Post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is the most common complication following lumbar puncture. However, its incidence varies according to the series consulted. Different factors associated with its onset have been identified.

ObjectivesThe purpose of this study is to determine the incidence of PDPH and to identify predisposing factors for its appearance.

MethodProspective, descriptive study in 57 patients who underwent lumbar puncture procedures. To this end, variables associated with patient-related risk factors, clinical and procedural factors with the presence of PDPH were analysed. The incidence of PDPH was 38.6% and factors associated with onset included young age and previous history of headache.

ResultsThe incidence of PDPH was higher in women and presented greater intensity in this group, though studies with a larger sample size would need to be conducted.

ConclusionsWe must bear in mind the factors associated with the appearance of PDPH, which include: young age, history of headache, and the perception of procedural difficulty, to better inform patients and optimise the techniques used.

La cefalea pospunción dural (CPPD) es la complicación más frecuente tras la realización de una punción lumbar, sin embargo, su incidencia es muy variable según las series consultadas. Se han identificado distintos factores asociados a la aparición de esta.

ObjetivosEste estudio tiene como objetivo la determinación de la incidencia de CPPD y la identificación de factores predisponentes en su aparición.

MétodoSe lleva a cabo un estudio descriptivo, de carácter prospectivo en 57 pacientes a los que se les realiza una punción lumbar. Para ello, se han analizado variables relativas a factores de riesgo derivado del paciente, factores clínicos y del procedimiento con la presencia de CPPD. La incidencia de CPPD ha sido de 38,6% y entre los factores asociados a su aparición se ha identificado la edad joven y el antecedente de cefalea previa.

ResultadosLa incidencia de CPPD ha sido mayor en mujeres, siendo de mayor intensidad en este grupo, si bien es necesaria la realización de estudios con mayor tamaño muestra.

ConclusionesDebemos tener presente los factores asociados a la aparición de una CPPD como son: la edad joven, el antecedente de cefalea y la percepción de dificultad del proceso, para una mejor información a los pacientes y una optimización de la técnica empleada.

Lumbar puncture (LP) is a common procedure in medical practice and particularly in neurological conditions. Its fundamental purpose is diagnostic (analysis of cerebrospinal fluid [CSF], measurement of CSF opening pressure, isotope injection for cisternogram), though it is occasionally used therapeutically to relieve intracranial pressure or as an administration route in case of intrathecal treatment. Complications that present life-threatening risks to the patient rarely occur; however post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is the most common complication associated with this procedure. The frequency of onset varies, estimated to be 4–11%1 and up to 33–50% in patients from some series.2

The main proposed pathophysiological mechanism is CSF leak occurring at the site of the LP in the dura mater and has been observed via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in recent studies.3 These leaks cause intracranial hypotension with central compensatory vasodilation.4,5 On the other hand, they can cause the brain to sag within the skull due to a decrease in CSF volume, causing downward displacement of the brain structures that are most sensitive to intense pain (nerve endings and blood vessels) when assuming an upright position, resulting in the onset of orthostatic headache.1,6

According to the 2018 classification from the ‘International Headache Society’ (IHS),7 this is defined as a secondary headache attributable to a non-vascular cranial disorder that appears during the first five days following a LP and whose characteristics are similar to those of headaches caused by low CSF pressure, presenting as orthostatic headache and generally accompanied by neck pain, tinnitus, auditory impairment, photophobia, and/or nausea. This classification proposes the following as independent risk factors for the onset of PDPH: female sex, age between 31 and 50, prior history of PDPH, and needle bevel direction perpendicular to the long axis of the spine at the time of the LP.8

Other patient-related factors associated with PDPH onset include low body mass index (BMI) or high CSF opening pressure.9 Regarding procedure-related factors, those that stand out include not reinserting the stylet prior to removal of the LP needle10 and the use of classic needles (Quincke) versus atraumatic needles (Sprotte or Whitacre). The use of smaller diameter needles entails a lower incidence of PDPH.11,12 Oral hydration prior to the procedure has also been suggested as a protective factor.4

