The relationship between depression and diabetes has been widely documented but there have been methodological limitations such as the failure to conduct a diagnostic interview of the depressive condition. We have estimated the prevalence of depression in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) and its relationship with sociodemographic, lifestyle and clinical variables.

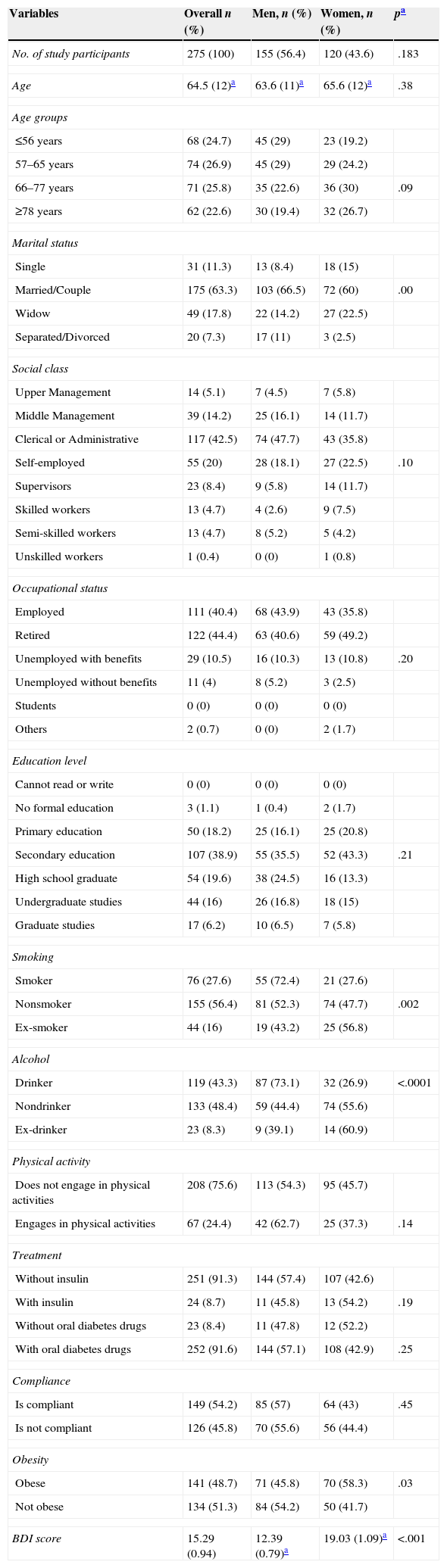

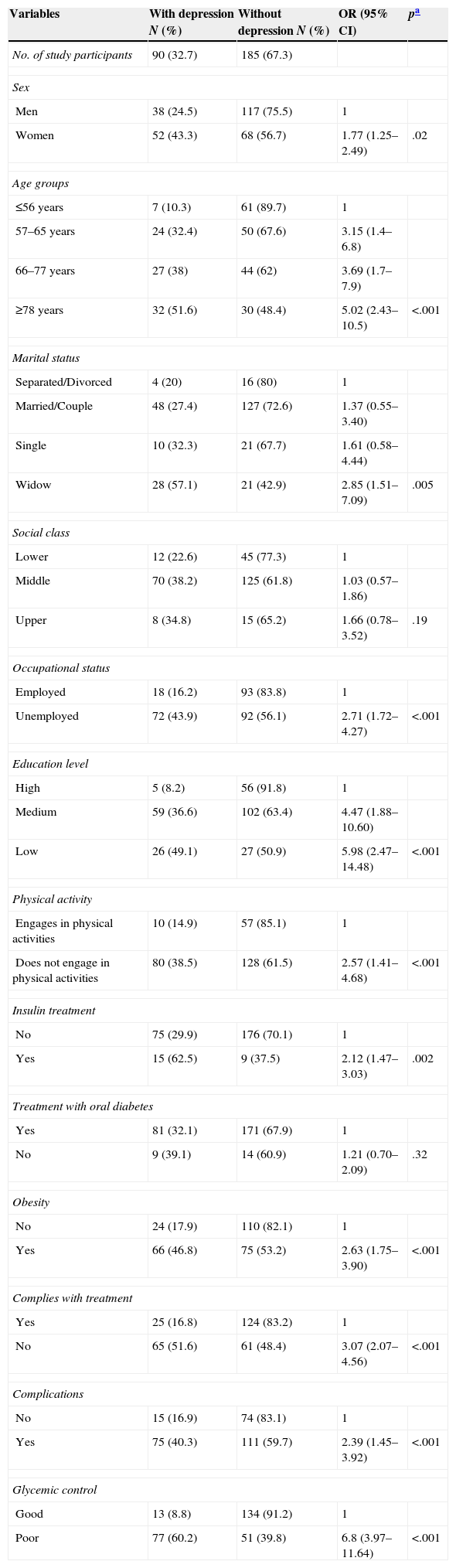

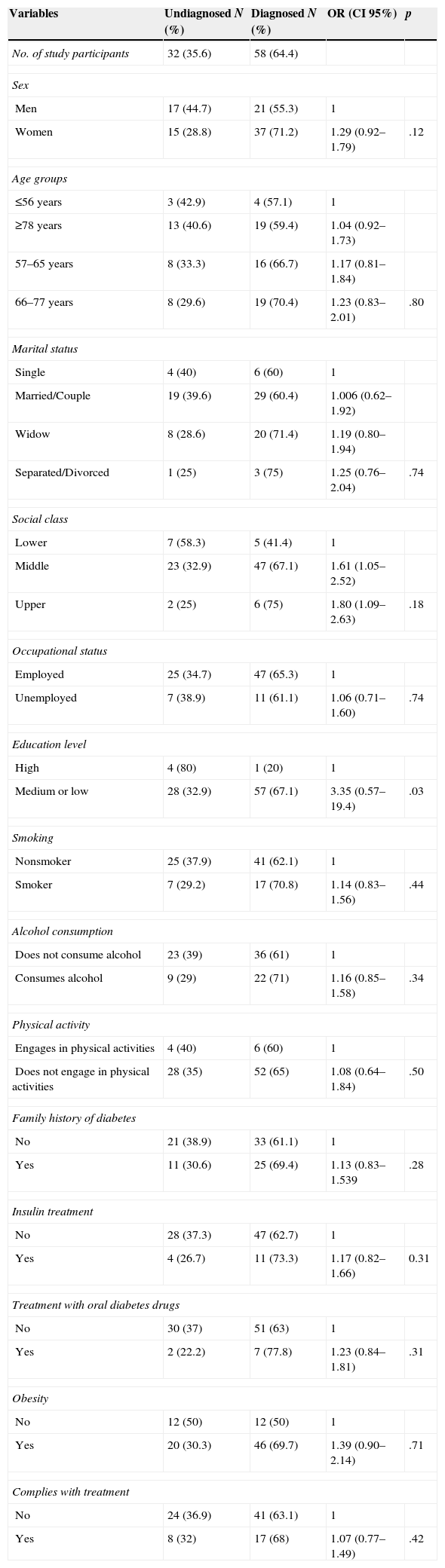

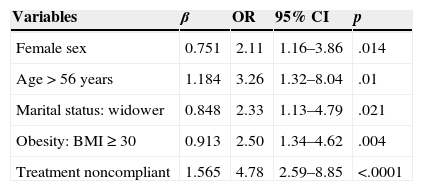

Patients and methodsThis was a cross-sectional, randomized study (stratified by sex and age) of patients with DM2 treated in a healthcare area with approximately 3000 eligible patients. The depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (depression defined as a BDI score ≥16) and a psychiatric interview. We used a multivariate logistic regression model to evaluate the association between depression and DM2, after adjusting for known risk factors.

