Prevalence studies of acid sphingomyelinase deficiency (ASMD) are scarce and different in Spain. The objective of the present study was to determine the estimated prevalence of patients diagnosed with ASMD (types A/B and B) in Spain.

Material and methodsPREVASMD was a descriptive, multicenter, and ecological study involving 21 physicians from different specialties (mainly Internal Medicine, Paediatrics and Hematology), of different autonomous communities, with experience in ASMD management.

ResultsBetween March and April 2022, specialists were attending a total of 34 patients with ASMD diagnosis, 10 paediatric patients under 18 years of age (29.4%) and 24 adult patients (70.6%). The estimated prevalence of patients (paediatric and adult) diagnosed with ASMD was 0.7 per 1,000,000 inhabitants (95% confidence interval, 95% CI: 0.5-1.0), 1.2 per 1,000,000 (95% CI: 0.6–2.3) in the paediatric population and 0.6 per 1,000,000 inhabitants (95% CI: 0.4–0.9) in the adult population. The most frequent symptoms that led to suspicion of ASMD were: splenomegaly (reported by 100.0% of specialists), hepatomegaly (66.7%), interstitial lung disease (57.1%), and thrombocytopenia (57.1%). According to the specialists, laboratory and routine tests, and assistance in Primary Care were the most relevant healthcare resources in the management of ASMD.

ConclusionsThis first study carried out in Spain shows an estimated prevalence of patients of 0.7 per 1,000,000 inhabitants: 1.2 per 1,000,000 inhabitants in the paediatric population and 0.6 per 1,000,000 inhabitants in the adult population.

Los estudios de prevalencia del déficit de esfingomielinasa ácida (ASMD) son escasos y dispares en España. El objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar la prevalencia estimada de pacientes diagnosticados de ASMD (tipos A/B y B) en España.

Material y métodosPREVASMD fue un estudio descriptivo, multicéntrico y ecológico en el que participaron 21 médicos de diferentes especialidades (principalmente de Medicina Interna, Pediatría y Hematología), de distintas comunidades autónomas, con experiencia en el manejo del ASMD.

ResultadosEntre marzo y abril de 2022, los especialistas estaban atendiendo a un total de 34 pacientes con diagnóstico del ASMD, 10 pacientes pediátricos menores de 18 años (29,4%) y 24 pacientes adultos (70,6%). La prevalencia estimada de pacientes (pediátricos y adultos) diagnosticados con ASMD era 0,7 por 1.000.000 de habitantes (intervalo de confianza 95%, IC 95%: 0,5-1,0), 1,2 por 1.000.000 (IC 95%: 0,6-2,3) en población pediátrica y 0,6 por 1.000.000 de habitantes (IC 95%: 0,4-0,9) en población adulta. Los síntomas más frecuentes que llevaron a la sospecha del ASMD fueron: esplenomegalia (informada por el 100,0% de los especialistas), hepatomegalia (66,7%), enfermedad pulmonar intersticial (57,1%) y trombocitopenia (57,1%). Según los especialistas, las pruebas de laboratorio y rutinarias, y la asistencia en Atención Primaria fueron los recursos sanitarios más relevantes en el manejo del ASMD.

ConclusionesEste primer estudio realizado en España muestra una prevalencia estimada de pacientes de 0,7 por 1.000.000 de habitantes: 1,2 por 1.000.000 de habitantes en población pediátrica y 0,6 por 1.000.000 de habitantes en población adulta.

