality is limited, with some people recommending against its use for evaluating the appropriateness of patient admission.17 On the other hand, changes in hospitalisation criteria due to the implementation of outpatient programs or innovative processes like home care services suggest that AEP must adapt to the new health care reality in our hospital environments.

This primary objective of this study was to adapt the AEP tool in order to analyse the appropriateness of hospital admissions and stays in our healthcare setting.

Material and methodsDesignTo adapt the questionnaire, a study was carried out by expert consensus using the Delphi Method.

The Delphi Method or technique is a systematic process of consulting, collecting, evaluating and tabulating the opinions of a panel of experts on a certain topic. For this process of analysis, the experts typically do not need to meet in-person. In general, the main advantage of this data collection method is the anonymity of the participants, the iteration, controlled feedback, and statistical response of the group which facilitates agreement on the final objectives.18

The term “quasi-anonymous” has been used to indicate that the survey respondents are known to the investigator and may known each other, but their opinions and judgements remain strictly anonymous.19 Anonymity among the participants is maintained via individual communication in the form of questionnaires. This enables the participants to freely state their suggestions without pressure from dominant experts.20

The iteration is achieved via a series of “rounds” of questionnaires which measure and score the study topics in a repetitive manner (typically 3 rounds). Between rounds, the group responses are analysed statistically to obtain the mean scores and standard deviations which are then communicated to the group to help reach a consensus.21 The three-round Delphi method used in this study was carried out during the months of February and August 2020 as described in Fig. 1.

ParticipantsThe sample of research group experts was comprised of professionals with at least 10 years of professional experience, of which at least 5 had to be dedicated to health care activities and 5 to clinical management. At least 2 years of history at the centre were required for participation. Our hospital is a high-technology university hospital with 600 hospital beds in an urban setting with a reference population of up to 1,500,000 residents for certain pathologies.

Data collectionFirst Delphi roundThe participants were contacted in February 2020 via a round of telephone calls and a subsequent formal invitation via email which explained the characteristics of the study and the schedule for the three evaluation rounds.

The form items from the first round were taken from the following versions of the AEP questionnaire: the American medical-surgical AEP, European AEP, and Spanish paediatric AEP.12,15,22 The questionnaire was structured according to the 4 dimensions of the AEP tool (Reasons for Appropriate Admissions, Reasons for Inappropriate Admissions, Reasons for Appropriate Stays, and Reasons for Inappropriate Stays).

The form, designed in Google Forms, was completed electronically. In this phase, the participants were asked to provide any additional items that they considered necessary. The form was reviewed by two members of the investigator’s team prior to being sent out.

Second Delphi roundAfter the first round, the means for each item were calculated and added to the questionnaire for the second round. The items suggested by the participants during the first round were also added to the form for evaluation. The participants were contacted again to complete the online questionnaire. They were asked to evaluate the items again according to their importance level on a Likert scale of 1–4, with the highest score given to items of the most importance.

Third delphi roundAfter the second round, the mean value for each item was calculated and added to the questionnaire for the third round. Once again, the participants were contacted by email to review and evaluate the items and asked to consider the mean values obtained in the second round. The evaluation score was identical to that used in the second round.

Statistical analysisThe participants’ sociodemographic variables were analysed using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and frequencies). The items from the evaluation rounds were analysed using the mean and standard deviation. Cohen's d mean difference was used to calculate the effect size using the mean values and standard deviations from rounds 2 and 3. The interpretation of the effect size is defined as small (0.2), medium (0.5) and large (>0.8).18 To compare the distribution of the variables between rounds 2 and 3 and provide a degree of agreement, the mean was used for each of the items. All the tests were conducted assuming a 95% confidence interval. The data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS v.25 software.

ResultsThe final sample for the panel of experts included 15 participants: 5 professionals dedicated to clinical management, 5 nurses, and 5 doctors from both medical and surgical specialties. A total of 5 women and 10 men participated. All had been linked to the centre for at least 15 years, of which at least 7 were in clinical practice.

