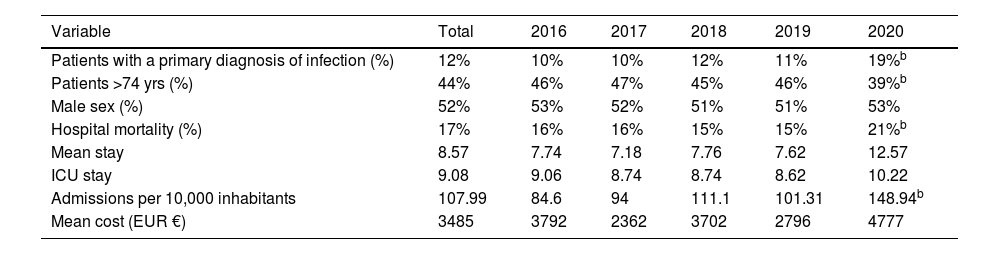

This work aimed to review patients discharged from Spanish hospitals with a principal diagnosis of infection during a 5-year period, including the first year of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Materials and methodThis work analyzed the Basic Minimum Data Set (CMBD) of patients discharged during the 2016⬜2020 period from hospitals in the Spanish National Health Service in order to identify cases with a principal diagnosis of an infectious disease according to the ICD-10-S code. All patients older than 14 years of age admitted to a conventional ward or intensive care unit, excluding labor and delivery, were included in the analysis and were evaluated based on the discharging department.