Acid sphingomyelinase deficiency (ASMD), previously known as Niemann-Pick A or B (or simply NPD), is an extremely rare lysosomal disease that is characterised by the accumulation of sphingomyelinase, mainly in hepatocytes and reticuloendothelial system cells.1 The most frequently affected organs are the liver, spleen, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes, as well as the central nervous system in more severe cases.2,3

ASMD is a disease that remains largely unknown, that presents a wide range of different and non-specific symptoms, making it difficult to diagnosis and often resulting in a delayed diagnosis that can take many years.4,5 Although the clinical presentation is non-specific, ASMD may be suspected in patients with hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, interstitial lung disease, hyperlipidaemia, delayed development, and/or a cherry-red spot on the ocular fundus (particularly in pediatric patients). Diagnosis can be confirmed by means of biochemical and genetic techniques. The gold standard diagnostic technique is to measure enzyme acid sphingomyelinase activity in dried blood spots that can be performed in peripheral blood lymphocytes or in cultured skin fibroblasts.6 Following a positive enzymatic diagnosis it is recommended to complement this confirmation with a genetic study to detect pathogenic mutations of the SMPD1 gene.6,7

The progression of the disease varies from the fast-progressing and fatal forms presenting in children to the chronic, slower progressing form presenting in adults.8 ASMD has different phenotypes: ASMD type A, infantile neurovisceral; ASMD type B, chronic visceral; and ASMD type A/B, chronic neurovisceral.9 Types A and A/B are associated with neurological involvement. Type A has a highly uniform natural history, characterised by hepatosplenomegaly at 2 to 4 months old and progressive neurodegeneration starting in the first months of life and an expected survival of less than 3 years.9 The most common form of the disease is ASMD type B and does not present with neurological involvement (or if it does it is very mild); it is the most variable form of the disease, both in terms of clinical presentation and life expectancy, which can reach 70 years or result in premature death due to related complications. The visceral manifestations are clearly predominant in this phenotype.9

Studies on ASMD prevalence are few and provide varied data (between 0.3 and 0.6 cases per every 100,000 or 250,000 live births).10–14 Recently, consensus clinical guidelines for the management of ASMD have presented a prevalence of approximately 1 out of 100,000 or 1,000,000 births.1 To date, no epidemiological studies have been carried out in patients with this disease in Spain. Therefore, the main objective of the present study was to determine the estimated prevalence of patients diagnosed with ASMD (types A/B and B) in Spain.

MethodsStudy designPREVASMD was a descriptive, multicentre, and ecological study involving 21 physicians from different specialties and diverse autonomous communities in Spain, with experience in ASMD management. The data source was the experience of specialised physicians collected by means of a questionnaire designed for this purpose. The study’s approach was based on the analysis of the population as a whole (aggregated data). Therefore, none of the data were collected from medical chart or individual patient information. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal in Madrid.

Study variables and questionnaireThe primary variable was the estimated prevalence of patients (paediatrics and adults) diagnosed with ASMD, type A/B and B, out of the total number of patients attended by the participating specialists. Other secondary variables included describing the sociodemographic and clinical profile of these patients and the burden of the disease on the healthcare system. The questionnaire consisted of 29 questions aimed at obtaining information about the primary objective. Thus, aggregated data were obtained from patients with ASMD (type A/B and B) who attended the healthcare professional's consultations with the characteristics defined in each section of the questionnaire. Additionally, some specific questions regarding the aforementioned secondary study objectives were also included. The questionnaire can be found in the Supplementary material.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis involved a descriptive analysis of the questionnaire responses. Quantitative variables are shown as mean and standard deviation (SD), whereas qualitative ones as absolute and relative frequencies. Lost data were not taken into consideration for the analysis. To calculate the prevalence, the total population data of Spain provided by the National Institute of Statistics was used as of 1 January, 2022 (47,432,805 as total population, 39,295,441 as adult population, and 8,137,364 as paediatric population aged 0 to 17 years).15 The mean weight was estimated using the weighted average of the median of patient weight ranges presented by the specialists. All the analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsParticipating specialistsBetween March and Abril 2022, a total of 21 specialists from 9 autonomous communities participated. The list of autonomous communities can be found in the Supplementary Table 1. The specialists had a mean clinical experience of 17.6 years (SD: 8.4). The specialties included Internal Medicine (38.1%), Paediatrics (28.6%), Haematology (23.8%), Gastroenterology (4.8%), and the Metabolic Unit (4.8%).

