Article

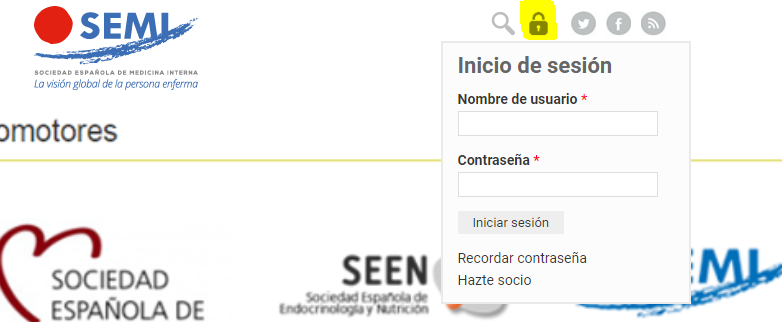

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<