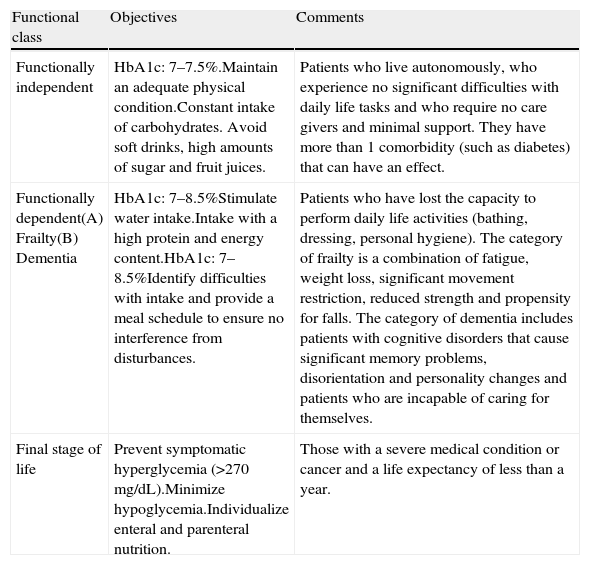

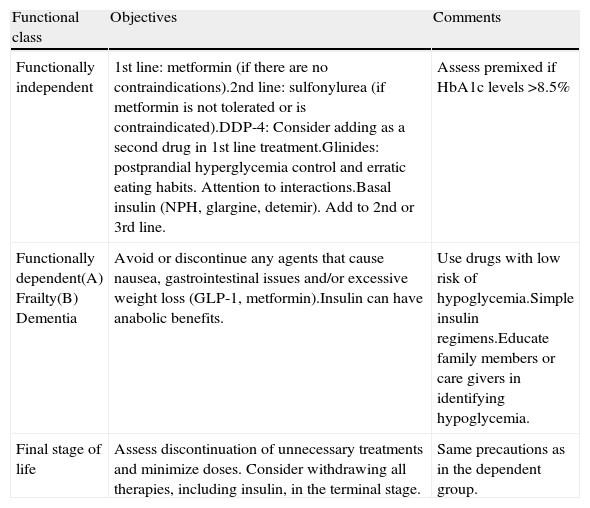

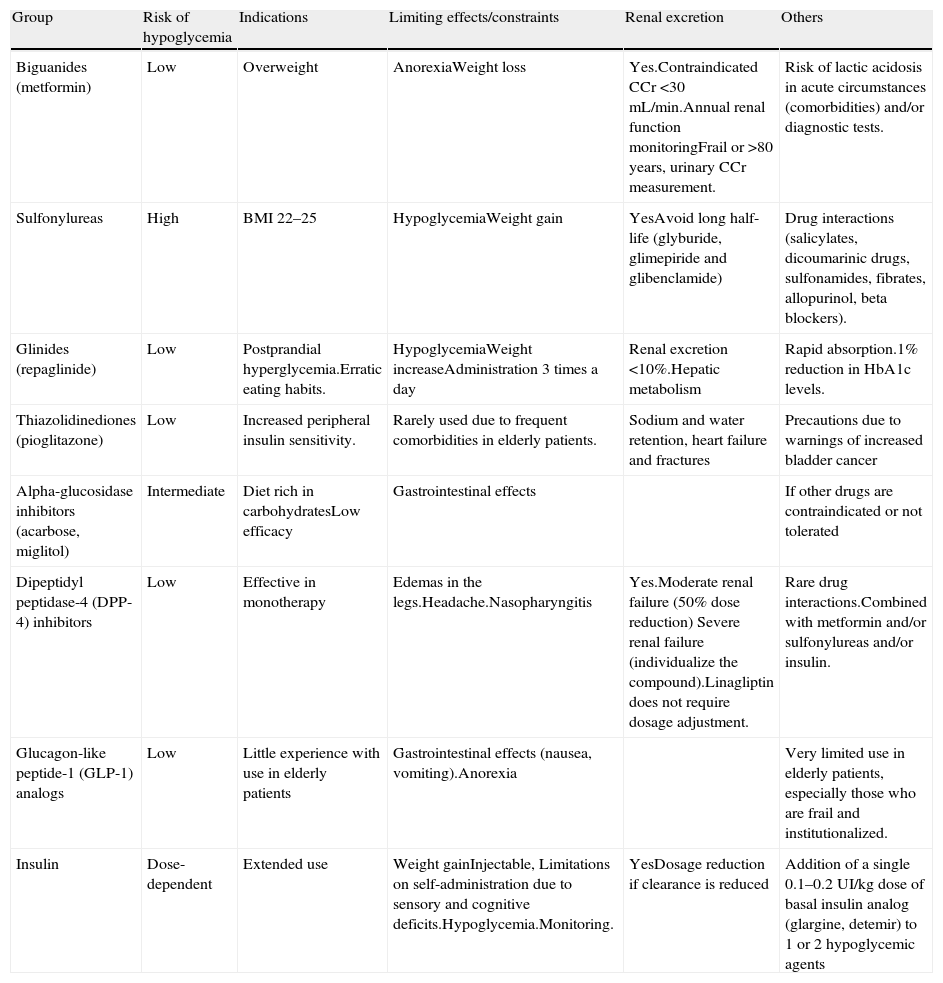

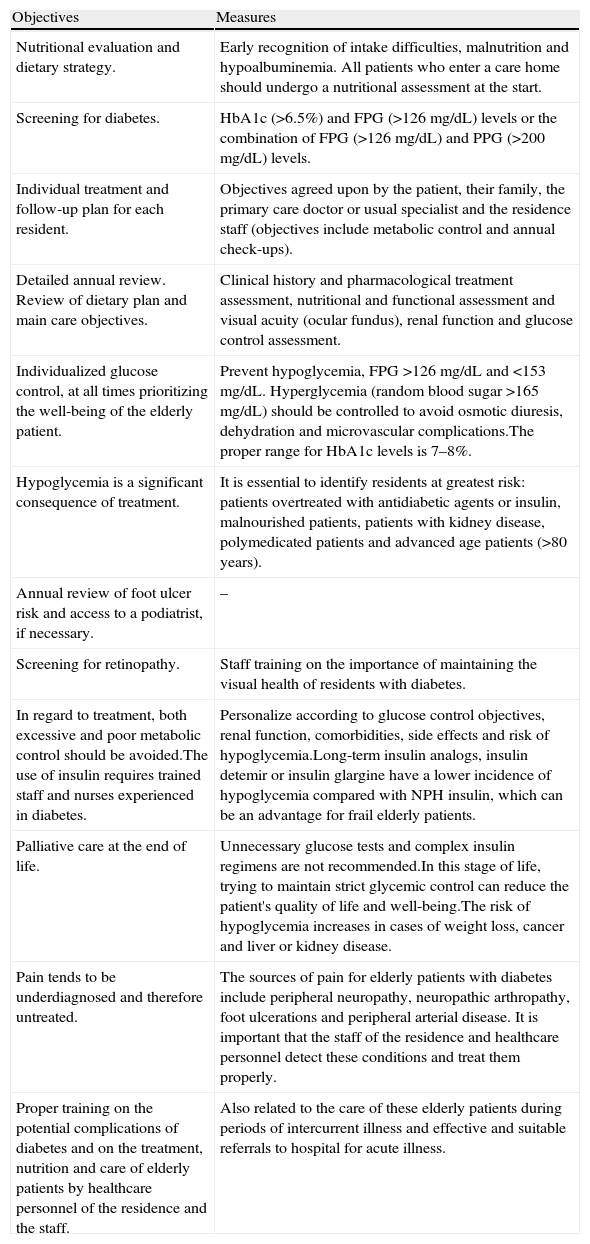

A 93-year-old woman is admitted to a conventional hospital ward for an acute respiratory infection. The patient has type 2 diabetes mellitus of approximately 15 years evolution and has no other associated comorbidities, except for progressive dependence due to senescence and a previous hospitalization for pneumonia 6 months ago. She is currently in an assisted-living residence. A recent laboratory test revealed an HbA1c level of 7.8%, with a serum creatinine level of 1.3mg/dl (MDRD, 45ml/min). Her standard treatment consists of 5mg of glibenclamide a day and 850mg of metformin every 12h. What regimen should we follow once she is hospitalized? Does she require any change in her treatment at discharge?

Una mujer de 93 años de edad ingresa en una planta de hospitalización convencional por una infección respiratoria aguda. La paciente tiene diabetes mellitus tipo 2 de unos 15 años de evolución y no presenta otras comorbilidades asociadas, salvo progresiva dependencia por senescencia y un ingreso hospitalario previo por neumonía hace 6 meses; actualmente vive en una residencia asistida. En un análisis reciente tenía una HbA1c de 7,8%, con una creatinina sérica de 1,3mg/dl (MDRD: 45ml/min). Su tratamiento habitual consistía en glibenclamida 5mg al día y metformina 850mg cada 12h. ¿Qué pauta debemos seguir una vez hospitalizada? ¿Precisa de alguna modificación de su tratamiento al alta?

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<