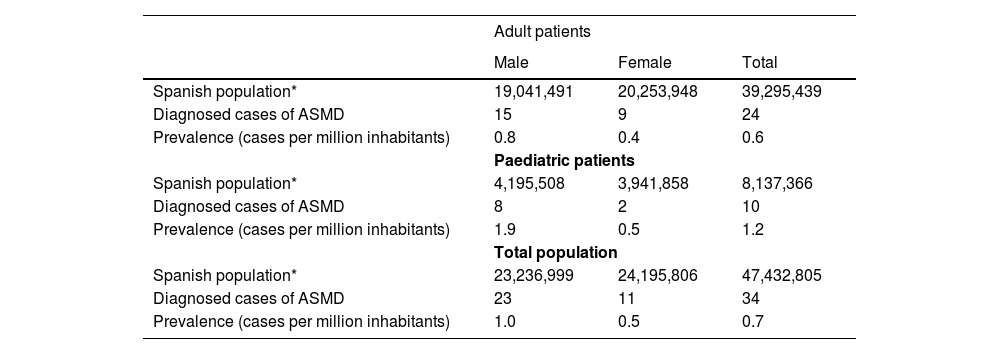

ASMD prevalence in SpainThe specialists were attending a total of 34 patients with diagnosis of ASMD, 10 paediatric patients under 18 years of age (29.4%) and 24 adult patients aged 18 years or over (70.6%). The estimated prevalence of patients (paediatrics and adults) diagnosed with ASMD was 0.7 per 1,000,000 inhabitants (95% confidence interval, 95% CI: 0.5–1.0), for the total population, 1.2 per 1,000,000 inhabitants (95% CI: 0.6–2.3) in paediatric population and 0.6 per 1,000,000 inhabitants (95% CI: 0.4–0.9) in adult population (Table 1). The estimated prevalence of ASMD (types A/B and B) in the autonomous communities where the cases were identified are shown in the Supplementary Figure 1.

Estimated prevalence of ASMD in Spain.

| Adult patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | |

| Spanish population* | 19,041,491 | 20,253,948 | 39,295,439 |

| Diagnosed cases of ASMD | 15 | 9 | 24 |

| Prevalence (cases per million inhabitants) | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Paediatric patients | |||

| Spanish population* | 4,195,508 | 3,941,858 | 8,137,366 |

| Diagnosed cases of ASMD | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Prevalence (cases per million inhabitants) | 1.9 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| Total population | |||

| Spanish population* | 23,236,999 | 24,195,806 | 47,432,805 |

| Diagnosed cases of ASMD | 23 | 11 | 34 |

| Prevalence (cases per million inhabitants) | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

ASMD, acid sphingomyelinase deficiency.