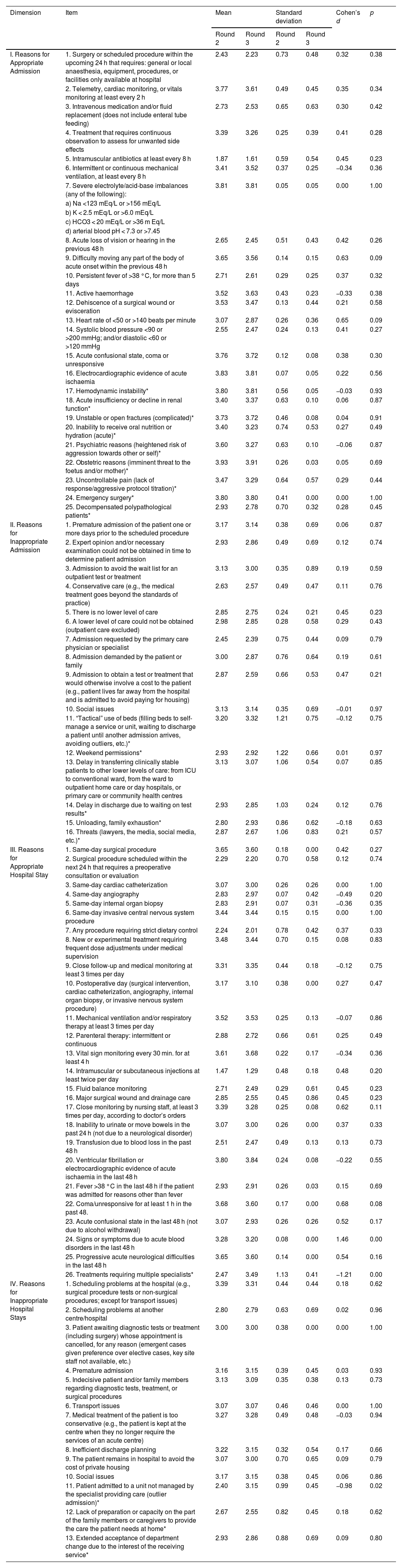

The experts provided 19 additional items to the initial 61-item form, resulting in an 80-item form at the end of the first round. The items were added within the four dimensions: 9 items for dimension I (Appropriate Admissions), 6 new items for dimension II (Reasons for Inappropriate Admissions), 1 new item for dimension III (Reasons for Appropriate Hospital Stays), and 3 items for dimension IV (Reasons for Inappropriate Hospital Stays). No relevant differences were observed between the means and the standard deviations between rounds 2 and 3. The standard mean values showed a small effect size in 60 items, medium in 17 items, and large in 3 items (Table 1).

Results of the Delphi evaluation rounds.

| Dimension | Item | Mean | Standard deviation | Cohen’s d | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 2 | Round 3 | Round 2 | Round 3 | ||||

| I. Reasons for Appropriate Admission | 1. Surgery or scheduled procedure within the upcoming 24 h that requires: general or local anaesthesia, equipment, procedures, or facilities only available at hospital | 2.43 | 2.23 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.38 |

| 2. Telemetry, cardiac monitoring, or vitals monitoring at least every 2 h | 3.77 | 3.61 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.34 | |

| 3. Intravenous medication and/or fluid replacement (does not include enteral tube feeding) | 2.73 | 2.53 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.30 | 0.42 | |

| 4. Treatment that requires continuous observation to assess for unwanted side effects | 3.39 | 3.26 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.28 | |

| 5. Intramuscular antibiotics at least every 8 h | 1.87 | 1.61 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.23 | |

| 6. Intermittent or continuous mechanical ventilation, at least every 8 h | 3.41 | 3.52 | 0.37 | 0.25 | −0.34 | 0.36 | |

| 7. Severe electrolyte/acid-base imbalances (any of the following): | 3.81 | 3.81 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| a) Na <123 mEq/L or >156 mEq/L | |||||||

| b) K < 2.5 mEq/L or >6.0 mEq/L | |||||||

| c) HCO3 < 20 mEq/L or >36 m Eq/L | |||||||

| d) arterial blood pH < 7.3 or >7.45 | |||||||

| 8. Acute loss of vision or hearing in the previous 48 h | 2.65 | 2.45 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.26 | |

| 9. Difficulty moving any part of the body of acute onset within the previous 48 h | 3.65 | 3.56 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.63 | 0.09 | |

| 10. Persistent fever of >38 °C, for more than 5 days | 2.71 | 2.61 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.32 | |

| 11. Active haemorrhage | 3.52 | 3.63 | 0.43 | 0.23 | −0.33 | 0.38 | |

| 12. Dehiscence of a surgical wound or evisceration | 3.53 | 3.47 | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.58 | |

