To assess the safety and efficacy of a basal-plus (BP) regimen with insulin glargine (as basal insulin) and insulin glulisine (as prandial insulin) with the main meal for elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) and high cardiovascular risk, following standard clinical practice.

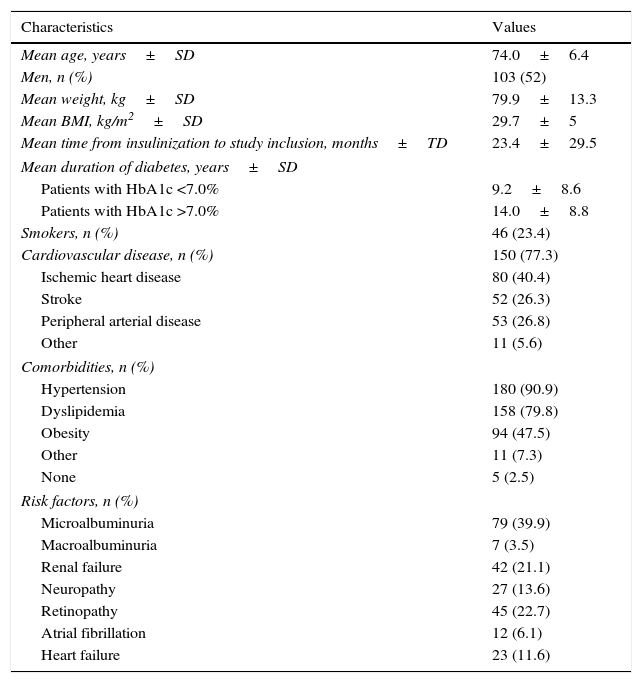

Patients and methodsAn observational, retrospective study was conducted in 21 centers of internal medicine in Spain. The study included patients aged 65 years or older with DM2, undergoing treatment with a BP regimen for 4 to 12 months before inclusion in the study and a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease or high cardiovascular risk. The primary endpoint was the change in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) from the introduction of the glulisine to inclusion in the study.

