Heart failure (HF) is a syndrome of epidemic proportions and one of the main reasons for hospital admission. Patient registries provide real-world clinical practice information which is complementary to clinical trials. RICA-2 is a registry of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine. Its main goal is to know the clinical and epidemiological characteristics and prognostic factors of patients with HF treated in Internal Medicine Departments. The objective of this study is to present the design of the RICA-2, the baseline characteristics of the first 1000 patients included and their comparison with those of the historical cohort of the RICA registry.

MethodsObservational, multicentre and prospective study of patients with HF with the following inclusion criteria: age equal to or greater than 18 years old, diagnosis of HF according to the European Guidelines, indistinct inclusion in decompensation or stable phase, of patients with de novo HF or chronic HF, regardless of left ventricular ejection fraction, aetiology and comorbidities.

ResultsRICA-2 patients have advanced age (83 years old) and 51% are women. The comorbidity burden is higher than in the RICA registry (5 points in the Charlson comorbidity index), with predominating chronic decompensated HF (74%), hypertensive aetiology (39%) and preserved ejection fraction (52%). Most patients are pre-frail or vulnerable and are at risk of malnutrition.

ConclusionThe RICA-2 represents a contemporary cohort of patients that will provide us with clinical, epidemiological and prognostic information on patients with acute and chronic HF treated in Internal Medicine.

La insuficiencia cardíaca (IC) es un síndrome de proporciones epidémicas y uno de los principales motivos de ingreso hospitalario. Los registros de pacientes proporcionan información sobre la práctica clínica real complementaria a los ensayos clínicos. El RICA-2 es un registro de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna (MI) cuyo objetivo principal es conocer las características clínicas, epidemiológicas y factores pronósticos de los pacientes con IC atendidos en MI. El objetivo es presentar el diseño del RICA-2, las características basales de los primeros 1000 pacientes incluidos y su comparación con los de la cohorte histórica del registro RICA.

MétodosEstudio observacional, multicéntrico y prospectivo de pacientes con IC con los siguientes criterios de inclusión: edad igual o superior a 18 años, diagnóstico de IC según las Guías Europeas, inclusión indistinta en fase de descompensación o estable, de pacientes con IC «de debut» o con IC crónica, independientemente de la fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo (FEVI), la etiología y las comorbilidades.

ResultadosLos pacientes del RICA-2 son de edad avanzada (83 años) y el 51% son mujeres. La comorbilidad es mayor que en el RICA (índice de Charlson de 5), predominando la IC crónica descompensada (74%), de etiología hipertensiva (39%) y FEVI preservada (52%). La mayoría de pacientes son pre-frágiles o vulnerables y están en riesgo de desnutrición.

ConclusiónEl registro RICA-2 representa una cohorte de pacientes contemporánea que nos aportará información clínica, epidemiológica y pronóstica de los pacientes con IC aguda y crónica atendidos en MI.

Heart failure (HF) is a heterogeneous syndrome affecting over 64 million people around the world that involves a decline in functional capacity and quality of life and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality and elevated resource use and health costs. Heart failure is the main cause of hospitalisation in patients over the age of 65 and represents between 1% and 2% of all hospitalisations in the western world. For that reason, HF has become a significant global public health priority.1 In recent decades, HF prognoses, particularly with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), have improved greatly thanks to the appearance of new treatments tested in large and robust clinical trials.2 These clinical trials are excellent tools for comparing the efficacy and safety of various interventions, but their strict inclusion and exclusion criteria mean that some patient subgroups are not represented, preventing results from being generalised to the entire patient population.3 Therefore, faced with a need to discover what is happening in clinical practice or in “real life”, patient registries emerged, which provide information to supplement clinical trials.3,4

In 2008, the Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation Workgroup from the Spanish Society for Internal Medicine (SEMI) launched the RICA registry with the aim of determining the clinical and prognostic characteristics of HF patients treated in Internal Medicine (IM) departments.5,6 After 13 years of recruitment, the RICA registry included over 7,000 patients, and the data was used to publish over 50 journal articles in national and international indexed scientific journals, addressing multiple clinical, epidemiological, therapeutic, and prognostic, as well as social and organisational, aspects that affect this syndrome.7–22

The notable changes HF has undergone over the past decade in terms of both clinical and epidemiological aspects, as well as diagnostic criteria and therapeutic targets, has given rise to the need to update the initial research questions and modify the variables needed to answer them. For those reasons, the RICA registry Research Committee decided to update the registry by creating a new registry called RICA-223 (Fig. 1).