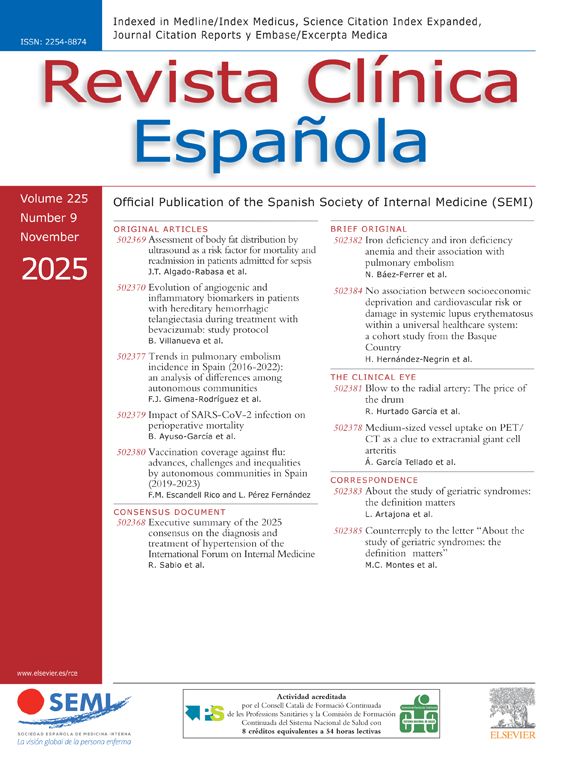

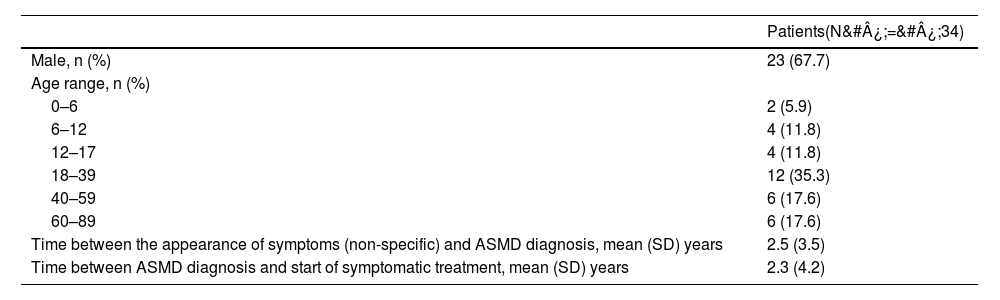

The majority of patients with ASMD diagnosis were male (67.7%) and adults (70.6%). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with ASMD diagnosis are shown in Table 2. The estimated mean weight of paediatric patients (<18 years) was 29.4&#¿;kg, and that of adults (≥18 years) was 70.5&#¿;kg. The mean time elapsed between the appearance of symptoms (non-specific) and ASMD diagnosis was 2.5 years (SD: 3.5), and from diagnosis to the start of symptomatic treatment was 2.3 years (SD: 4.2). The most frequently presented symptoms among patients with ASMD were: splenomegaly (reported by 90.5% of specialists), hyperlipidaemia (66.7%), interstitial lung disease (57.1%), hepatomegaly (57.1%), and thrombocytopenia (52.4%). Of these symptoms, those that led specialists to suspect of ASMD were: splenomegaly (100.0%), hepatomegaly (66.7%), interstitial lung disease (57.1%), and thrombocytopenia (57.1%; Fig. 1A). According to the specialists, the prognosis and disease progression was mainly determined by the severity of lung involvement (100.0% of them; available n&#¿;=&#¿;21), followed by the severity of the liver involvement (81.0%), the patient’s age (52.4%), residual enzyme activity (52.4%), and genetic factors (42.9%; Fig. 1B).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with ASMD diagnosis (according to the participating specialists).

| Patients(N&#¿;=&#¿;34) | |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 23 (67.7) |

| Age range, n (%) | |

| 0–6 | 2 (5.9) |

| 6–12 | 4 (11.8) |

| 12–17 | 4 (11.8) |

| 18–39 | 12 (35.3) |

| 40–59 | 6 (17.6) |

| 60–89 | 6 (17.6) |

| Time between the appearance of symptoms (non-specific) and ASMD diagnosis, mean (SD) years | 2.5 (3.5) |

| Time between ASMD diagnosis and start of symptomatic treatment, mean (SD) years | 2.3 (4.2) |

ASMD: acid sphingomyelinase deficiency; SD: standard deviation.