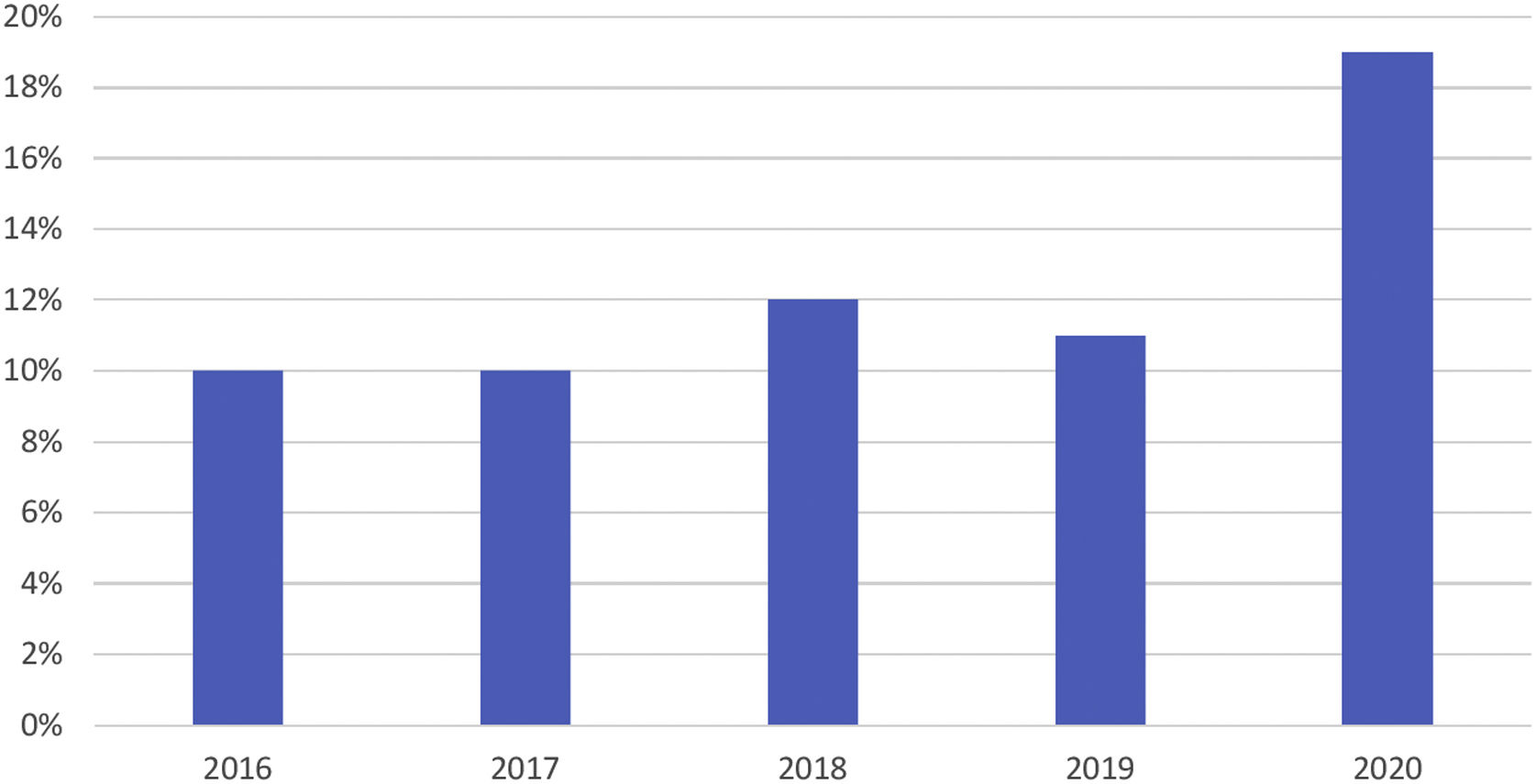

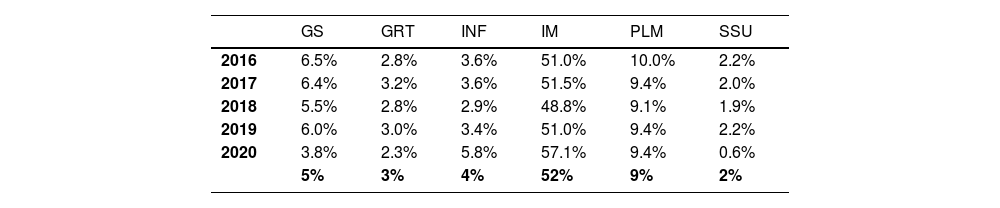

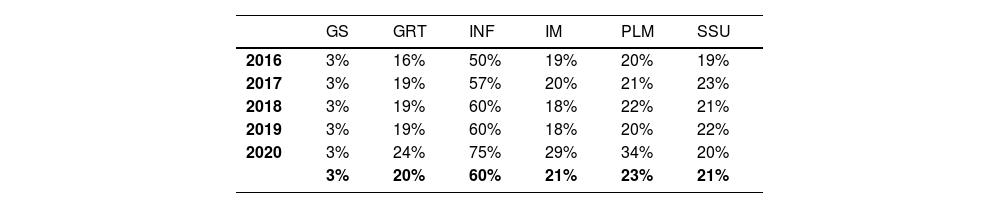

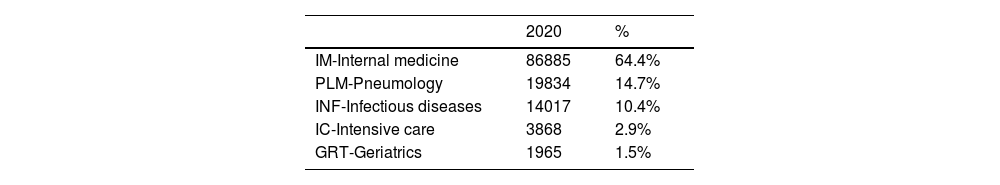

ResultsPatients discharged with infectious diseases as the principal diagnosis have increased from 10% to 19% in recent years. A large part of the growth is due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Internal medicine departments cared for more than 50% of these patients, followed by pulmonology (9%) and surgery (5%). In 2020, 57% of patients with a principal diagnosis of infection were discharged by internists, who cared for 67% of patients with SARS CoV-2.

ConclusionsAt present, more than half of patients admitted with a principal diagnosis of infection are discharged from internal medicine departments. Given the growing complexity of infections, the authors advocate for an approach in which training allows for specialization, but within a generalist context, for the better management of these patients.

Revisar los pacientes atendidos en los hospitales españoles dados de alta con un diagnóstico principal de infección en un periodo de 5 años, incluyendo el primer año de la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2.

Material y métodosSe han analizado los datos del Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos (CMBD) de los pacientes dados de alta durante el periodo 2016⬜2020 de los hospitales del Sistema Nacional de Salud de España identificando aquellos que tuvieran un diagnóstico principal de enfermedad infecciosa según el código CIE-10-S. Se han incluido en el análisis todos los pacientes mayores de 14 años que hubieran ingresado en una planta convencional o de cuidados intensivos, excluyendo los partos, y se han evaluado las altas en función del servicio de alta.

ResultadosLos pacientes dados de alta con patología infecciosa han aumentado del 10% al 19% en los últimos años, y gran parte del crecimiento se debe a la epidemia por SARS-CoV-2. Los servicios de medicina interna atienden a más del 50% de estos pacientes, seguidos de neumología (9%) y cirugía general (5%). En el año 2020 el 57% de los pacientes con diagnóstico principal de infección fueron dados de alta por internistas, que atendieron al 67% de los pacientes con SARS-CoV-2.

ConclusionesActualmente más de la mitad de los pacientes que ingresan con diagnóstico principal de infección son dados de alta en medicina interna. Dada la complejidad creciente de las infecciones, abogamos por un abordaje en el que un área de capacitación permita una especialización, pero dentro de un contexto generalista, para el mejor manejo de estos pacientes.

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<