The aim of this paper is to present the design of the new RICA-2 registry as well as the baseline characteristics of the first 1000 patients included in the registry and to compare them with those of the historic cohort from the original RICA registry.

MethodsStudy design and populationRICA-2 is an observational, multi-sectional, prospective study. Patients are recruited in IM departments from hospitals across Spain and Portugal whose researchers are members of the SEMI Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation Workgroup and the HF Group from the Portuguese Society of Internal Medicine, respectively.

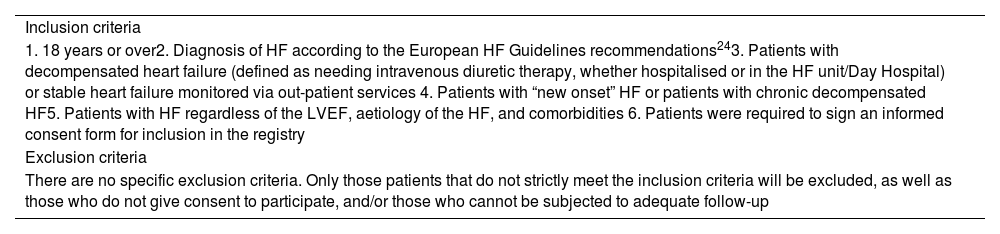

Patient selection criteriaPatient inclusion in RICA-2 was performed prospectively, either during the decompensation phase or the stable phase through out-patient consultations (unlike the RICA registry, which only included patients via hospital admission due to decompensation and unstable patients via outpatient consultations). Each participating site was assigned a minimum number of patients to include each year adapted to the size of the hospital. Only those patients who strictly meet the European Society of Cardiology’s HF diagnostic criteria are included.24 The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in greater detail in Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

| 1. 18 years or over2. Diagnosis of HF according to the European HF Guidelines recommendations243. Patients with decompensated heart failure (defined as needing intravenous diuretic therapy, whether hospitalised or in the HF unit/Day Hospital) or stable heart failure monitored via out-patient services 4. Patients with “new onset” HF or patients with chronic decompensated HF5. Patients with HF regardless of the LVEF, aetiology of the HF, and comorbidities 6. Patients were required to sign an informed consent form for inclusion in the registry |

| Exclusion criteria |

| There are no specific exclusion criteria. Only those patients that do not strictly meet the inclusion criteria will be excluded, as well as those who do not give consent to participate, and/or those who cannot be subjected to adequate follow-up |

Abbreviations: HF: heart failure; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction.

The primary objective of the RICA-2 registry is to determine the clinical and epidemiological characteristics and prognostic factors of HF patients treated in IM departments in Spain and Portugal. The secondary or specific aims of the RICA-2 registry are the following: 1). Determine the clinical and epidemiological aspects, phenotypic and prognostic characteristics of patients with HF and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (HFpEF); 2). Analyse how functional status, cognition, and frailty impact the prognosis of HF patients; 3). Analyse the nutritional status of HF patients and discover how malnutrition impacts their prognosis; and 4). Determine the best tools for evaluating congestion, as well as the best strategies for achieving decongestion in patients with HF during the acute decompensation phase.

The specific aim of this paper is to present the baseline characteristics of the first 1000 patients included in the RICA-2 registry and to compare them with the historic cohort from the RICA registry (5644 validated patients at study end).

Study visits and variablesThe study visits include a screening visit at the start, a follow-up visit after 30 days (only for patients included following a decompensation episode), and two follow-up visits at one and two years. The baseline study variables are recorded during the screening visit and the follow-up variables at the 30-day and 1- and 2-year follow-up visits after inclusion. Those variables are listed in greater detail in Table 2.