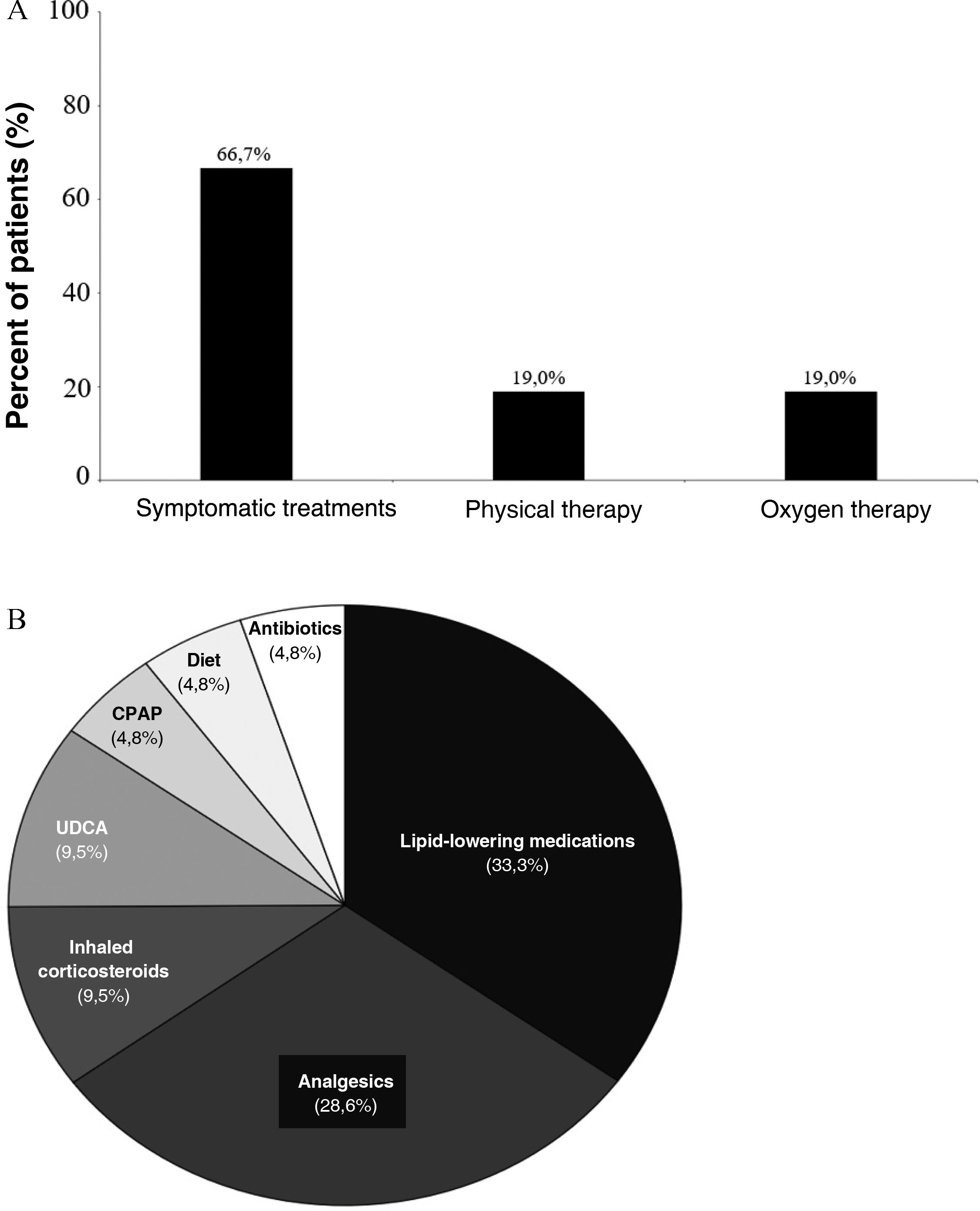

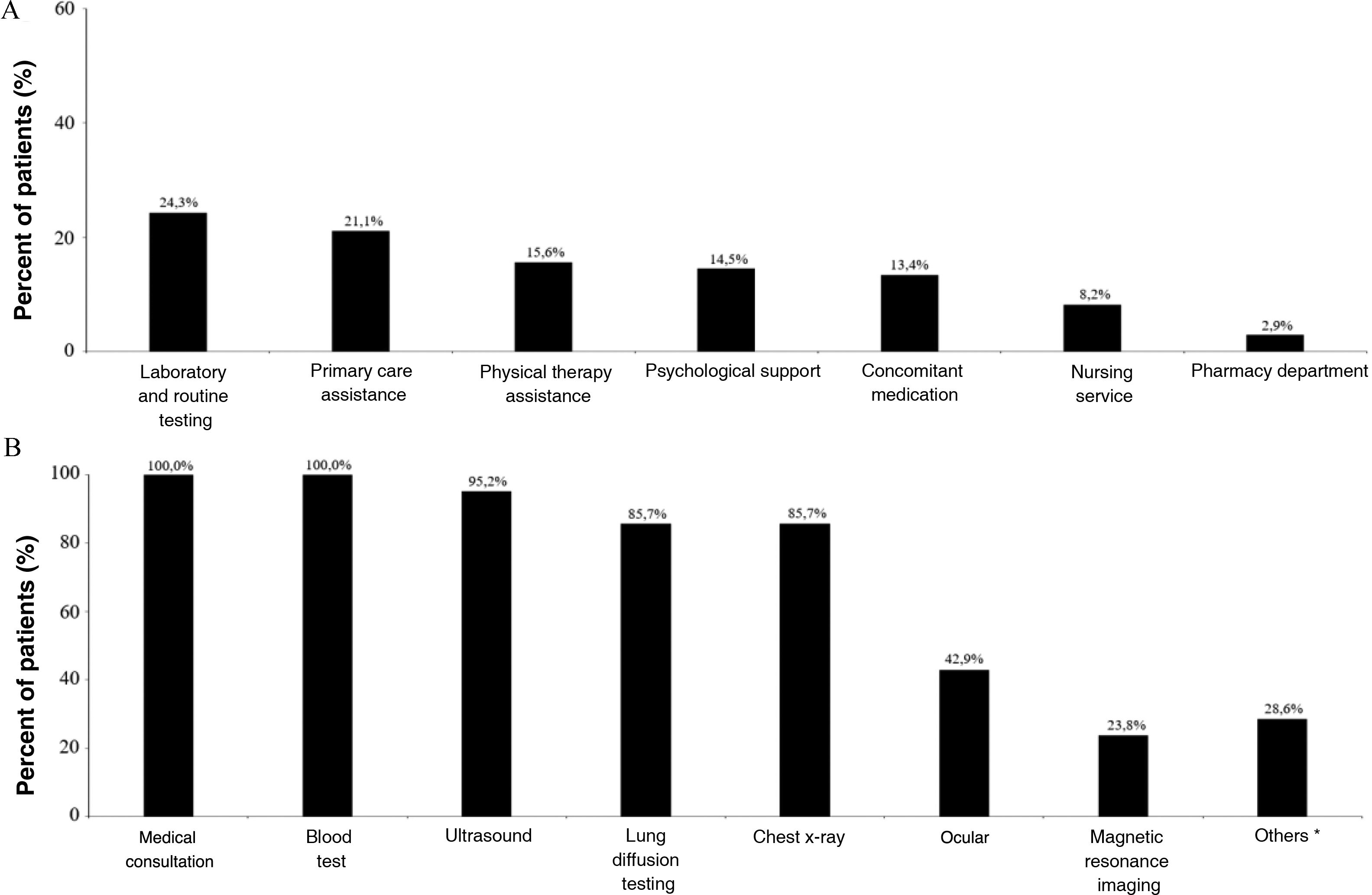

In the absence of an enzymatic treatment (approved by the European Medicines Agency but not priced in Spain), according to the specialists, 66.7% of patients were receiving symptomatic treatments, 19.0% physical therapy, and 19.0% oxygen therapy (Fig. 2A). The most common symptomatic treatments were lipid-lowering agents (33.3%) and painkillers (28.6%; Fig. 2B). A total of 76.2% of the specialists reported having ordered enzymatic/genetic testing to diagnose the disease. For cases in which enzymatic/genetic testing were not ordered, diagnosis was made by correlating family history, compatible/highly suggestive clinical presentation of the disease, or histological studies (especially bone marrow biopsy), while awaiting the enzymatic and genetic results. According to the specialists, the most important healthcare resources used in the management of ASMD were laboratory and routine testing (24.3%) and Primary Care assistance (21.1%; Fig. 3A). The specialists indicated that they primarily used the medical consultation (100.0% of them), blood tests (100.0%), ultrasound (95.2%), lung diffusion testing (85.7%), and chest X-rays (85.7%) for the patient follow-up (Fig. 3B). A total of 19.0% of the specialists reported that their patients were hospitalised once a year, on average. Main reasons for hospitalisation in patients with ASMD were respiratory failure (38.1%), pneumonia (23.8%), and liver failure (9.5%). A total of 28.6% of the specialists stated that their patients had visited the Emergency Department due to their disease between one and four times during the past year. Lastly, they pointed out that none of their patients required a surgical intervention.

Most commonly used health care resources (A) and routine testing and clinical follow-up (B) in patients with ASMD diagnosis.