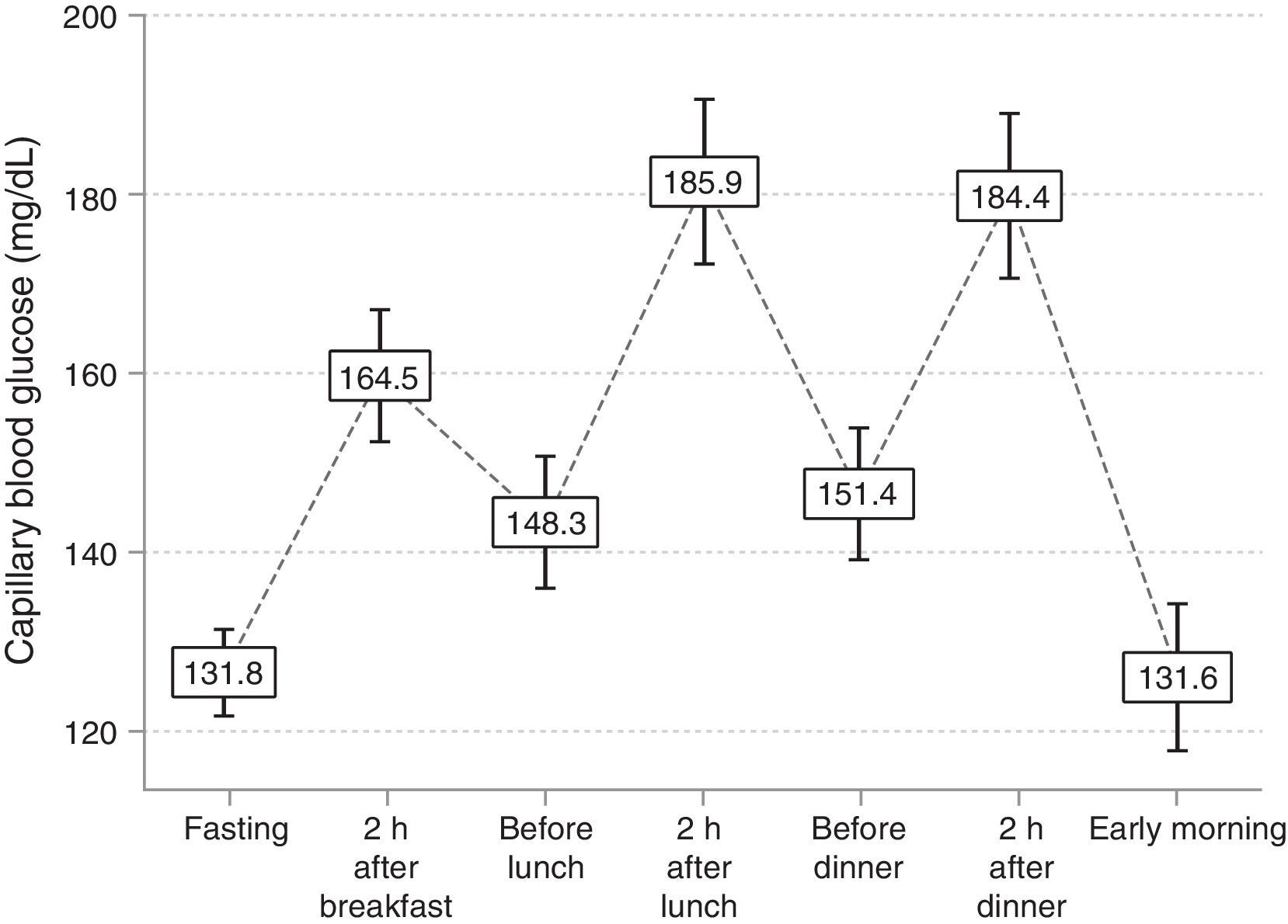

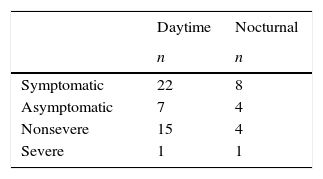

ResultsThe study included 198 patients (mean age, 74±6.4 years; males, 52%). After at least 4 months of treatment with the BP regimen, started with the addition of glulisine, the mean HbA1c value decreased significantly (9±1.5% vs. 7.7±1.1%; P<.001), and almost 24% of the patients reached HbA1c levels of 7.5–8%. Furthermore, blood glucose levels under fasting conditions decreased significantly (190.6±73.2mg/dl vs. 138.9±38.2mg/dl; P<.001). A total of 35 patients (17.7%) had some hypoglycaemia during the month prior to the start of the study, and 2 cases (1.01%) of severe hypoglycaemia were detected.

ConclusionsThe BP strategy could significantly improve blood glucose control in patients 65 years of age or older with DM2 and high cardiovascular risk and is associated with a low risk of severe hypoglycaemia.

Evaluar la eficacia y seguridad de una pauta basal plus (BP) con insulina glargina como insulina basal, e insulina glulisina como insulina prandial en la comida principal, en pacientes ancianos con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2) y alto riesgo cardiovascular, siguiendo la práctica clínica habitual.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio observacional, retrospectivo, realizado en 21 centros de medicina interna en España. Se incluyeron sujetos de edad ≥65 años con DM2, en tratamiento con pauta BP durante 4 a 12 meses antes de la inclusión en el estudio, y diagnóstico de enfermedad cardiovascular o elevado riesgo cardiovascular. La variable principal fue el cambio en la hemoglobina glucosilada (HbA1c) desde la introducción de la glulisina hasta la inclusión en el estudio.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 198 pacientes (edad media de 74±6,4 años; hombres: 52%). Tras al menos 4 meses de tratamiento con la pauta BP, iniciada con la adición de glulisina, el valor medio de HbA1c descendió significativamente (9±1,5% vs. 7,7±1,1%; p<0,001) y casi el 24% de los sujetos alcanzaron niveles de HbA1c del 7,5-8%. Asimismo, la glucemia en ayunas descendió significativamente (190,6±73,2mg/dl frente a 138,9±38,2mg/dl; p<0,001). Un total de 35 pacientes (17,7%) presentaron alguna hipoglucemia durante el mes previo al inicio del estudio, y se detectaron 2 casos (1,01%) de hipoglucemia grave.

ConclusionesLa estrategia BP podría mejorar significativamente el control glucémico en pacientes ≥65 años con DM2 y alto riesgo cardiovascular, y se asocia a un bajo riesgo de hipoglucemia grave.

Article

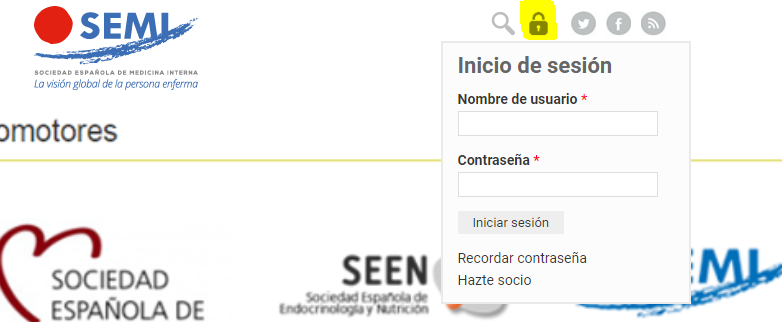

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<