RICA-2 study variables.

| Screening visit | |

|---|---|

| Demographic variables | Age and sex |

| Body composition | Body mass index |

| Variables related to HF | HF aetiologyNYHA functional classPrior admissions and emergency department visits due to HF |

| Comorbidities6 | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| Social variables | Place of residence and care needs |

| Functional status25 | Barthel Index |

| Cognitive status13 | Delirium and Pfeiffer’s test |

| Frailty26 | FRAIL scalesa and Clinical Frailty Scoreb |

| Advanced HF and palliative care needs27 | EPICTER scorec |

| Nutritional status28,29 | NRSd and MNA scorese |

| Variables of acute decompensation24 | EVEREST scorefPrecipitating factorsPharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment |

| Analytical parameters24,30 | Hemogram and biochemical profile parametersgNatriuretic peptides and troponin Carbohydrate antigen 125 Iron kinetics parametersUrinalysisg |

| Complementary tests | ElectrocardiogramEchocardiogram Chest X-ray Pulmonary and vena cava ultrasoundOther proceduresh |

| Amyloidosis diagnostic criteria31 | European Society of Cardiology criteria |

| Background therapy | Therapy related and unrelated to HF |

| Follow-up visits | |

| Results | Vital status and cause of death (in case of exitus)Hospitalisations and hospitalisations due to HF Emergency department visits due to HF |

| Analytical parameters | Hemogram, renal function, electrolytes and natriuretic peptides |

| Treatment | Optimization of HF treatment |

Abbreviations: HF: heart failure; MNA: Mini Nutritional Assessment; NRS: Nutritional Risk Screening; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

FRAIL score: assesses five criteria (fatigue, resistance, deambulation, illness, and loss of weight). Scale interpretation: non-frail (0 points), pre-frail (1 or 2 points), and frail (3–5 points).

Clinical Frailty Score: graphically describes the different degrees of frailty and disability according to their level of vulnerability. It varies from robust and in full health (stage 1) to terminally ill (stage 9). The first three stages are considered non-frail, the fourth is considered vulnerable, and the fifth to the eighth are considered disabled-dependent.

EPICTER score: assesses and scores the following variables: age, NYHA functional class, history of COPD, chronic kidney disease and dementia, estimated survival < 6 months, and acceptance of a palliative approach by the patient. It predicts the risk of mortality at 6 months: LOW: 0–3 points (5.7%), MEDIUM: 4–9 points (17.8%), HIGH: 10–16 points (35.1%), and VERY HIGH: 17–25 points (53.8%).

NRS: nutritional status screening tool based on BMI, weight loss, reduced dietary intake, and severity of the disease. It defines the risk of malnutrition as: no risk (0 points), low risk (1–2 points), medium risk (3–4 points), and high risk (5 points).

MNA: screening tool that helps identify malnourished elderly patients or those at risk of malnutrition based on BMI, weight loss, reduced dietary intake, mobility, psychological stress, or acute disease and neuropsychological problems. A score > 12 indicates normal nutritional status; between 8 and 11 indicates a risk of malnutrition; < 7 indicates malnutrition.

EVEREST: congestion assessment that includes 6 clinical parameters (dyspnoea, orthopnoea, jugular vein distension, rales, oedema, and fatigue) scored from 0 to 3 (total scale score from 0 to 18).

Including blood glucose, renal function (urea, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration via CKD-EPI), uric acid, electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, magnesium), blood gas parameters, C-reactive protein, liver enzymes, lipids (cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides), and albumin. The urinalysis includes sodium, potassium, chloride, and albumin-creatinine ratio).