Various factors have not been shown to be directly involved in the onset of PDPH, including: rest (or lack thereof) following the procedure, volume of CSF extracted (expect for volumes >30 mL reported in some series with immediate onset of PDPH),1 CSF opening pressure, or CSF biochemical parameters analysed.9,13,14

However, there is little data on the involvement, or lack thereof, of other factors such as the experience of the professional performing the procedure, the technical difficulty of said procedure, patient position during the procedure, or the presence of other comorbidities in the patient’s history, particularly primary headaches,15 vascular diseases, or inflammatory diseases.2

The notable differences in PDPH incidence found in the published literature is what justifies our conducting this study. Likewise, despite being the most common complication following lumbar puncture, some predictive factors associated with the appearance of PDPH are still up for debate.

ObjectivesDetermine the incidence of PDPH in this series, as well as the associated risk factors, and to contribute to identifying patients at risk of developing PDPH in order to implement potential measures during or prior to the procedure to reduce PDPH frequency.

Material and methodsStudy designA longitudinal prospective observational study was performed in individuals who underwent LP for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes during an 8-month inclusion period. This study received approval from the Granada Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

Inclusion criteria: patients over the age of 18 referred for LP for diagnostic/therapeutic purposes according to clinical practice who signed the informed consent to be included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: under the age of 18. Cognitive impairment with GDS > 3 (moderate cognitive deterioration with loss of functional independence for activities of daily living).16

This study collected information regarding:

- 1)

Patient clinical and sociodemographic data. Age, sex, body mass index, personal history of previous lumbar puncture, headache, vascular risk factors (arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, hyperuricaemia, smoking, alcoholism), connective tissue diseases. The reason for lumbar puncture referral and caffeine intake prior to the procedure were recorded.

- 2)

Technical aspects from the procedure recorded by the professional who performed the lumbar puncture. This section also includes the procedure site (medical day hospital, hospital ward, or hospital emergency service), the professional who performed the lumbar puncture (area specialist or resident physician), patient position (lateral decubitus or seated), appropriate or inappropriate patient placement, difficulty palpating the intervertebral spaces (prior to puncture), administration or lack thereof of local anaesthesia, and size of the lumbar puncture needle (20 G or 22 G). Whether immediate access to the subarachnoid space was achieved or whether the lumbar puncture needle required repositioning, or if a second or third attempt was made, and the volume in mL of CSF extracted were all recorded as data. Capillary blood glucose was recorded prior to puncture as was the subjective perception of the professional performing the procedure of the overall difficulty. These data were collected following the lumbar puncture under regular clinical conditions and without modifying the procedure nor the information offered in regular clinical practice.

- 3)

Data regarding the onset of PDPH and CSF biochemical parameters. Patients were monitored for 7–14 days following the lumbar puncture via a telephone interview in which they were asked about the onset of orthostatic headache, day of onset after the lumbar puncture, VAS intensity,1–10 the presence of associated symptoms (nausea, vomiting, tinnitus, neck stiffness), treatment received, need to go to the emergency department or not, and headache duration (days). The cyto-biochemical and microbiological CSF results were reviewed on the lab test results platform.

The day of the LP, the patients were informed about the study and signed the informed consent form. All the participants filled out the regular informed consent for the lumbar puncture procedure as well as a second informed consent form for study participation. Participation was voluntary. The recorded data was coded in compliance with the Organic Law on the Protection of Personal Data (Law 15/1999).

Statistical analysisThe data collected from the aforementioned information sources was transferred to a spreadsheet (Excel) and analysed using IBM SPSS ® version 22.0 software. First, a univariate descriptive analysis of the sample was conducted, highlighting the main sociodemographic factors and those related to the intervention (lumbar puncture) and the outcome (PDPH) to characterise the study sample. Then, a bivariate analysis was performed using the principal statistical tests (chi-squared for associations between qualitative variables, Student’s t-test for comparison of means, the Pearson correlation for quantitative variables), after demonstrating normality and the conditions for application of each test.