| 13. Heart rate of <50 or >140 beats per minute | 3.07 | 2.87 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.65 | 0.09 | |

| 14. Systolic blood pressure <90 or >200 mmHg; and/or diastolic <60 or >120 mmHg | 2.55 | 2.47 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.27 | |

| 15. Acute confusional state, coma or unresponsive | 3.76 | 3.72 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 0.30 | |

| 16. Electrocardiographic evidence of acute ischaemia | 3.83 | 3.81 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.56 | |

| 17. Hemodynamic instability* | 3.80 | 3.81 | 0.56 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.93 | |

| 18. Acute insufficiency or decline in renal function* | 3.40 | 3.37 | 0.63 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.87 | |

| 19. Unstable or open fractures (complicated)* | 3.73 | 3.72 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.91 | |

| 20. Inability to receive oral nutrition or hydration (acute)* | 3.40 | 3.23 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 0.27 | 0.49 | |

| 21. Psychiatric reasons (heightened risk of aggression towards other or self)* | 3.60 | 3.27 | 0.63 | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.87 | |

| 22. Obstetric reasons (imminent threat to the foetus and/or mother)* | 3.93 | 3.91 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.69 | |

| 23. Uncontrollable pain (lack of response/aggressive protocol titration)* | 3.47 | 3.29 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.29 | 0.44 | |

| 24. Emergency surgery* | 3.80 | 3.80 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| 25. Decompensated polypathological patients* | 2.93 | 2.78 | 0.70 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.45 | |

| II. Reasons for Inappropriate Admission | 1. Premature admission of the patient one or more days prior to the scheduled procedure | 3.17 | 3.14 | 0.38 | 0.69 | 0.06 | 0.87 |

| 2. Expert opinion and/or necessary examination could not be obtained in time to determine patient admission | 2.93 | 2.86 | 0.49 | 0.69 | 0.12 | 0.74 | |

| 3. Admission to avoid the wait list for an outpatient test or treatment | 3.13 | 3.00 | 0.35 | 0.89 | 0.19 | 0.59 | |

| 4. Conservative care (e.g., the medical treatment goes beyond the standards of practice) | 2.63 | 2.57 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.76 | |

| 5. There is no lower level of care | 2.85 | 2.75 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.45 | 0.23 | |

| 6. A lower level of care could not be obtained (outpatient care excluded) | 2.98 | 2.85 | 0.28 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 0.43 | |

| 7. Admission requested by the primary care physician or specialist | 2.45 | 2.39 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.79 | |

| 8. Admission demanded by the patient or family | 3.00 | 2.87 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.19 | 0.61 | |

| 9. Admission to obtain a test or treatment that would otherwise involve a cost to the patient (e.g., patient lives far away from the hospital and is admitted to avoid paying for housing) | 2.87 | 2.59 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.21 | |

| 10. Social issues | 3.13 | 3.14 | 0.35 | 0.69 | −0.01 | 0.97 | |

| 11. “Tactical” use of beds (filling beds to self-manage a service or unit, waiting to discharge a patient until another admission arrives, avoiding outliers, etc.)* | 3.20 | 3.32 | 1.21 | 0.75 | −0.12 | 0.75 | |

| 12. Weekend permissions* | 2.93 | 2.92 | 1.22 | 0.66 | 0.01 | 0.97 | |

| 13. Delay in transferring clinically stable patients to other lower levels of care: from ICU to conventional ward, from the ward to outpatient home care or day hospitals, or primary care or community health centres | 3.13 | 3.07 | 1.06 | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.85 | |

| 14. Delay in discharge due to waiting on test results* | 2.93 | 2.85 | 1.03 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.76 | |

| 15. Unloading, family exhaustion* | 2.80 | 2.93 | 0.86 | 0.62 | −0.18 | 0.63 | |

| 16. Threats (lawyers, the media, social media, etc.)* | 2.87 | 2.67 | 1.06 | 0.83 | 0.21 | 0.57 | |

| III. Reasons for Appropriate Hospital Stay | 1. Same-day surgical procedure | 3.65 | 3.60 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.27 |

| 2. Surgical procedure scheduled within the next 24 h that requires a preoperative consultation or evaluation | 2.29 | 2.20 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.12 | 0.74 | |