Since the RICA-2 registry is “open” and has different objectives, the sample size has not been calculated, but based on the experience from implementation of the RICA registry, we estimate around 1000 patients will be included per year, with the goal of including at least 5000 patients over a 5-year period. To achieve this inclusion rate, the same strategy was followed that has been used in other observational studies from our workgroup,27,32 which consists of assigning each site a minimum number of patients to include each year, with this number being proportional to the number of beds at the site. For this study, a descriptive analysis is carried out in which the categorical variables are expressed in numbers and percentages and the quantitative variables in medians and interquartile ranges. No statistical comparison tests are included nor are p-values reported between the two cohorts. The main reason for this decision is that, in studies with large sample sizes, p-values in isolation can be statistically significant even when the observed differences may have no clinical relevance. The fact that this study does not include analyses with measures of association (such as risks or odds with their respective confidence intervals), which do provide information about statistical significance and clinical relevance, justifies this manner of presenting the data.

Ethical aspectsThe patients enrolled in this study are treated according to regular medical care since this is an observational study that does not modify regular clinical practice. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Hospital Universitari Dr. Josep Trueta de Girona Ethics Committee. All the participating subjects are required to sign and informed consent.

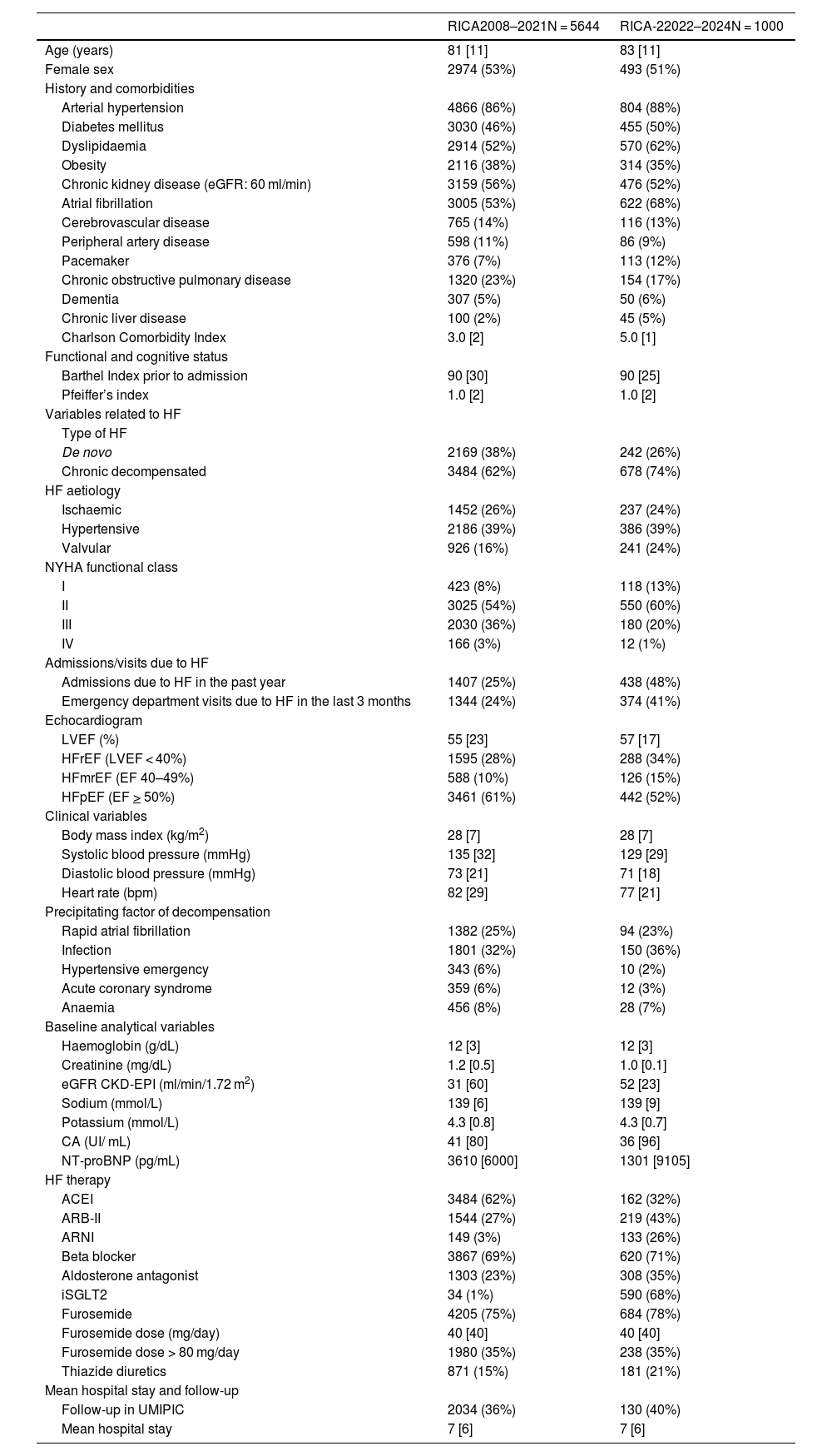

ResultsRecruitment for the RICA-2 registry started on 1 December 2022 and by February 2024 had reached enrolment of the first 1000 patients, 47% via external consultation (during the stable phase) and 53% during the decompensation phase. The baseline characteristics of the patients in the RICA-2 registry and from the RICA historic cohort are presented in greater detail in Table 3. The patients included in both registries are older patients (median 81-83 years) and 51-53% are female. Patients from both registries have a higher comorbidity burden, with an increase in the median Charlson Index score from 3 to 5 points between RICA and RICA-2, impacting an increase in the cardiovascular risk factors, atrial fibrillation, and chronic liver disease. In relation to HF itself, compared to the RICA historic cohort, the RICA-2 registry has more chronic patients than de novo patients, more patients in functional class II and fewer in