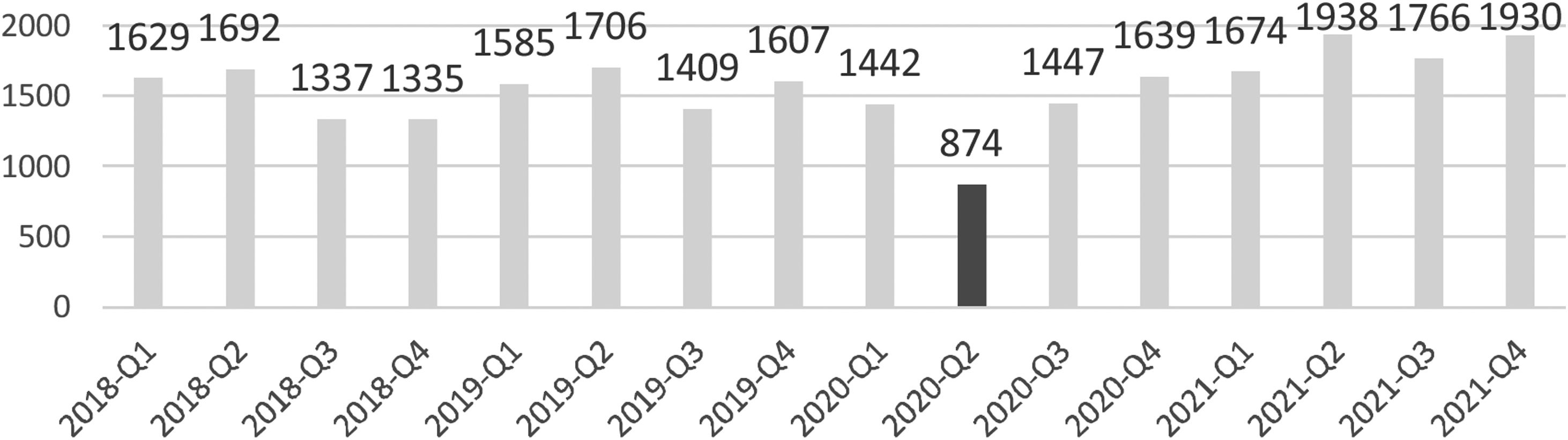

Virtual healthcare models, usually between healthcare professionals and patients, have developed strongly during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, but there are no data corresponding to models between clinicians. An analysis was made of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon the activity and health outcomes of the universal e-consultation program for patient referrals between primary care physicians and the Cardiology Department in our healthcare area.