ASMD: acid sphingomyelinase deficiency.

*Others include bone densitometry, polysomnography, lung MRI, chest MRI, echocardiography, spirometry, and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide.

This is the first epidemiological study of ASMD in Spain and reports an estimated prevalence of 0.7 cases per 1,000,000 inhabitants, that is higher in the paediatric population (1.2) than in adult population (0.6). Previous studies carried out in different countries (Czech Republic, The Netherlands, Portugal, and United Arab Emirates) have shown prevalence rates of ASMD types A and B at birth of between 0.3 and 0.6 cases for every 100,000 live births.11–14 However, a prior study from Australia reported a rate of 1 in every 248,000 live births.10 In our study, the prevalence of ASMD types A/B and B measured in paediatric and adult populations is below that reported in previously published studies.4 In our opinion, methodological disparities in determining the prevalence might explain these discrepancies. On the one hand, previous studies evaluated prevalence at birth; thus, calculations were made based on the total number of diagnosed cases that were born during a certain time frame with respect to the total number of births in that same period. Furthermore, these studies determined the combined prevalence of ASMD types A and B, unlike our study which considered types A/B and B. In any case, all estimated prevalence rates, those from both the literature11–14 and our study, were based on suspected cases that were referred by specialists for the biochemical and/or molecular confirmation, and not based on screening studies of the general population. The only available screening study was carried out in Chile on 1,691 healthy individuals, where one of the pathogenic variants of ASMD (p.Ala359Asp) was identified.16 That study reported a disease incidence of 1 case per 44,960 individuals. Given the limited available information, it is considered that ASMD is highly underdiagnosed in routine clinical practice, especially in cases of ASMD type B where the diagnosis may not be easily evident.