functional class III according to the NYHA, more admissions and ED visits due to HF, and more patients with HF and reduced LVEF (HFrEF). On the contrary, there are no differences between the two registries for the most common aetiology of HF nor in the precipitating factor of decompensation. With regards to the baseline analytical variables, we have observed that RICA-2 patients have better kidney function values and lower NT-proBNP levels. In terms of HF treatment, an increase has been observed in patients treated with angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), aldosterone antagonists, and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. Lastly, we have not observed differences regarding mean hospital stay nor the percentage of patients undergoing follow-up in the HF Patient Comprehensive Care Unit (UMIPIC as per the Spanish acronym).

Baseline descriptive characteristics of the patients included in the RICA and RICA-2 registries.

| RICA2008–2021N = 5644 | RICA-22022–2024N = 1000 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 81 [11] | 83 [11] |

| Female sex | 2974 (53%) | 493 (51%) |

| History and comorbidities | ||

| Arterial hypertension | 4866 (86%) | 804 (88%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3030 (46%) | 455 (50%) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 2914 (52%) | 570 (62%) |

| Obesity | 2116 (38%) | 314 (35%) |

| Chronic kidney disease (eGFR: 60 ml/min) | 3159 (56%) | 476 (52%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3005 (53%) | 622 (68%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 765 (14%) | 116 (13%) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 598 (11%) | 86 (9%) |

| Pacemaker | 376 (7%) | 113 (12%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1320 (23%) | 154 (17%) |

| Dementia | 307 (5%) | 50 (6%) |

| Chronic liver disease | 100 (2%) | 45 (5%) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 3.0 [2] | 5.0 [1] |

| Functional and cognitive status | ||

| Barthel Index prior to admission | 90 [30] | 90 [25] |

| Pfeiffer’s index | 1.0 [2] | 1.0 [2] |

| Variables related to HF | ||

| Type of HF | ||

| De novo | 2169 (38%) | 242 (26%) |

| Chronic decompensated | 3484 (62%) | 678 (74%) |

| HF aetiology | ||

| Ischaemic | 1452 (26%) | 237 (24%) |

| Hypertensive | 2186 (39%) | 386 (39%) |

| Valvular | 926 (16%) | 241 (24%) |

| NYHA functional class | ||

| I | 423 (8%) | 118 (13%) |

| II | 3025 (54%) | 550 (60%) |

| III | 2030 (36%) | 180 (20%) |

| IV | 166 (3%) | 12 (1%) |

| Admissions/visits due to HF | ||

| Admissions due to HF in the past year | 1407 (25%) | 438 (48%) |

| Emergency department visits due to HF in the last 3 months | 1344 (24%) | 374 (41%) |