If the conditions were not met, Fisher’s exact test was used to study the association between qualitative variables when a box was marked with an expected value of <5, which would prevent the interpretation of the chi-squared test from being correct.

ResultsA 57-patient sample was analysed, 24 (42.1%) males and 33 (57.9%) females with a mean age of 55 ± 16.2 years. Mean weight was 81.4 ± 23.7 kg, mean height 167.6 ± 7.2 cm, and average BMI 29.04 ± 8 kg/m2. Eight (14%) of the patients had undergone a lumbar puncture on a previous occasion.

A total of 24 patients had a history of headache (42.1%), of which 9 (37.5%) presented episodes compatible with tension headache, 2 (8.3%) migraine, 2 (8.3%) of them presented episodes of tension headaches and migraine episodes, and 5 (20.8%) mixed headache (tension headache with some characteristics of migraines during episodes such as: associated nausea, worsening during physical activity, or throbbing). Therefore, 9 patients (37.5) experienced headache with a migraine component. One patient (4.2%) presented orthostatic headache (suspected low CSF pressure), 3 patients (12.5%) headache compatible with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (normal imaging study), and in 2 patients (8.3%) the headache could not be classified due to non-specific characteristics, low frequency, and a case history that was difficult to classify the type of headache according to the IHS-II.

Regarding vascular risk factors, arterial hypertension and dyslipidaemia were the most common risk factors, present in 36.8% (21) and 29.8% of the patients, respectively. Eight patients (14%) had diabetes mellitus diagnoses and three (5.3%) hyperuricaemia. A total of 29.8% of the patients were active smokers at the time of the procedure, with mean intake of 10.4 ± 7.4 cigarettes per day. Four patients (3.5%) consumed alcohol on a daily basis. A history of cancer was confirmed in 4 patients (7.0%) (2 breast cancer, 1 lung cancer, and 1 follicular lymphoma). Three patients (5.3%) had histories of inflammatory/autoimmune diseases: psoriasis, ulcerative colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Three patients (5.3%) had fibromyalgia diagnoses and 4 (7%) of the patients had anxiety–depressive disorder.

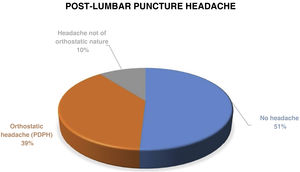

Post-lumbar puncture headache occurred in 28 patients (49.1%). In 22 of those (38.6), the headache was orthostatic in nature, compatible with post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) (Fig. 1).

Table 1 shows the data stratified by presence or absence of PDPH. It is worth noting that there was a larger proportion of females (48.5%) versus males (25%) in the PDPH group. The mean age of the patients who presented PDPH (49.4 years) was lower than that of the patients who did not present with headache (58.5 years). Of the 24 patients with a medical history of headache, 14 (58.3%) presented PDPH versus 8 (24.2%) of the patients without a history of headache (p = 0.013). No differences were observed between the types of prior headache and the appearance of PDPH. Nor was a relationship observed between the different vascular risk factors or the other medical history recorded and the onset of PDPH.

Sociodemographic variables and medical history.

| Variable | f (p)/x (s)* | PDPH | No PDPH | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 24 (42.1%) | 6 (25%) | 18 (75%) | 0.072** |

| Female | 33 (57.9%) | 16(48.5%) | 17 (51.5%) | |

| Age | 55 (16.2) | 49.4(17.0) | 58.5 (14.9) | 0.038*** |

| Weight (kg) | 81.4 (23.7) | 79.8 (32) | 82.5 (16.6) | 0.696 |

| Height (cm) | 167.6 (7.2) | 167.2 (6.7) | 167.8 (7.6) | 0.310 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.04 (8.0) | 28.7 (10.9) | 29.3 (5.6) | 0.80 |