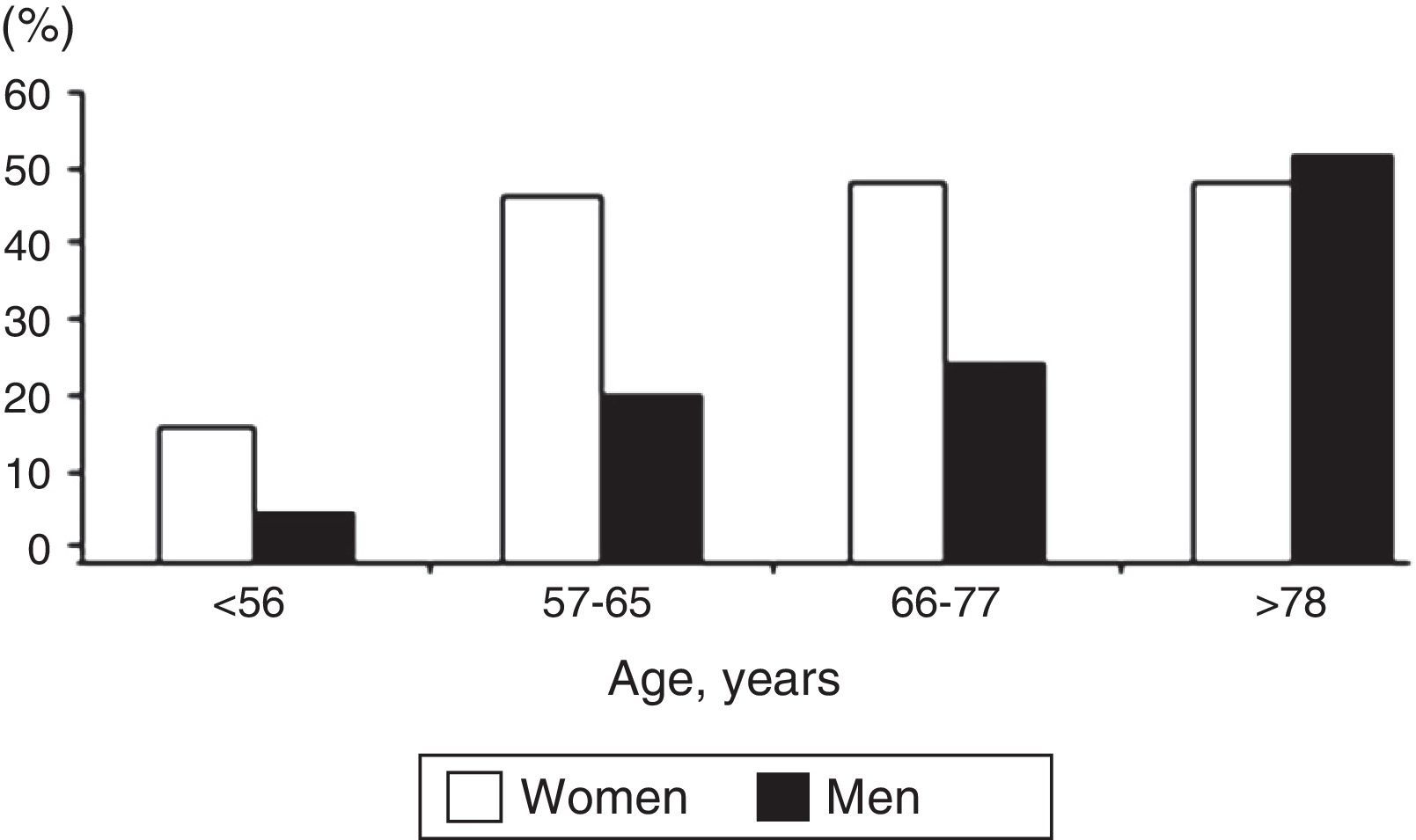

ResultsWe examined 275 patients with DM2 (mean age, 64.5 years; men, 56.4%). The prevalence of depression was calculated at 32.7% (95% CI 27.4–38.5) and increased with age. A greater prevalence of depression was found in women, widowers, patients with obesity, those with poor compliance with the prescription, those with poor glycemic control and those who developed complications from diabetes. Thirty-five percent (95% CI 26.4–45.8) of the patients who scored ≥16 on the BDI scale had not been diagnosed with depression.

ConclusionsDepression is highly prevalent in patients with DM2, especially in women. For approximately one-third of the patients, a diagnosis of depression had not been reached.

La relación entre depresión y diabetes ha sido ampliamente documentada pero con limitaciones metodológicas como la no realización de una entrevista diagnóstica del cuadro depresivo. Hemos estimado la prevalencia de depresión en pacientes con diabetes tipo 2 (DM2) y su relación con variables sociodemográficas, estilos de vida y clínicas.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio transversal, de una muestra aleatoria, estratificada por sexo y edad, de pacientes con DM2 atendidos en un área sanitaria con unos 3.000 enfermos elegibles. Los síntomas depresivos fueron evaluados mediante el Inventario de Depresión de Beck (depresión definida como BDI ≥16) y una entrevista psiquiátrica. Se utilizó un modelo de regresión logística multivariante para evaluar la asociación de la depresión con la DM2, tras ajustar por factores de riesgo conocidos.

ResultadosEstudiamos a 275 enfermos con DM2 (edad media: 64,5 años; hombres: 56,4%). La prevalencia de depresión se estimó en un 32,7% (IC 95%: 27,4–38,5) y aumentaba con la edad. Se encontró una mayor prevalencia en mujeres, en viudos, en obesos, en los malos cumplidores de la prescripción, en los que no mantenían un buen control glucémico y en los que habían desarrollado complicaciones de la diabetes. El 35% (IC 95%: 26,4–45,8) de los pacientes que obtuvieron una puntuación en la escala BDI≥16 no habían sido diagnosticados de depresión.

ConclusionesLa depresión es muy prevalente en los pacientes con DM2, especialmente en mujeres. En cerca de un tercio de los enfermos, el diagnóstico de depresión no se había formulado.

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<