| Echocardiogram | ||

| LVEF (%) | 55 [23] | 57 [17] |

| HFrEF (LVEF < 40%) | 1595 (28%) | 288 (34%) |

| HFmrEF (EF 40–49%) | 588 (10%) | 126 (15%) |

| HFpEF (EF > 50%) | 3461 (61%) | 442 (52%) |

| Clinical variables | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28 [7] | 28 [7] |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 135 [32] | 129 [29] |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73 [21] | 71 [18] |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 82 [29] | 77 [21] |

| Precipitating factor of decompensation | ||

| Rapid atrial fibrillation | 1382 (25%) | 94 (23%) |

| Infection | 1801 (32%) | 150 (36%) |

| Hypertensive emergency | 343 (6%) | 10 (2%) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 359 (6%) | 12 (3%) |

| Anaemia | 456 (8%) | 28 (7%) |

| Baseline analytical variables | ||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12 [3] | 12 [3] |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2 [0.5] | 1.0 [0.1] |

| eGFR CKD-EPI (ml/min/1.72 m2) | 31 [60] | 52 [23] |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139 [6] | 139 [9] |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.3 [0.8] | 4.3 [0.7] |

| CA (UI/ mL) | 41 [80] | 36 [96] |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 3610 [6000] | 1301 [9105] |

| HF therapy | ||

| ACEI | 3484 (62%) | 162 (32%) |

| ARB-II | 1544 (27%) | 219 (43%) |

| ARNI | 149 (3%) | 133 (26%) |

| Beta blocker | 3867 (69%) | 620 (71%) |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 1303 (23%) | 308 (35%) |

| iSGLT2 | 34 (1%) | 590 (68%) |

| Furosemide | 4205 (75%) | 684 (78%) |

| Furosemide dose (mg/day) | 40 [40] | 40 [40] |

| Furosemide dose > 80 mg/day | 1980 (35%) | 238 (35%) |

| Thiazide diuretics | 871 (15%) | 181 (21%) |

| Mean hospital stay and follow-up | ||

| Follow-up in UMIPIC | 2034 (36%) | 130 (40%) |

| Mean hospital stay | 7 [6] | 7 [6] |

Abbreviations: ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB-II: angiotensin II receptor blockers; ARNI: angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; eGF: estimated glomerular filtration; HF: heart failure; HFrEF: HF with reduced LVEF; HFmrEF: HF with mid-range LVEF; HFpEF: HF with preserved LVEF; NYHA: New York Heart Association; SGLT2i: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor; UMIPIC: Unidad de Manejo Integral de Pacientes con Insuficiencia Cardiaca [Comprehensive Management Unit for Heart Failure Patients].

The quantitative variables are expressed in medians [interquartile range] and the categorical variables as numbers (percentages).