| Variable | f (p)/x (s)* | PDPH | No PDPH | p value* |

| Prior LP | 0.466 | |||

| Yes | 8 (14.0%) | 2 (25%) | 6 (75%) | |

| No | 49 (86.0%) | 20 (40.8%) | 29 (59.2%) | |

| History of headache | 0.013*** | |||

| Yes | 24 (42.1%) | 14 (58.3%) | 10 (41.7%) | |

| No | 33 (57.9%) | 8 (24.2%) | 21 (63.3%) | |

| HTN | 0.272 | |||

| Yes | 21 (36.8%) | 6 (28.6%) | 15 (71.4%) | |

| No | 36 (63.2%) | 16 (44.4%) | 20 (55.6%) | |

| DL | 0.776 | |||

| Yes | 17 (29.8%) | 6 (35.3%) | 11 (64.7%) | |

| No | 40 (70.2%) | 16 (40%) | 24 (60%) | |

| DM | 0.697 | |||

| Yes | 8 (14.0%) | 4 (50%) | 4 (50%) | |

| No | 49 (86.0%) | 18 (36.7%) | 31 (63.3%) | |

| Hyperuricaemia | 0.553 | |||

| Yes | 3 (5.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | |

| No | 54 (94.7%) | 20 (37%) | 34 (63%) | |

| Tobacco use | 0.794 | |||

| Yes | 17 (29.8%) | 7 (41.2%) | 10 (58.8%) | |

| No | 40 (70.2%) | 15 (37.5%) | 25 (62.5%) | |

| Cigarettes/day | 10.4 (7.4) | 10.30 (8.7) | 10.67 (5.2) | 0.927 |

| Alcoholism | 0.518 | |||

| Yes | 2 (3.5%) | 0 | 2 (100%) | |

| No | 55 (96.5%) | 22 (40%) | 33 (60%) | |

| Anxiety depression | 0.635 | |||

| Yes | 4 (7%) | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | |

| No | 53 (93%) | 20 (37.7%) | 33 (62.3%) | |

| Cancer history | 0.288 | |||

| Yes | 4 (7.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 1 (25%) | |

| No | 53 (93.0%) | 19 (35.8%) | 34 (64.2%) | |

| Autoimmune history inflammatory | 0.530 | |||

| Yes | 3 (5.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | |

| No | 54 (94.7%) | 20 (37%) | 34 (63%) | |

| Fibromyalgia | 0.553 | |||

| Yes | 3 (5.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | |

| No | 54 (94.7%) | 20 (37%) | 34 (63%) | |

| Total | 57 (100%) | 22 (38.6%) | 35 (61.4%) | – |

The qualitative variables are presented as n(p), absolute frequency (percent or relative frequency), and the quantitative variables are presented as x(s), mean (standard deviation). The percentages are presented in rows in the PDPH and No PDPH columns. The p value corresponds to the statistical test comparing the PDPH and No PDPH groups. A comparison of means test (Student’s t-test) was used for the quantitative variables and the chi-squared test for the qualitative variables. Fisher’s exact test was used for qualitative variables with expected values of <5.

The indications for performing a lumbar puncture were: in 16 patients (24.6%) to perform CSF oligoclonal banding, in 27 (47.3%) to measure CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease (patients with suspected mild cognitive decline, GDS < 3), and 4 patients (7%) were undergoing neuromuscular pathology testing. In 4 of the patients (7%) the lumbar puncture was performed to measure intracranial pressure (ICP). The remaining 8 patients (14%) had other indications: suspicion of meningeal carcinomatosis, confusional syndrome, temporary vision loss, isotope cisternography, suspicion of meningitis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, determination of JC virus, and suspicion of autoimmune encephalitis. No differences were observed between the reason for performing lumbar puncture and the incidence of PDPH. At the time of the LP, 14 of the patients (24.6%) reported having ingested caffeinated beverages in the hours prior to the puncture. A total of 80.7% of the procedures were performed on an outpatient basis at the medical day hospital and 19.3% were performed in the neurology hospital ward. No statistically significant differences were observed regarding the incidence of PDPH and the location of the LP.

In 42 cases (73.7%) a neurology resident physician (MIR) performed the LP, in 6 (10.5%) a neurology specialist, and in 9 patients (15.8%) a resident physician from another medical speciality. The analysis showed no statistically significant differences regarding the incidence of PDPH between the LPs performed by professionals with different degrees of experience.