| 3. Same-day cardiac catheterization | 3.07 | 3.00 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| 4. Same-day angiography | 2.83 | 2.97 | 0.07 | 0.42 | −0.49 | 0.20 | |

| 5. Same-day internal organ biopsy | 2.83 | 2.91 | 0.07 | 0.31 | −0.36 | 0.35 | |

| 6. Same-day invasive central nervous system procedure | 3.44 | 3.44 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| 7. Any procedure requiring strict dietary control | 2.24 | 2.01 | 0.78 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.33 | |

| 8. New or experimental treatment requiring frequent dose adjustments under medical supervision | 3.48 | 3.44 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.83 | |

| 9. Close follow-up and medical monitoring at least 3 times per day | 3.31 | 3.35 | 0.44 | 0.18 | −0.12 | 0.75 | |

| 10. Postoperative day (surgical intervention, cardiac catheterization, angiography, internal organ biopsy, or invasive nervous system procedure) | 3.17 | 3.10 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.47 | |

| 11. Mechanical ventilation and/or respiratory therapy at least 3 times per day | 3.52 | 3.53 | 0.25 | 0.13 | −0.07 | 0.86 | |

| 12. Parenteral therapy: intermittent or continuous | 2.88 | 2.72 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.49 | |

| 13. Vital sign monitoring every 30 min. for at least 4 h | 3.61 | 3.68 | 0.22 | 0.17 | −0.34 | 0.36 | |

| 14. Intramuscular or subcutaneous injections at least twice per day | 1.47 | 1.29 | 0.48 | 0.18 | 0.48 | 0.20 | |

| 15. Fluid balance monitoring | 2.71 | 2.49 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.23 | |

| 16. Major surgical wound and drainage care | 2.85 | 2.55 | 0.45 | 0.86 | 0.45 | 0.23 | |

| 17. Close monitoring by nursing staff, at least 3 times per day, according to doctor’s orders | 3.39 | 3.28 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.62 | 0.11 | |

| 18. Inability to urinate or move bowels in the past 24 h (not due to a neurological disorder) | 3.07 | 3.00 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.33 | |

| 19. Transfusion due to blood loss in the past 48 h | 2.51 | 2.47 | 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.73 | |

| 20. Ventricular fibrillation or electrocardiographic evidence of acute ischaemia in the last 48 h | 3.80 | 3.84 | 0.24 | 0.08 | −0.22 | 0.55 | |

| 21. Fever >38 °C in the last 48 h if the patient was admitted for reasons other than fever | 2.93 | 2.91 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.69 | |

| 22. Coma/unresponsive for at least 1 h in the past 48. | 3.68 | 3.60 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.68 | 0.08 | |

| 23. Acute confusional state in the last 48 h (not due to alcohol withdrawal) | 3.07 | 2.93 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.17 | |

| 24. Signs or symptoms due to acute blood disorders in the last 48 h | 3.28 | 3.20 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 1.46 | 0.00 | |

| 25. Progressive acute neurological difficulties in the last 48 h | 3.65 | 3.60 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.16 | |

| 26. Treatments requiring multiple specialists* | 2.47 | 3.49 | 1.13 | 0.41 | −1.21 | 0.00 | |

| IV. Reasons for Inappropriate Hospital Stays | 1. Scheduling problems at the hospital (e.g., surgical procedure tests or non-surgical procedures; except for transport issues) | 3.39 | 3.31 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.62 |

| 2. Scheduling problems at another centre/hospital | 2.80 | 2.79 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.96 | |

| 3. Patient awaiting diagnostic tests or treatment (including surgery) whose appointment is cancelled, for any reason (emergent cases given preference over elective cases, key site staff not available, etc.) | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| 4. Premature admission | 3.16 | 3.15 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.93 | |

| 5. Indecisive patient and/or family members regarding diagnostic tests, treatment, or surgical procedures | 3.13 | 3.09 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.73 | |

| 6. Transport issues | 3.07 | 3.07 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| 7. Medical treatment of the patient is too conservative (e.g., the patient is kept at the centre when they no longer require the services of an acute centre) | 3.27 | 3.28 | 0.49 | 0.48 | −0.03 | 0.94 | |

| 8. Inefficient discharge planning | 3.22 | 3.15 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 0.17 | 0.66 | |

| 9. The patient remains in hospital to avoid the cost of private housing | 3.07 | 3.00 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.09 | 0.79 | |

| 10. Social issues | 3.17 | 3.15 | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.06 | 0.86 | |

| 11. Patient admitted to a unit not managed by the specialist providing care (outlier admission)* | 2.40 | 3.15 | 0.99 | 0.45 | −0.98 | 0.02 | |

| 12. Lack of preparation or capacity on the part of the family members or caregivers to provide the care the patient needs at home* | 2.67 | 2.55 | 0.82 | 0.45 | 0.18 | 0.62 | |

| 13. Extended acceptance of department change due to the interest of the receiving service* | 2.93 | 2.86 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.09 | 0.80 | |

