To assess the cardiovascular risk according to the UKPDS risk engine; Framingham function and score comparing clinical characteristics of diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2) patients according to their habits status.

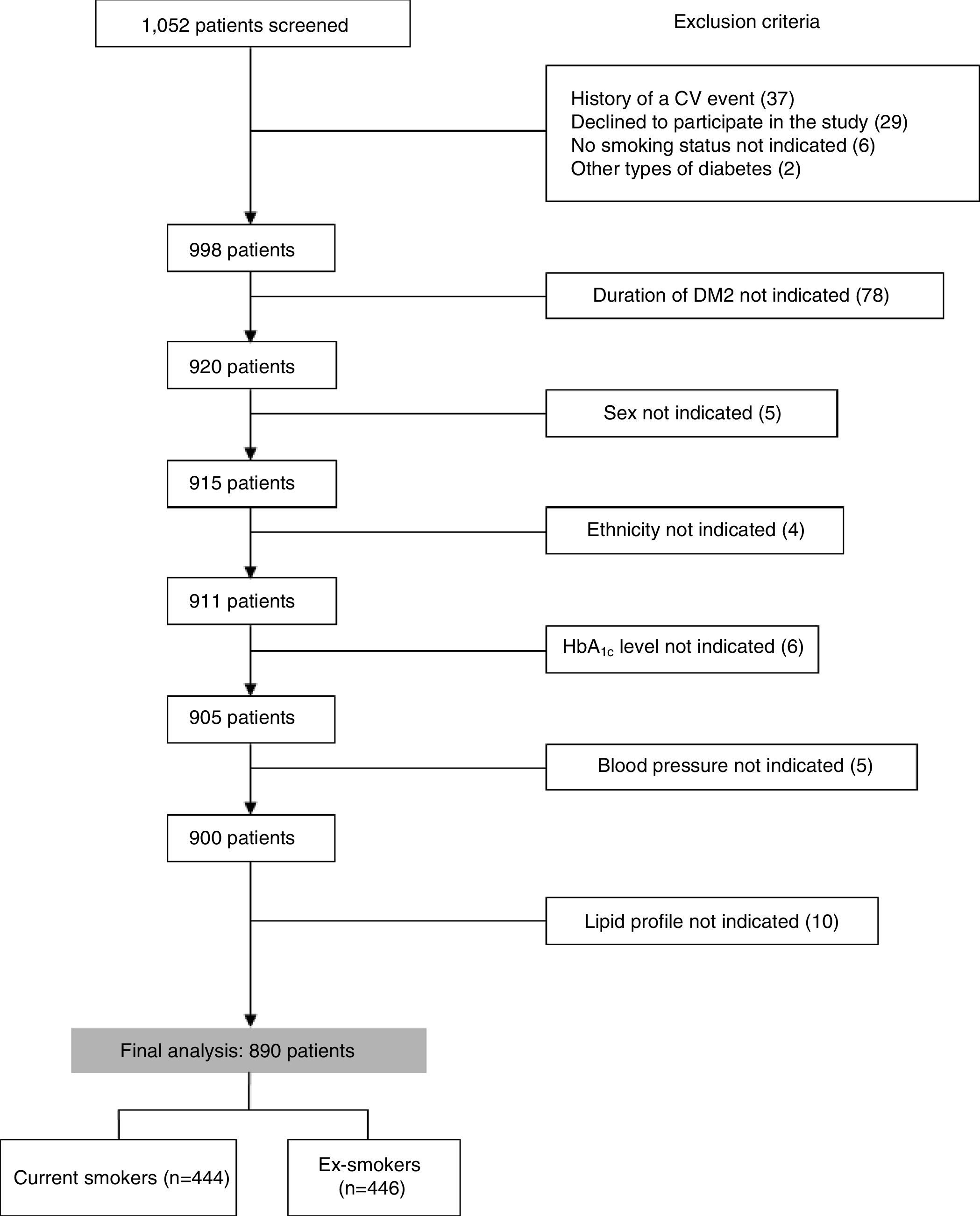

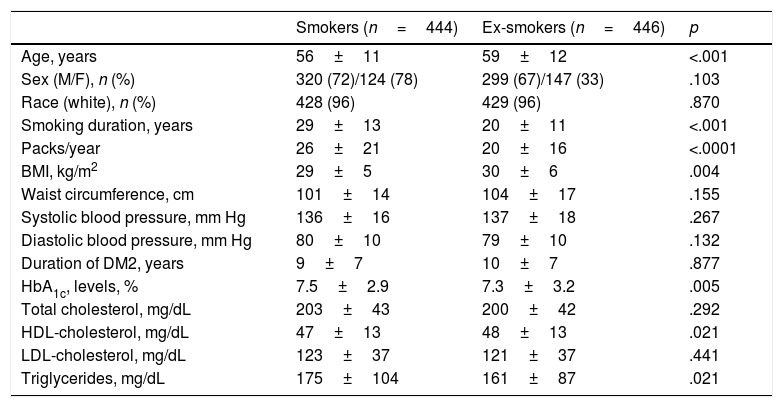

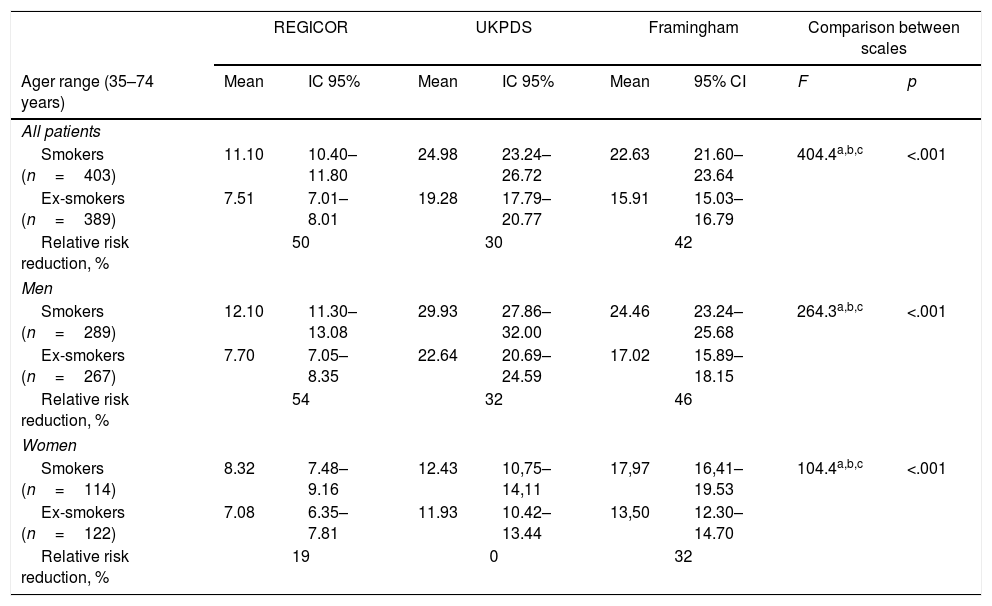

Patients and methodsA descriptive analysis was performed. A total of 890 Spanish patients with DM2 (444 smokers and 446 former-smokers) were included in a cross-sectional, observational, epidemiological multicenter nationwide study. Coronary heart disease risk at 10 years was calculated using the UKPDS risk score in both patient subgroups. Results were also compared with the Spanish calibrated (REGICOR) and updated Framingham risk scores.

