To analyze the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and bronchial asthma on therapeutic management and prognosis of patients with heart failure (HF).

MethodsAnalysis of the information collected in a clinical registry of patients referred to a specialized HF unit from January-2010 to June-2012. Clinical profile, treatment and prognosis of patients was evaluated, according to the presence of COPD or asthma. Survival analyses were conducted by means of Kaplan-Meier and Cox’s methods. Median follow-up was 1493 days.

ResultsWe studied 2577 patients, of which 251 (9.7%) presented COPD and 96 (3.7%) bronchial asthma. Significant differences among study groups were observed regarding to the prescription of beta-blockers (COPD=89.6%; asthma=87.5%; no bronchopathy=94.1%; p=0.002) and SGLT2 inhibitors (COPD=35.1%; asthma=50%; no bronchopathy=38.3%; p=0.036). Also, patients with bronchial disease received less frequently a defibrillator (COPD=20.3%; asthma=20.8%; no broncopathy=29%; p=0.004).

COPD was independently associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR=1.64; 95% CI 1.33–2.02), all-cause death or HF admission (HR=1.47; 95% CI 1.22–1.76) and cardiovascular death or heart transplantation (HR=1.39; 95% CI 1.08–1.79) as compared with patients with no bronchopathy. Bronchial asthma was not significantly associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes.

ConclusionsCOPD, but not asthma, is an adverse independent prognostic factor in patients with HF.

Analizar el impacto de la enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) y el asma bronquial sobre el manejo terapéutico y el pronóstico de los pacientes con insuficiencia cardiaca (IC).

MétodosAnálisis de la información contenida en un registro clínico de pacientes remitidos a una unidad especializada de IC entre enero de 2010 y junio de 2022. Se comparó su perfil clínico, tratamiento y pronóstico en base a la presencia de EPOC o asma bronquial. El análisis de supervivencia se realizó mediante los métodos de Kaplan-Meier y Cox. La mediana de seguimiento fue de 1493 días.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 2577 pacientes, de los cuales 251 (9,7%) presentaban EPOC y 96 (3,7%) asma bronquial. Observamos diferencias significativas entre los tres grupos con respecto a la prescripción de betabloqueantes (EPOC=89,6%; asma=87,5%; no broncopatía=94,1%; p=0,002) e inhibidores del cotransportador de sodio-glucosa tipo 2 (EPOC=35,1%; asma=50%; no broncopatía=38,3%; p=0,036). Además, los pacientes con patología bronquial recibieron con menor frecuencia un desfibrilador (EPOC=20,3%; asma=20,8%; no broncopatía=29%; p=0,004).

La presencia de EPOC se asoció de forma independiente con mayor riesgo de muerte por cualquier causa (HR=1,64; IC 95% 1,33–2,02), muerte u hospitalización por IC (HR=1,47; IC 95% 1,22–1,76) y muerte cardiovascular o trasplante cardiaco (HR=1,39; IC 95% 1,08–1,79) en comparación con la ausencia de broncopatía. La presencia de asma bronquial no se asoció a un impacto significativo sobre los desenlaces analizados.

ConclusionesLa EPOC, pero no el asma bronquial, es un factor pronóstico adverso e independiente en pacientes con IC.

Article

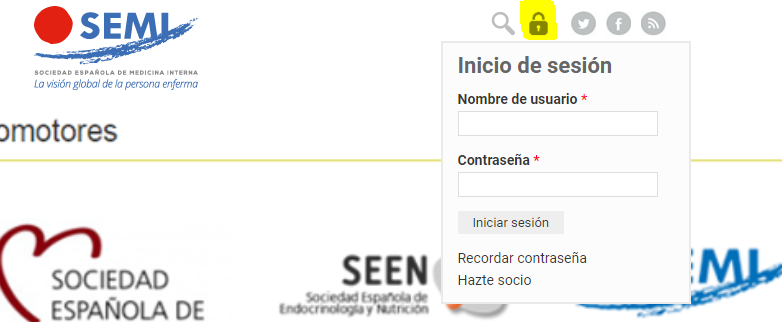

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<