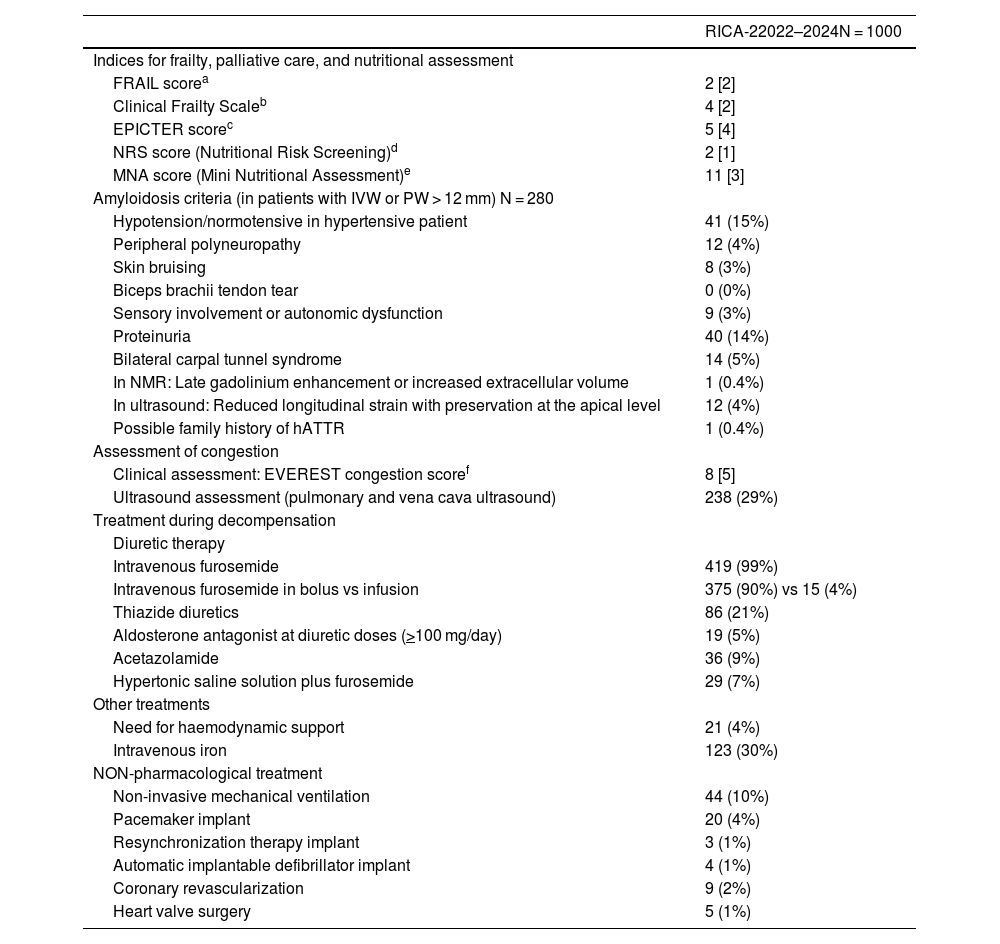

Table 4 lists the variables that are only recorded in the RICA-2 registry and were not recorded in the RICA historic cohort. In terms of frailty, the median of the scales used to assess this variable show that the majority of patients are pre-frail (2 points on the FRAIL scale) or vulnerable (stage 4 in the Clinical Frailty Scale). On the other hand, the mean score from the nutritional screening scales shows that the majority of patients are at risk of malnutrition. With respect to mortality risk, estimated by the EPICTER palliative care score, the mean score of 5 points indicates that the risk of mortality at 6 months is at least moderate. As far as amyloidosis, of the 280 patients presenting with left ventricular hypertrophy (defined as an interventricular wall or superior posterior wall thickness greater than 12 mm), 138 (49%) of them also present one or more diagnostic criteria for suspicion as defined by the European Society of Cardiology.31

RICA-2 registry variables: frailty, nutrition, amyloidosis, and congestion criteria.

| RICA-22022–2024N = 1000 | |

|---|---|

| Indices for frailty, palliative care, and nutritional assessment | |

| FRAIL scorea | 2 [2] |

| Clinical Frailty Scaleb | 4 [2] |

| EPICTER scorec | 5 [4] |

| NRS score (Nutritional Risk Screening)d | 2 [1] |

| MNA score (Mini Nutritional Assessment)e | 11 [3] |

| Amyloidosis criteria (in patients with IVW or PW > 12 mm) N = 280 | |

| Hypotension/normotensive in hypertensive patient | 41 (15%) |

| Peripheral polyneuropathy | 12 (4%) |

| Skin bruising | 8 (3%) |

| Biceps brachii tendon tear | 0 (0%) |

| Sensory involvement or autonomic dysfunction | 9 (3%) |

| Proteinuria | 40 (14%) |

| Bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome | 14 (5%) |

| In NMR: Late gadolinium enhancement or increased extracellular volume | 1 (0.4%) |

