Acute respiratory infection is a very common condition in the general population. The majority of these infections are due to viruses. This study attempted to determine the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of adult patients with respiratory infection by the coronavirus OC43, NL63 and 229E.

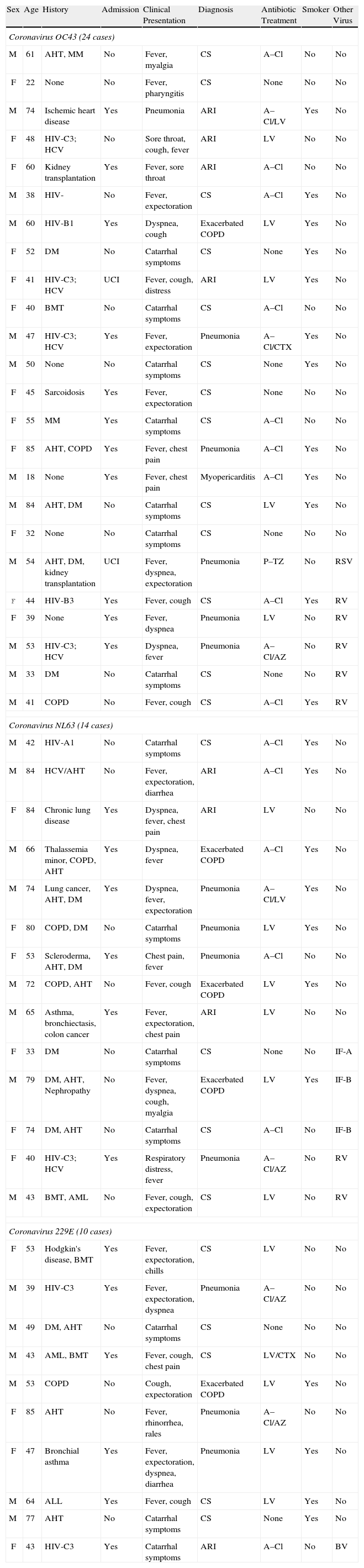

Patients and methodsBetween January 2013 and February 2014, we prospectively studied all patients with suspected clinical respiratory infection by taking throat swabs and performing a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in search of coronavirus.

ResultsIn 48 cases (7.0% of the 686 enrolled patients; 12.6% of the 381 in whom a virus was detected) the presence of a coronavirus demonstrated. In 24 cases, the virus was OC43 (50%); in 14 cases, the virus was NL63 (29%); and in 10 cases, the virus was 229E (21%). The mean age was 54.5 years, with a slight predominance of men. The most common clinical presentations were nonspecific influenza symptoms (43.7%), pneumonia (29.2%) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation (8.3%). Fifty-two percent of the patients required hospitalization, and 2 patients required intensive care. There were no deaths.

ConclusionAcute respiratory infections caused by coronavirus mainly affect middle-aged male smokers, who are often affected by previous diseases. The most common clinical picture has been nonspecific influenza symptoms.

Las infecciones respiratorias agudas son una entidad muy frecuente en la población general. La mayoría de ellas son debidas a infecciones víricas. Este estudio pretende precisar las características clínicas y epidemiológicas de los pacientes adultos con infección respiratoria por los coronavirus OC43, NL63 y 229E.

Pacientes y métodosEntre enero del 2013 y febrero del 2014 se estudió prospectivamente a todos los pacientes con sospecha clínica de infección respiratoria mediante la toma de un frotis faríngeo y la realización de una reacción en cadena de la polimerasa en transcripción reversa en tiempo real en búsqueda de coronavirus.

ResultadosEn 48 casos (7,0% de los 686 pacientes incluidos; 12,6% de los 381 en los que se detectó algún virus) se pudo demostrar la presencia de algún coronavirus. En 24 casos se trataba del OC43 (50%), en 14 del NL63 (29%) y en 10 del 229E (21%). La edad media fue de 54,5 años, con un ligero predominio de varones. Las presentaciones clínicas más frecuentes fueron el cuadro gripal inespecífico (43,7%), la neumonía (29,2%) y la agudización de enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (8,3%). El 52% de los pacientes precisaron ingreso hospitalario, en 2 ocasiones en cuidados intensivos. No se produjo ningún fallecimiento.

ConclusiónLas infecciones respiratorias agudas causadas por coronavirus inciden preferentemente en varones fumadores en la edad media de la vida, frecuentemente afectados de enfermedades previas. La sintomatología clínica mas frecuente ha sido el cuadro gripal inespecífico.

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<