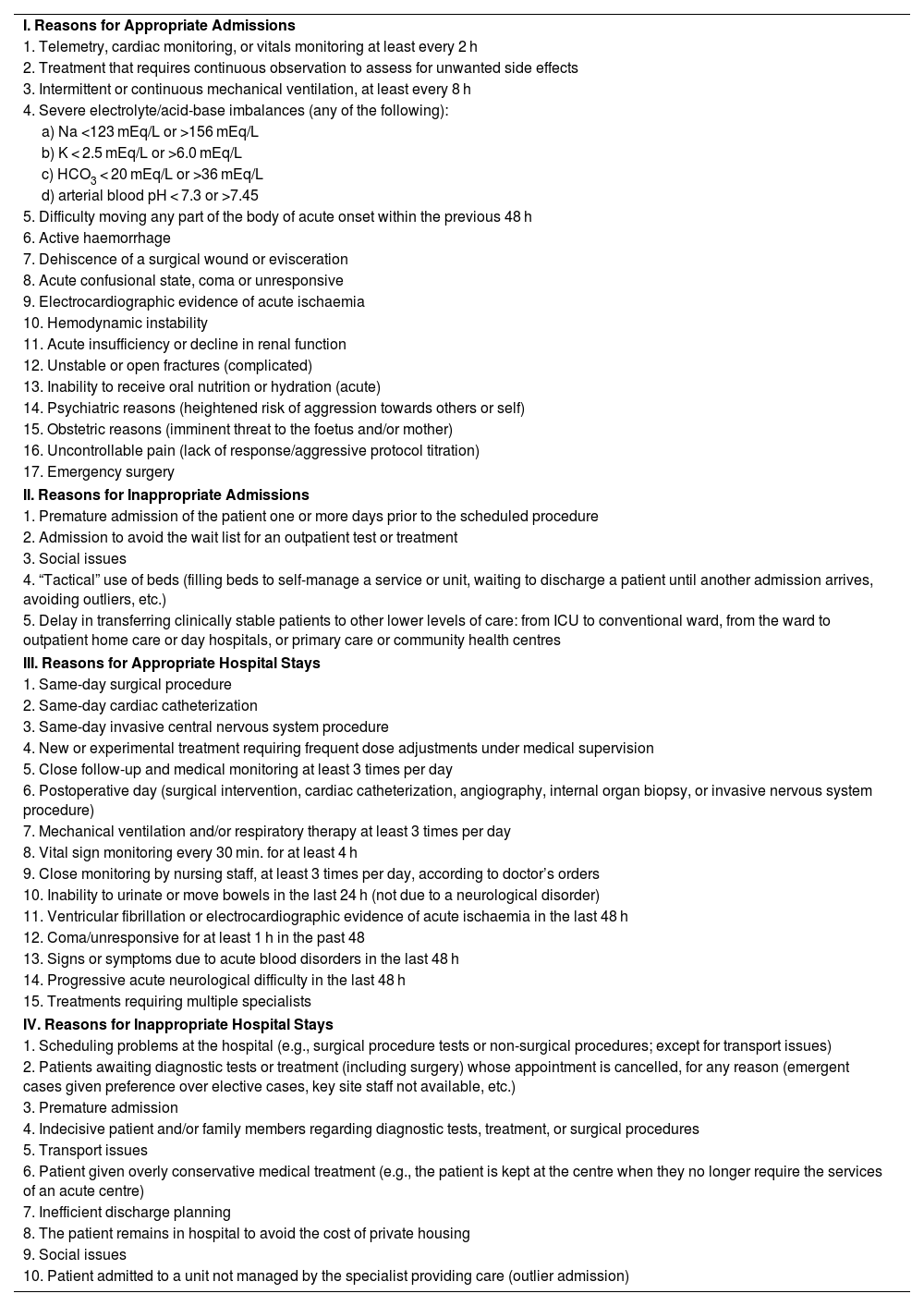

Lastly, the resulting questionnaire was made up of 47 items that consistently obtained a mean score equal to or greater than 3 by the end of the third round (Table 2).23 The number of items in all dimensions decreased between the initial form in round 1 and the final questionnaire proposal. The number of items in dimension I decreased from 25 to 17 items, in dimension II from 16 to 5 items, in dimension III from 26 to 15 items, and in dimension IV from 13 to 10 items.