Regarding the technical aspects of the lumbar puncture: it was performed in a lateral decubitus position in 56 of the patients (98.2%). Patient positioning was considered ideal in 43 of them (75.4%); in 14 patients (24.6%), an adequate position could not be achieved due to physical limitations or poor collaboration. Once the patient was positioned, palpation of the spinous processes was performed immediately in 6 cases (10.4%) with the spinous processes visible. In 34 (57.4) of the patients, palpation of the spinous processes was easily done after taking anatomical references. In 9 patients (15.8%), some difficulty was had to select the anatomical space due to the depth of the spinous processes and/or irregularities in the backbone. Eight patients (14%) presented anatomical features that made it almost impossible to perform adequate palpation.

In 56 of the 57 (98.2%) procedures performed, local anaesthetic was administered first, and the lumbar puncture was performed using a 20 G spinal needle (a 22 G spinal needle used for the remaining procedures).

Immediate access to the subarachnoid space was achieved in 15 cases (26.3%), with reinsertion of the LP needle being necessary at least once in the remaining 42 patients (73.7%). A second attempt was required in 6 patients (22.8%), a third attempt in 4 patients (7%), and four attempts were needed for one patient. During the procedure, a total of 40.4% experienced self-limiting pain irradiating to the lower limbs (LL). There were no statistically significant differences between any of the variables related to the technical aspects of the LP and the appearance of PDPH.

The volume of extracted CSF was measured with an average volume of 4.75 ± 1.46 mL (95 ± 29.3 drops). The macroscopic appearance of the CSF was transparent in 34 cases (59.6%), slightly haematic in 18 (31.6%), and clearly haematic in 5 patients (8.8%). The mean number of red blood cells in CSF extracted was 1097.9 ± 5087.8 red blood cells; the average cell count was 3.6 ± 12.4 cells; mean protein count 52.4 ± 42.6 mg/dl. Mean glucose in CSF was 70.4 ± 16.9 mg/dL while the CSF/serum glucose ratio was 0.67 ± 0.18. Mean pre-puncture capillary blood glucose was 111 ± 33.6 mg/dL. There was no relationship between the macroscopic appearance of the CSF and the appearance of PDPH. Nor were the characteristics of the CSF related in a statistically significant manner to the appearance of PDPH.

Regarding the overall difficulty of the procedure according to the professional performing the LP, this was considered low in 27 cases (47.4%), medium difficulty in 21 procedures (36.8%), and high in 9 procedures (15.8%). Upon dichotomizing the “procedure difficulty” variable into “low difficulty” and “medium-high difficulty”, 14 of the patients (51.9%) from the low difficulty group developed PDPH versus 8 patients (26.7%) from the medium-high difficulty group (p = 0.051) (Table 2).

CSF extraction and overall procedure difficulty.

| Variable | f (p)/x (s)* | PDPH | No PDPH | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mL extracted in the LP | 4.75 (1.5) | 4.6 (1.6) | 4.8 (1.4) | 0.544 |

| Macroscopic appearance | 0.601 | |||

| Transparent | 34 (59.6%) | 15 (44.1%) | 19 (55.9%) | |

| Slightly haematic | 18 (31.6%) | 6 (33.3%) | 12 (66.7%) | |

| Haematic | 5 (8.8%) | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | |

| Pain irradiating to LL during the LP | 0.183 | |||

| Yes | 23 (40.4%) | 11 (47.8%) | 12 (52.2%) | |

| No | 33 (57.9%) | 10 (30.3%) | 23 (69.7%) | |

| Capillary blood glucose pre-procedure | 111.0 (33.6) | 105.2 (20.7) | 114.5 (39.3) | 0.341 |

