Heart failure (HF) and diabetes are 2 strongly associated diseases. The main objective of this work was to analyze changes in the prognosis of patients with diabetes who were admitted for heart failure in 2 time periods.

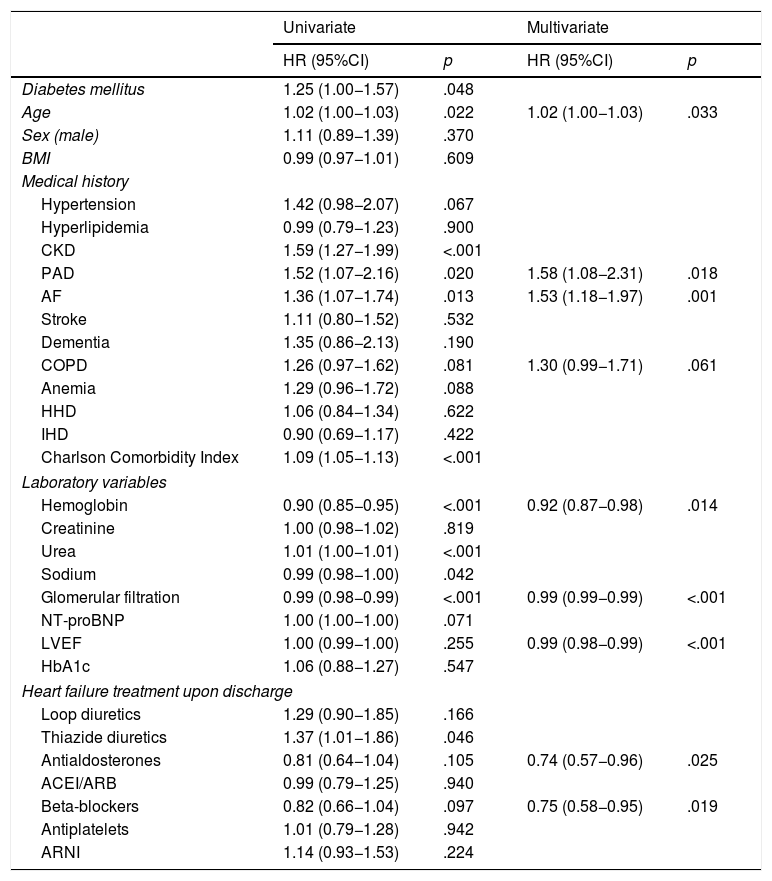

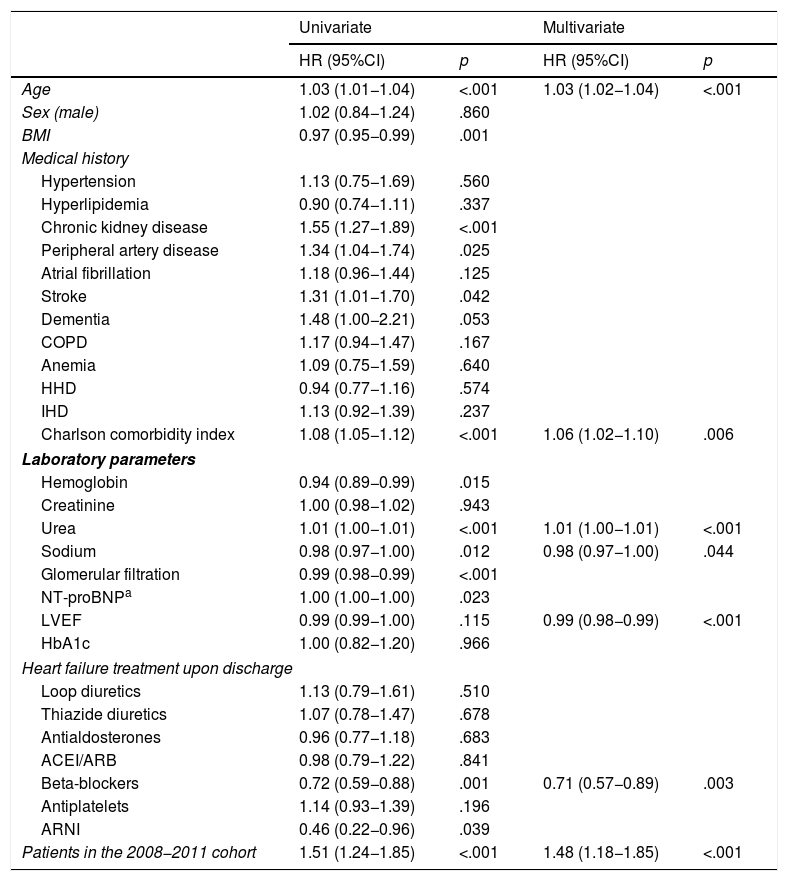

MethodsThis work is a prospective study comparing prognosis at one year of follow-up among patients with diabetes who were hospitalized for HF in either 2008–2011 or 2018. The patients are from the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine's National Heart Failure Registry (RICA, for its initials in Spanish). The primary endpoint was to analyze the composite outcome of total mortality and/or readmission due to HF in 12 months. A multivariate Cox regression model was used to evaluate the strength of association (hazard ratio [HR]) between diabetes and the outcomes between both periods.