List of items selected using the Delphi technique.

| I. Reasons for Appropriate Admissions |

| 1. Telemetry, cardiac monitoring, or vitals monitoring at least every 2 h |

| 2. Treatment that requires continuous observation to assess for unwanted side effects |

| 3. Intermittent or continuous mechanical ventilation, at least every 8 h |

| 4. Severe electrolyte/acid-base imbalances (any of the following): |

| a) Na <123 mEq/L or >156 mEq/L |

| b) K < 2.5 mEq/L or >6.0 mEq/L |

| c) HCO3 < 20 mEq/L or >36 mEq/L |

| d) arterial blood pH < 7.3 or >7.45 |

| 5. Difficulty moving any part of the body of acute onset within the previous 48 h |

| 6. Active haemorrhage |

| 7. Dehiscence of a surgical wound or evisceration |

| 8. Acute confusional state, coma or unresponsive |

| 9. Electrocardiographic evidence of acute ischaemia |

| 10. Hemodynamic instability |

| 11. Acute insufficiency or decline in renal function |

| 12. Unstable or open fractures (complicated) |

| 13. Inability to receive oral nutrition or hydration (acute) |

| 14. Psychiatric reasons (heightened risk of aggression towards others or self) |

| 15. Obstetric reasons (imminent threat to the foetus and/or mother) |

| 16. Uncontrollable pain (lack of response/aggressive protocol titration) |

| 17. Emergency surgery |

| II. Reasons for Inappropriate Admissions |

| 1. Premature admission of the patient one or more days prior to the scheduled procedure |

| 2. Admission to avoid the wait list for an outpatient test or treatment |

| 3. Social issues |

| 4. “Tactical” use of beds (filling beds to self-manage a service or unit, waiting to discharge a patient until another admission arrives, avoiding outliers, etc.) |

| 5. Delay in transferring clinically stable patients to other lower levels of care: from ICU to conventional ward, from the ward to outpatient home care or day hospitals, or primary care or community health centres |

| III. Reasons for Appropriate Hospital Stays |

| 1. Same-day surgical procedure |

| 2. Same-day cardiac catheterization |

| 3. Same-day invasive central nervous system procedure |

| 4. New or experimental treatment requiring frequent dose adjustments under medical supervision |

| 5. Close follow-up and medical monitoring at least 3 times per day |

| 6. Postoperative day (surgical intervention, cardiac catheterization, angiography, internal organ biopsy, or invasive nervous system procedure) |

| 7. Mechanical ventilation and/or respiratory therapy at least 3 times per day |

| 8. Vital sign monitoring every 30 min. for at least 4 h |

| 9. Close monitoring by nursing staff, at least 3 times per day, according to doctor’s orders |

| 10. Inability to urinate or move bowels in the last 24 h (not due to a neurological disorder) |

| 11. Ventricular fibrillation or electrocardiographic evidence of acute ischaemia in the last 48 h |

| 12. Coma/unresponsive for at least 1 h in the past 48 |

| 13. Signs or symptoms due to acute blood disorders in the last 48 h |

| 14. Progressive acute neurological difficulty in the last 48 h |

| 15. Treatments requiring multiple specialists |

| IV. Reasons for Inappropriate Hospital Stays |

| 1. Scheduling problems at the hospital (e.g., surgical procedure tests or non-surgical procedures; except for transport issues) |

| 2. Patients awaiting diagnostic tests or treatment (including surgery) whose appointment is cancelled, for any reason (emergent cases given preference over elective cases, key site staff not available, etc.) |

| 3. Premature admission |

| 4. Indecisive patient and/or family members regarding diagnostic tests, treatment, or surgical procedures |

| 5. Transport issues |

| 6. Patient given overly conservative medical treatment (e.g., the patient is kept at the centre when they no longer require the services of an acute centre) |

| 7. Inefficient discharge planning |

| 8. The patient remains in hospital to avoid the cost of private housing |

| 9. Social issues |

| 10. Patient admitted to a unit not managed by the specialist providing care (outlier admission) |

The study results show that, based on the initial items from the three AEP versions and the experts’ contributions, a consensus was reached for a 47-item tool that maintains the 4 dimensions from the original instrument.