| Overall difficulty of LP perceived by the physician | 0.159 | |||

| Low | 27 (47.4%) | 14 (51.9%) | 13 (48.1%) | |

| Mean | 21 (36.8%) | 6 (28.6%) | 15 (71.4%) | |

| High | 9 (15.8%) | 2 (22.2%) | 7 (77.8%) | |

| Dichotomous difficulty of LP as perceived by the physician | 0.051** | |||

| Low | 27 (47.4%) | 14 (51.9%) | 13 (48.1%) | |

| Medium-high | 30 (52.6%) | 8 (26.7%) | 22 (73.3%) | |

| Total | 57 (100%) | 22 (38.6%) | 35 (61.4%) | – |

The qualitative variables are presented as n(p), absolute frequency (percent or relative frequency), and the quantitative variables are presented as x(s), mean (standard deviation). The percentages are presented in rows in the PDPH and No PDPH columns. The p value corresponds to the statistical test comparing the PDPH and No PDPH groups. A comparison of means test (Student’s t-test) was used for the quantitative variables and the chi-squared test for the qualitative variables. Fisher’s exact test was used for qualitative variables with expected values of <5.

During the telephone interview held between 7- and 14-days post-LP, 28 patients reported experiencing a headache in the days following the procedure. For 22 of them, the headache was of an orthostatic nature due to low CSF pressure according to the PDPH definition. In the other 6 cases the headache presented non-specific characteristics or the typical headache characteristics normally experienced by the patient. The mean intensity of PDPH pain according to the visual analogue scale was 7.55 ± 1.82 on a scale of 0–10 in which 0 is no headache and 10 maximum intensity headache. For the PDPH intensity analysis, the following two groups were defined: low-moderate intensity headache (score of 6 or lower out of 10) and high intensity headache (score of 7 or higher out of 10). Eight patients presented low-moderate intensity PDPH (36.4%) while the remaining 14 patients presented high intensity PDPH (63.7%). Twelve of the women who presented PDPH (66.7%) experienced a high intensity headache versus 3 men (33.3%), p = 0.137. The 7 patients with medical histories of migraine headaches presented with PDPH (100%) and were classified into the high intensity group versus 4 (50%) of the patients without a history of migraine headache (p = 0.070).

The mean age of the patients with high intensity PDPH was 44.5 ± 16.5 years and 58.3 ± 15 in the PDPH group with an intensity score of 6 or below (p = 0.064). No differences nearing statistical significance were observed in the analysis of the remaining variables regarding the intensity of PDPH.

In 14 of the patients with PDPH (63.6%), the headache was associated with accompanying symptoms: 6 patients experienced dizziness, 6 nausea, 1 patient presented with photophobia, 4 patients reported neck pain or stiffness, 1 patient hearing alteration, and 1 patient reported self-limiting visual alterations. In 9 of the patients with PDPH (40.9%), headache onset began hours after the procedure was performed (within 24 h of the LP). In another 9 patients (40.9%), onset occurred on the second day post LP, and in 4 cases (18.2%) the headache started on day 3 following the lumbar puncture. The mean number of days until headache onset was 1.74 ± 0.73 days. The mean duration of the PDPH was 4.86 ± 2.53 days, with a minimum duration of 1 day and a maximum of 10 days. Four of the patients who presented PDPH (18.2%) required medical care for it, 1 of whom went to the emergency department and the remaining three consulted their primary care doctor.

Of the 22 patients who presented PDPH, 20 (90.1%) required oral analgesics, though none required parenteral treatment. Regarding the number of drugs, 16 (80%) of the patients who used some type of treatment were able to control their pain with one drug. The most commonly used drugs were paracetamol (12 patients) and NSAIDs (9 patients). Other drugs used included metamizole (4 patients), caffeine and codeine (1 patient each). No factors associated with a longer PDPH duration were identified in our patient cohort.

DiscussionThe incidence of PDPH in our patient cohort was 38.6%, just slightly below that found in another recent series, 52.8%,2 with a similar design.