In that regard, the clinical manifestations of ASMD may overlap with other lysosomal storage disorders such as Gaucher’s disease.10 Hepatosplenomegaly is one of the most common clinical manifestations used for identification.17 The presence of interstitial lung disease and dyslipidaemia may help differentiate ASMD from other pathologies such as hematologic malignancies that can also present with hepatosplenomegaly and pancytopenia.10 Nevertheless, definitive diagnostic confirmation of ASMD is achieved using biochemical and/or genetic testing.18,19 In our study, the specialists identified splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, interstitial lung disease, and thrombocytopenia as the primary symptoms that lead to diagnosis. It is also important to highlight that the specialists associated the severity of lung and liver involvement as main factors for determining prognosis and the course of the disease. As described in prior studies, there is an important delay between the initial onset of symptoms and a definitive diagnosis of the disease (approximately 5 on average).20 In our study, the diagnostic delay was slightly lower (2.5 years). With regards to patients with ASMD, it must be stated that most of them in our study were adults (70.6%). By contrast, other studies have reported similar data or a majority of paediatric patients.20,21 For example, in one multinational, multicentre, cross-sectional survey study with data from 59 patients with ASMD type B, 50.8% of patients were paediatric.20 However, one study with data from 64 cases of ASMD type B showed that the percent of paediatric patients (57.8%) was slightly higher than that of adults (42.2%).21