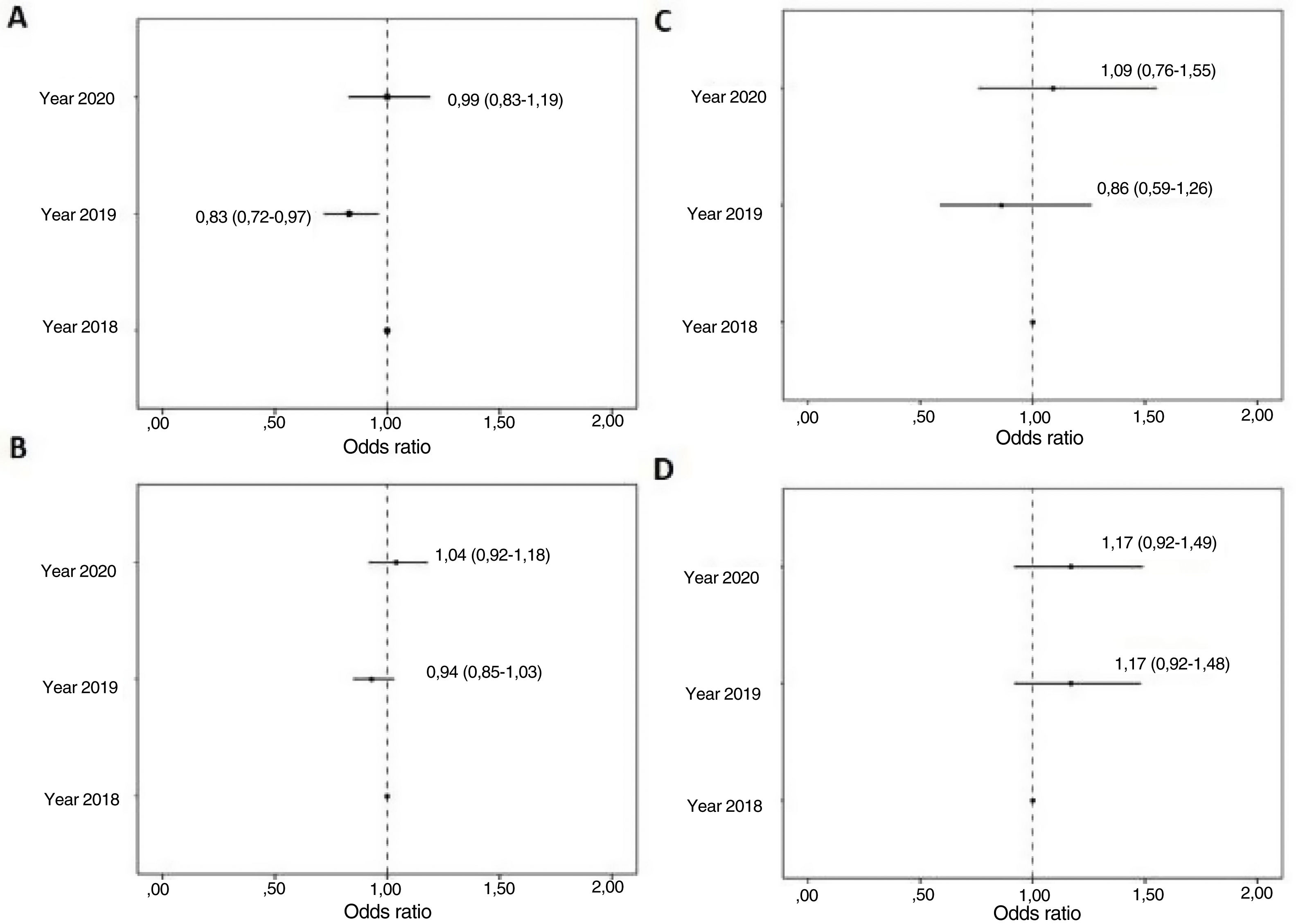

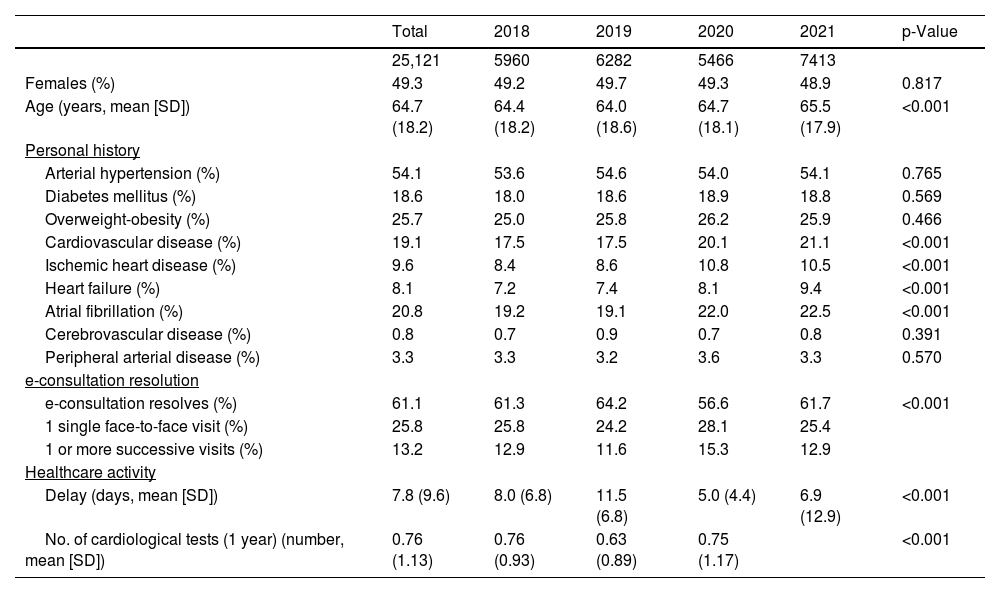

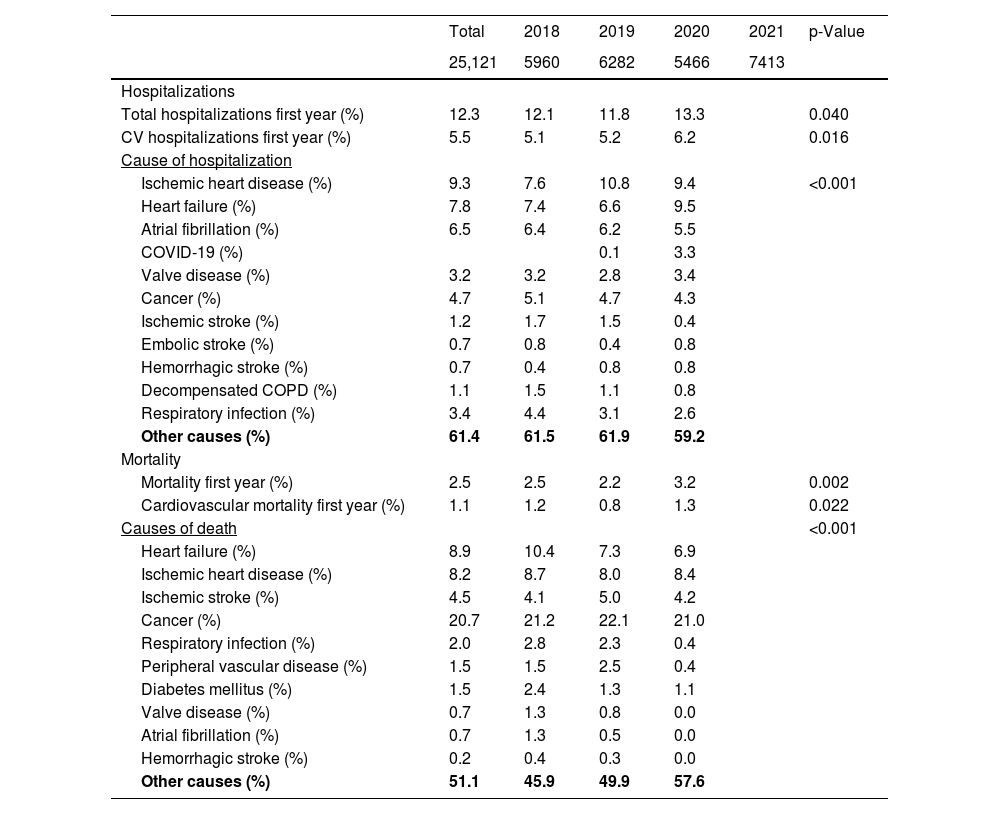

MethodsPatients with at least one e-consultation between 2018 and 2021 were selected. We analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon activity and waiting time for care, hospitalizations and mortality, taking as reference the consultations carried out during 2018.