Worthy of note is the variability in the incidence of PDPH in the various series reviewed, which we consider to be related to underdiagnosis given that it often presents with mild symptoms of varying duration. In our series, we found that up to 36.7% of patients developed mild-moderate PDPH (visual analogue scale score of 6 or below), and in none of the cases (even in case of high intensity headache) did patients require parenteral analgesic treatment. In the above-mentioned series,2 female sex and older age were identified as risk factors for PDPH. The results from our patient cohort are in line with that described above, with a higher incidence of PDPH in women, with the results of the analysis showing a trend towards statistical significance.

We found a tendency towards higher incidence of high intensity PDPH in women compared to men, though the results were not statistically significant. We found a similar tendency in younger patients and patients with a clinical history of headache.

A history of migraine-type headaches has been classically identified as a risk factor for the incidence of PDPH17; however, in recent years, studies designed to determine the real incidence and characteristics of PDPH in patients with migraines have not found evidence in favour of a higher incidence of PDPH in this migraine patient group.15 In our patient cohort, 58.3% of the patients who presented PDPH had a history of headache versus 41.7% in the group without PDPH. In this study we placed particular emphasis on identifying migraine features in the patients’ headache history; however, we did not find statistically significant differences in this sense. Nevertheless, when analysing headache intensity, we found greater PDPH intensity in the patient group with headaches associated with migraine characteristics.

Our series displayed greater PDPH intensity in the patient group with a medical history of migraine-style headaches. We observed extensive variability in terms or PDPH duration and intensity in the patient sample analysed.

One of the aspects we aimed to take into account with this study was the analysis of not only PDPH incidence, but also its intensity and duration, particularly due to the potential degree of impairment it can represent in certain instances. Van Oosterhout et al.15 identified the following as predictive factors for longer PDPH duration: sitting position during procedure, history of depression, need for multiple lumbar puncture attempts, and a high level of stress prior to the procedure. Regarding the intensity of the PDPH, we have not found any studies that have had a bearing on this aspect. Based on our findings, we can suggest a possible relationship between female sex, younger age, and a history of migraine headaches with higher intensity PDPH; however, in order to confirm this connection, a study with a larger sample size would need to be performed to provide results with solid evidence.

Following our analysis, professional experience was not related to the onset of PDPH, nor was the presence of cardiovascular risk factors. The vast majority of lumbar punctures were performed with a conventional 20 G needle considering it is the most available and is more convenient from a technical perspective. Nevertheless, a low incidence of PDPH has been reported with the use of conventional 22 G needles, and even lower incidence with atraumatic needle use.11,12 In the cited series,12 there was a 22.4% incidence of PDPH in the conventional needle group versus 8.5% in the atraumatic needle group, in addition to a shorter headache duration for this latter group. However, it must also be pointed out that there was a higher rate of failed attempts in the atraumatic needle group, with 19.5% of the cases requiring reassignment to the conventional needle group. In our setting, the main reason behind continuing to use conventional needles is the limited availability of atraumatic needles, the technical difficulty when using them and, in our opinion, the lack of technical knowledge of neurology staff. Implementing an educational and training program on this technique may be of interest in order to implement their use into regular clinical practice.

This study is prospective in design, with the main determinant for patient inclusion being medical care activity in the neurology department, specifically outpatient activity. At the time of patient recruitment, our primary limitation for the study was a significant period of interruption to in-person medical care due to the SARS-Covid-19 pandemic during the 2020−21 period. Therefore, one of the principal study limitations we can identify is the small sample size analysed. However, despite this limitation in the obtained results, we believe that a wide range of variables were recorded, including LP-related aspects not addressed in other studies.

ConclusionsThe incidence of PDPH in our series is 38.6%, though incidence varies greatly among the published series. The principal predisposing factors identified are young age and a medical history of headache. Other factors that we thought a priori could influence the onset of PDPH, such as BMI, biochemical CSF characteristics, or the experience of the professional performing the LP, were not found. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the various factors related to not only incidence, but also the intensity and duration of PDPH, in order to better inform patients and prevent PDPH.

FundingFunding for open access charge: Universidad de Granada / CBUA.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the nursing staff at hospital de día del Hospital Clínico Universitario San Cecilio de Granada.