In Spain, the PREDIGA project is currently being carried out with the aim of identifying undiagnosed patients with ASMD disease and Gaucher’s disease who could benefit from effective treatments.22 The project also involves a country-wide education program aimed at improving the knowledge on these diseases and the dissemination of diagnostic algorithms. During the first year of the educational project, with the participation of 52 healthcare professionals from 34 hospitals in Spain, 166 patients with diagnostic criteria were reviewed and diagnostic confirmation of ASMD was achieved in two of them.

On the other hand, ASMD is associated with a significant physical, emotional, psychosocial, and economic burden on patients and caregivers.23,24 Previous studies have revealed that patients with chronic diseases require outpatient care that includes physical therapy or home medical care. In addition, it has been reported that the use of healthcare services by patients with ASMD is extensive and may include laboratory testing (liver enzymes and lipid panels), pulmonary function testing, histopathology, ultrasound/X-rays, and pharmacological prophylactic and symptomatic treatments. They also require medical services such as oxygen therapy, physical therapy, and organ transplant.25,26 In our study, the most commonly used healthcare resources were laboratory tests and Primary Care consultations. For patient follow-up, specialists mainly used medical consultations, blood tests, ultrasounds, pulmonary diffusion tests, and chest X-rays.

The main limitation of the present study is the subjective nature of the data, which are provided as aggregated data from the specialists’ experience, i.e. without including data from medical charts. Also, data may be influenced by a recall bias. Despite that, ecological studies are part of epidemiological observational designs and are used as hypothesis generators as they are easy to carry out, quick, low-cost, and relatively easy to analyse.27 Another study limitation may derive from the 23.8% of patients with ASMD, whose diagnosis could not confirmed via genetic testing due to the closure of the database. Yet, algorithms used in clinical practice allow for an ASMD diagnosis to be established based on family history, clinical presentation highly suggestive of the disease, or histological studies. Overall, our results provide a first step of information on the epidemiology of the disease in Spain, as well as the sociodemographic and clinical profile of these patients and the burden of disease on the healthcare system.

ConclusionThis first study of ASMD carried out in Spain presents an estimated prevalence of patients with ASMD type A/B and B of 0.7 per 1,000,000 inhabitants, which is higher in paediatric population (1.2) than in adult population (0.6). Given the scarce epidemiological studies on this disease, it is considered to be underdiagnosed in routine clinical practice. More studies are needed with a larger number of participants and, even, screening studies in healthy population to establish a value as close to reality as possible.

FundingThis study was financed by Sanofi Spain. Assistance in the writing of the manuscript was provided by Evidenze Health España S.L.U., which was hired by Sanofi Spain. Sanofi Spain had no direct relationship with the authors. None of the authors received direct financing from the industry.

The list of participants in the PREVASMD study group also includes Beatriz Buno Ramilo (Hospital Arquitecto Marcide, A Coruña), Alejandro Contento (Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga), Iván Pérez de Pedro (Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga), Lucía Villalón Blanco (Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid), Cecilia Muñoz Delgado (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid), María del Carmen Mendoza Sánchez (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca), Antonio Gonzalez-Meneses (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla), Dolores Gómez Toboso (Hospital de Manises, Valencia), Moisés de Vicente (Hospital General Nuestra Señora del Prado, Toledo), Alicia Rodríguez (Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla), Jose Antonio Pérez de León (Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla) and Xavier Solanich (Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, Barcelona). All the authors have maintained editorial independence and independent opinions while preparing this manuscript.