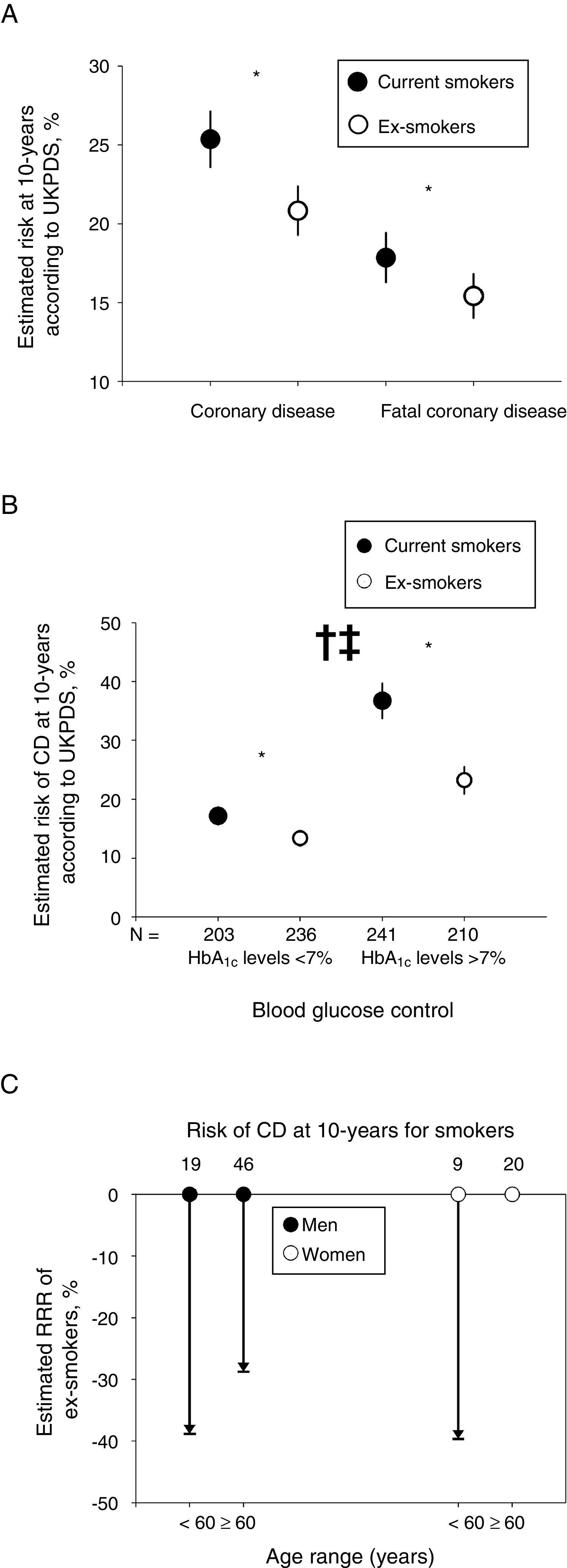

ResultsThe estimated likelihood of coronary heart disease risk at 10 years according to the UKPDS score was significantly greater in smokers compared with former-smokers. This increased risk was greater in subjects with poorer blood glucose control, and was attenuated in women ≥60 years-old. The Framingham and UKPDS scores conferred a greater estimated risk than the REGICOR equation in Spanish diabetics.

ConclusionsQuitting smoke in patients with DM2 is accompanied by a significant decrease in the estimated risk of coronary events as assessed by UKPDS. Our findings support the importance of quitting smoking among diabetic patients in order to reduce cardiovascular risk.

Evaluar el riesgo cardiovascular con la herramienta UKPDS risk engine, la función y escala Framingham y comparar las características clínicas de pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2) en base a sus hábitos.

Pacientes y métodosSe llevó a cabo un análisis descriptivo. Se incluyó a un total de 890 pacientes con DM2 (444 fumadores y 446 no fumadores) en un estudio transversal, observacional, epidemiológico, multicéntrico y a nivel nacional. Se calculó el riesgo de enfermedad coronaria a 10 años utilizando, para ello, la puntuación UKPDS en ambas cohortes. Los resultados se compararon también con las puntuaciones calibradas para España (REGICOR) y la escala de riesgo de Framingham.

ResultadosLa probabilidad estimada de enfermedad coronaria a los 10 años según la herramienta UKPDS fue ostensiblemente superior en los fumadores que en los no fumadores. Este aumento del riesgo fue mayor en sujetos con un peor control de la glucosa en sangre, y disminuye en mujeres de 60 o más años de edad. Tanto Framingham como UKPDS confieren un riesgo estimado mayor que REGICOR a los diabéticos españoles.

ConclusionesDejar de fumar en pacientes con DM2 implica un descenso significativo del riesgo estimado de eventos coronarios según la herramienta UKPDS. Nuestros descubrimientos avalan lo importante que es dejar de fumar en pacientes diabéticos a la hora de reducir el riesgo cardiovascular.

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<