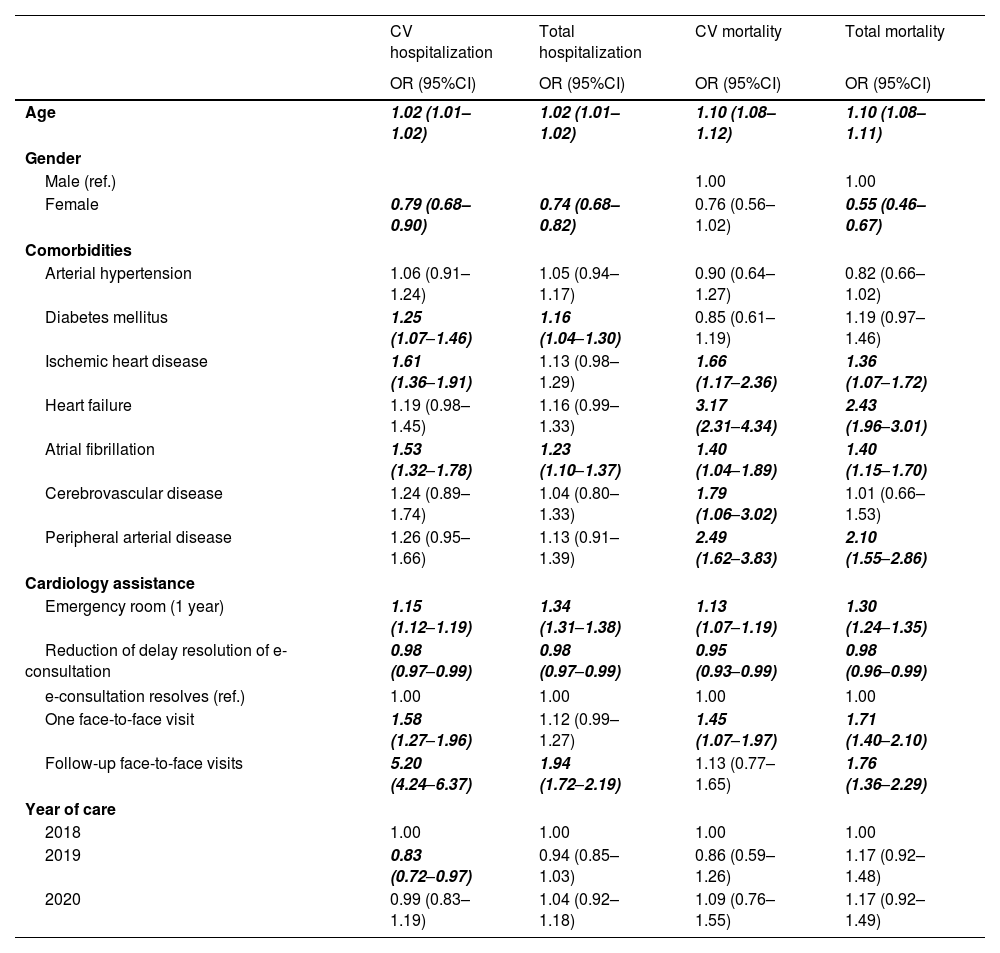

ResultsA total of 25,121 patients were analyzed. Logistic regression analysis showed a shorter delay in care and resolution of the e-consultation without the need for face-to-face care to be associated to a better prognosis. The COVID-19 pandemic periods (2019–2020 and 2020–2021) were not associated to poorer health outcomes compared to 2018.

ConclusionsThe results of our study show a significant reduction in e-consultation referrals during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a subsequent recovery in the demand for care, and without the pandemic periods being associated to poorer outcomes. The reduction in time elapsed for resolving the e-consultations and no need for face-to-face visits were associated to improved outcomes.

Los programas de telemedicina entre clínico y paciente se han desarrollado con fuerza durante la pandemia de enfermedad por COVID-19, pero no hay datos de experiencias entre clínicos. Nuestro objetivo es analizar el impacto de la pandemia por COVID-19 en la actividad y resultados en salud de un programa de consulta electrónica universal (e-consulta) para todas las derivaciones de pacientes entre médicos de atención primaria y el Servicio de Cardiología de nuestra área.

MétodosAnalizamos mediante regresión logística 25,121 pacientes con al menos una e-consulta entre 2018 y 2021 realizada con el Servicio de Cardiología de nuestra área sanitaria. También se realizó el análisis de regresión logística del impacto de la pandemia por COVID-19 sobre la resolución de la e-consulta y tiempo de espera de la atención, hospitalizaciones y mortalidad, tomando como referencia las consultas realizadas durante 2018.

ResultadosObservamos que una menor demora en la atención y resolución de la e-consulta (sin necesidad de atención presencial) se asociaba a un mejor pronóstico. Los períodos de pandemia COVID-19 presentaron similares resultados a los del 2018.

ConclusionesLos resultados de nuestro estudio muestran una significativa reducción de las derivaciones a través de e-consulta durante el primer año de la pandemia por COVID-19 con recuperación posterior de la demanda asistencial sin que los períodos de pandemia se asociasen con peores resultados en salud. La reducción del tiempo de demora de resolución de la e-consulta y el grupo sin necesidad de consulta presencial se asociaron a un mejor pronóstico.

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<