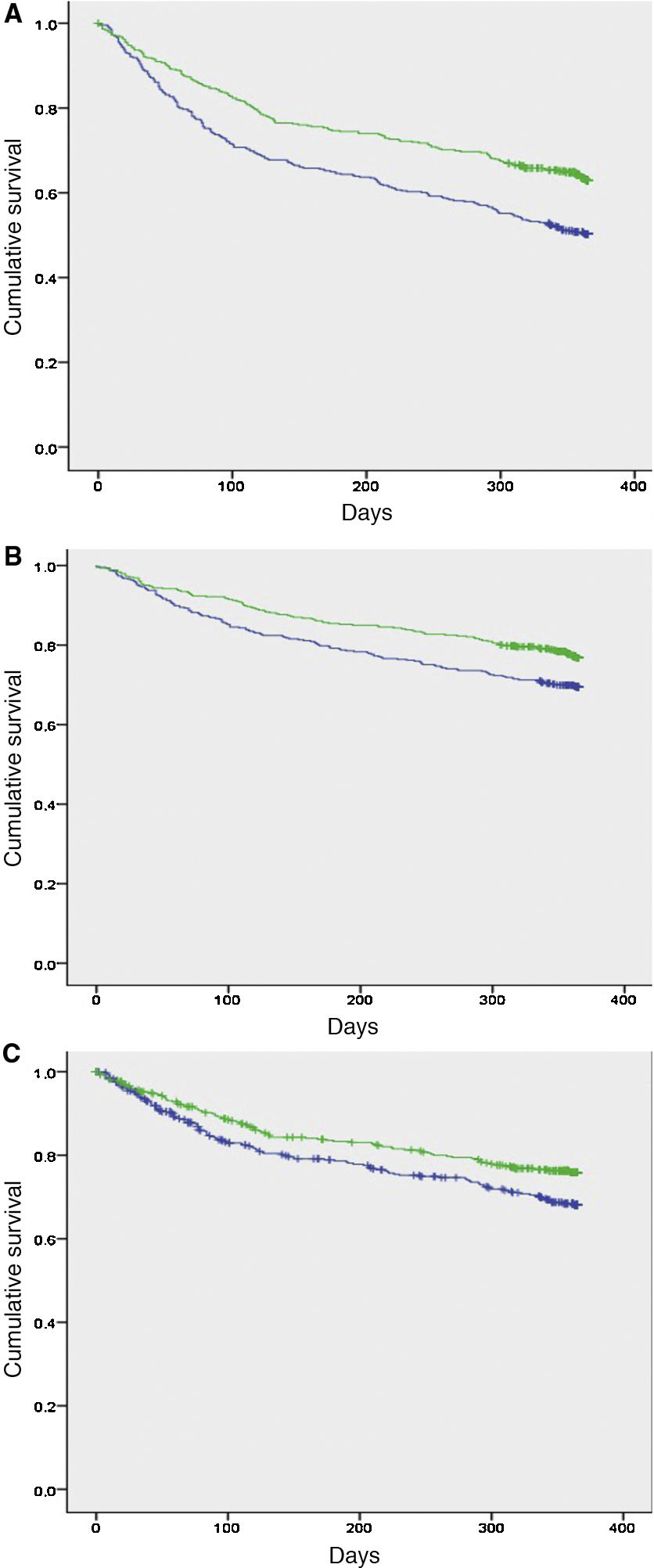

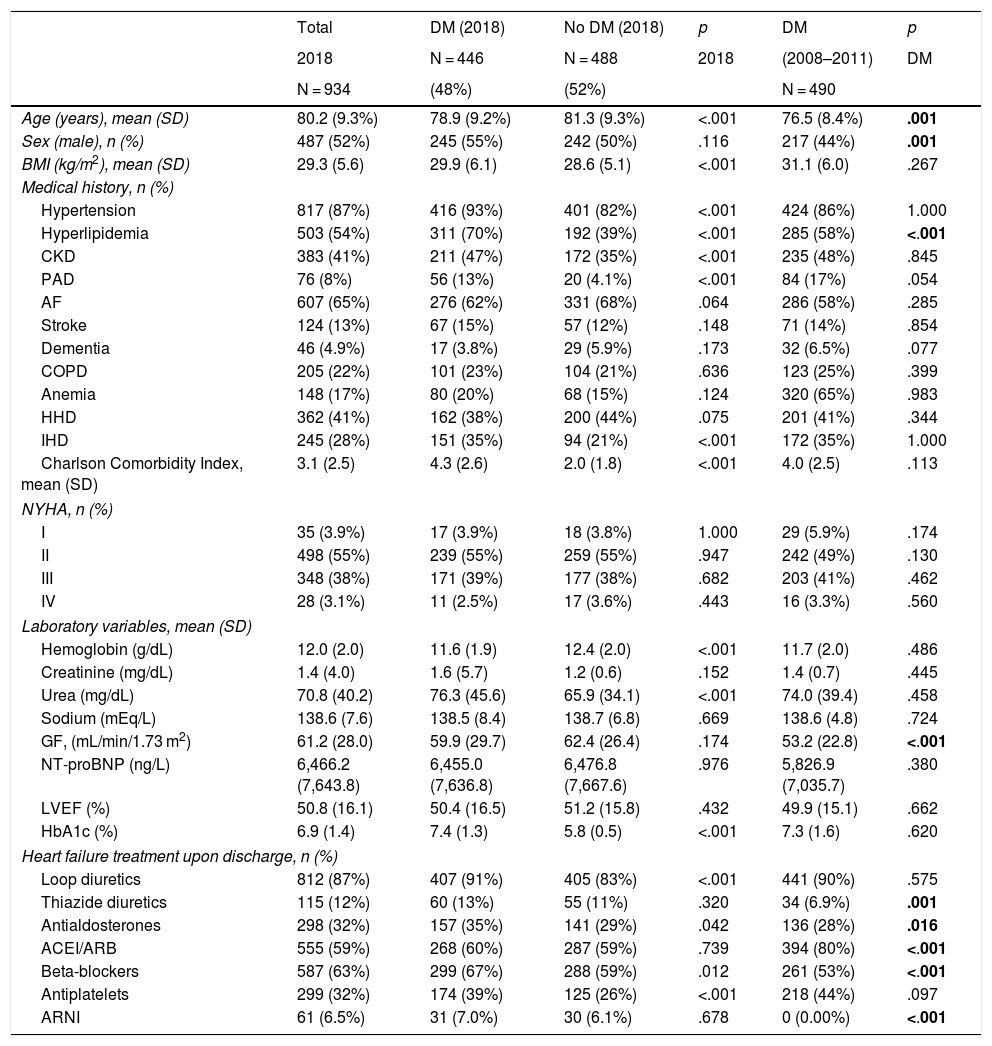

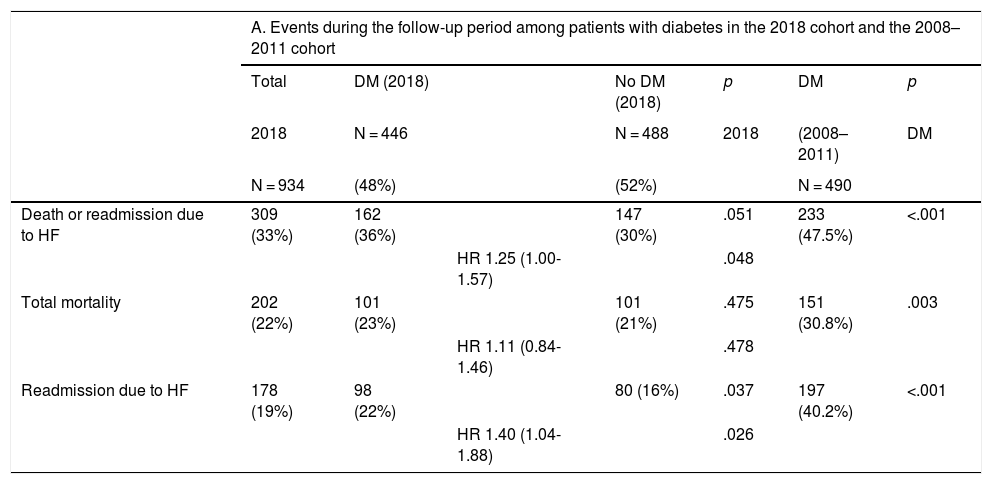

ResultsA total of 936 patients were included in the 2018 cohort, of which 446 (48%) had diabetes. The baseline characteristics of the populations from the 2 periods were similar. In patients with diabetes, the composite outcome was observed in 233 (47.5%) in the 2008–2011 cohort and 162 (36%) in the 2018 cohort [HR 1.48; 95% confidence interval (95%CI) 1.18–1.85; p < .001]. The proportion of readmissions (HR 1.39; 95%CI 1.07–1.80; p = .015) and total mortality (HR 1.60; 95%CI 1.20–2.14; p < .001) were also significantly higher in patients with diabetes from the 2008-2011 cohort compared to the 2018 cohort.

ConclusionsIn 2018, an improvement was observed in the prognosis for all-cause mortality and readmissions over one year of follow-up in patients with diabetes hospitalized for HF compared to the 2008–2011 period.