The panel of experts evaluated the items based on the premise of evaluating the priority/importance of each criterion for determining the appropriateness of hospital admissions and stays with regard to the current reality of health care services provided to our population. The experts added 19 items to the initial proposal, suggesting that the AEP tool does not entirely reflect this reality.

Upon comparing the selected items with other instruments published in the literature, we observed that they feature criteria that are more specific to diagnosing the appropriateness of hospital admissions and stays. For example, the Oxford Bed Study Instrument (OBSI), developed in the 80 s and based on the AEP, evaluates 9 criteria that justify an appropriate hospital stay and presents 16 possible reasons for not discharging a patient. However, rather than being based on a review of medical histories, the methodology is developed using interviews with nurses and physicians caring for patients.24 Another example is the AdeQhos® questionnaire, developed in 2002 and based on the AEP and OBSI. It was designed to be administered by doctors during rounds. The average time required to complete it is 1 min and it evaluates 7 criteria that justify an appropriate hospital stay and 7 possible reasons for an inappropriate hospital stay. Therefore, AdeQhos® is a useful tool for quickly assessing the percent of inappropriate use of bed occupation in medical services, though not so much for identifying the reasons.25

One very positive aspect of using the AEP is that it features a long list of possible reasons for inappropriate hospital admission and/or stays, thus enabling interventions to be scheduled for more efficient management.

This study offers an update to a tool that can be very useful in our hospital setting, particularly during periods when hospitals experience significant strain to admit patients. The strength of this study is rooted in the use of the expert consensus (Delphi) method, which has been widely tested and is recognised as validated,18,26,27 and the use of an AEP-based form. Unlike other Delphi studies,28 in which participants are asked to suggest items in the first phase to create a questionnaire, we opted for a widely used and validated tool like the AEP. In addition, the selection of participants, which was adapted according to the inclusion criteria, with experience in hospital management and the medical and nursing fields, helped ensure a comprehensive and interdisciplinary view of the topic. This group of experts demonstrated excellent participation, with 100% across the three rounds of the questionnaire. However, our study also presents some limitations. Firstly, the first-round form was made up of three versions of the AEP, one of which was not available in Spanish, so the researchers had to provide a literal translation of it. On the other hand, use of the AEP by management individuals removed from the care setting could contribute to its inappropriate use.

Likewise, this study brings content validity to the tool and represents the first step towards validating a future questionnaire based on the characteristics of our centre. Using this adapted questionnaire, a systematic evaluation could be conducted to optimise the appropriateness of hospital admissions and stays that will result in a series of benefits. Firstly, improved quality of care via a decrease in inappropriate procedures, iatrogenic conditions, and nosocomial infections. Second, maintenance of the quality of hospital services with regard to indication, duration, frequency, and care level, as this reduction in care services would exclusively focus on unnecessary or inappropriate use or, in other words, on the aspect of care that does not actually benefit patients. This aspect would be particularly advantageous for avoiding “hospital-associated disability”, defined as sequelae that patients may experience with extended hospitalisation. This aspect particularly impacts the most fragile patients, who lose the ability to complete basic activities of daily living, with the main causes being a lack of sensory stimuli, bed rest, and malnutrition.29 Other benefits would include a decrease in costs due to a reduction in unnecessary hospitalisations, access to health care, the ability to reserve hospital care for those who need it, for whom it is indicated, and who benefit from it; and lastly, the opportunity to develop patient care standards and protocols that help guide medical decision-making.

Undoubtedly, the next study should evaluate the internal and external validity of the modified questionnaire via a consensus from experts on assessing the appropriateness of hospital admissions and stays with extensive clinical experience, and to observe how it behaves with a large cohort. Our group has already designed this analysis, which would be more valuable within the context of a multi-centre study.

Ethical considerationsThe study was assessed and approved by the reference Research Ethics Committee (REF: PI-19-228).

RecordRecord number in the reference Research Ethics Committee: PI-19-228.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific aid from public or private agencies nor from not-for-profit entities.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.