La insuficiencia cardíaca (IC) y la diabetes son 2 procesos fuertemente asociados. El objetivo principal fue analizar la evolución del pronóstico de los pacientes con diabetes que ingresan por IC a lo largo de 2 períodos.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo para comparar el pronóstico a un año de seguimiento entre los pacientes con diabetes que ingresan por IC en 2008–2011 y 2018. Los pacientes proceden del Registro Nacional de Insuficiencia Cardíaca (RICA) de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna. El objetivo primario fue analizar el desenlace combinado de mortalidad total o ingreso por IC durante 12 meses. Se utilizó una regresión multivariante de Cox para evaluar la fuerza de asociación (hazard ratio [HR]) de la diabetes y los desenlaces entre ambos períodos.

ResultadosSe incluyó a un total de 936 pacientes en la cohorte de 2018, de los que 446 (48%) tenían diabetes. Las características basales de la población de los 2 períodos fueron similares. En los pacientes con diabetes se observó el desenlace combinado en 233 (47,5%) en la cohorte de 2008−2011 y 162 (36%) en la cohorte de 2018 (HR 1,48; intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%] 1,18–1,85; p < 0,001). La proporción de ingresos (HR 1,39; IC95% 1,07–1,80; p = 0,015) y la mortalidad total (HR 1,60; IC95% 1,20–2,14; p < 0,001) también fueron significativamente mayores en los pacientes con diabetes de la cohorte de 2008–2011 con respecto a la del 2018.

ConclusionesEn 2018 se observa una mejoría del pronóstico de la mortalidad total y los reingresos durante un año de seguimiento en pacientes con diabetes hospitalizados por IC con respecto al período de 2008–2011.

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<