| In ultrasound: Reduced longitudinal strain with preservation at the apical level | 12 (4%) |

| Possible family history of hATTR | 1 (0.4%) |

| Assessment of congestion | |

| Clinical assessment: EVEREST congestion scoref | 8 [5] |

| Ultrasound assessment (pulmonary and vena cava ultrasound) | 238 (29%) |

| Treatment during decompensation | |

| Diuretic therapy | |

| Intravenous furosemide | 419 (99%) |

| Intravenous furosemide in bolus vs infusion | 375 (90%) vs 15 (4%) |

| Thiazide diuretics | 86 (21%) |

| Aldosterone antagonist at diuretic doses (>100 mg/day) | 19 (5%) |

| Acetazolamide | 36 (9%) |

| Hypertonic saline solution plus furosemide | 29 (7%) |

| Other treatments | |

| Need for haemodynamic support | 21 (4%) |

| Intravenous iron | 123 (30%) |

| NON-pharmacological treatment | |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 44 (10%) |

| Pacemaker implant | 20 (4%) |

| Resynchronization therapy implant | 3 (1%) |

| Automatic implantable defibrillator implant | 4 (1%) |

| Coronary revascularization | 9 (2%) |

| Heart valve surgery | 5 (1%) |

Abbreviations: IVW: interventricular wall; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance; PW: posterior wall.

The quantitative variables are expressed in medians [interquartile range] and categorical variables as numbers (percentages).

FRAIL score: assesses five criteria (fatigue, resistance, deambulation, illness, and loss of weight). Scale interpretation: non-frail (0 points), pre-frail (1 or 2 points), and frail (3–5 points).

Clinical Frailty Score: graphically describes the different degrees of frailty and disability according to their level of vulnerability. It varies from robust and in full health (stage 1) to terminally ill (stage 9). The first three stages are considered non-frail, the fourth is considered vulnerable, and the fifth to the eighth are considered disabled-dependent.

EPICTER score: assesses and scores the following variables: age, NYHA functional class, history of COPD, chronic kidney disease and dementia, estimated survival < 6 months, and acceptance of a palliative approach by the patient. It predicts the risk of mortality at 6 months: LOW: 0–3 points (5.7%), MEDIUM: 4–9 points (17.8%), HIGH: 10–16 points (35.1%), and VERY HIGH: 17–25 points (53.8%).

NRS: nutritional status screening tool based on BMI, weight loss, reduced dietary intake, and severity of the disease. It defines the risk of malnutrition as: no risk (0 points), low risk (1–2 points), medium risk (3–4 points), and high risk (5 points).

MNA: screening tool that helps identify malnourished elderly patients or those at risk of malnutrition based on BMI, weight loss, reduced dietary intake, mobility, psychological stress, or acute disease and neuropsychological problems. A score > 12 indicates normal nutritional status; between 8 and 11 indicates a risk of malnutrition; < 7 indicates malnutrition.

Lastly, in terms of congestion, all patients are assessed for congestion using clinical variables (a mean score of 8 points on the EVEREST scale indicates moderate congestion), and additional assessments are conducted in 30% of patients using pulmonary and vena cava ultrasound. Most patients are treated with intravenous loop diuretics, preferably by bolus. In some cases, it is necessary to combine these with other diuretics, with the most frequently used being thiazide (21%), followed by acetazolamide (9%), and aldosterone antagonists at diuretic doses (5%). Some 7% of the patients are treated with hypertonic saline solution plus furosemide as a decongestive strategy and up to 30% with intravenous iron. Few patients require haemodynamic support, non-invasive ventilation, device implants, or surgery.

DiscussionThe inclusion of the first 1000 patients in the RICA-2 registry shows us that patients with HF treated in IM departments continue to be older patients with multiple comorbidities and with adequate representation between the sexes, something which is not always true for all observational studies or in HF clinical studies, where women are often under-represented.33,34 The most common type of HF according to LVEF in IM departments remains HFpEF7 though it is notable that compared to the historic cohort, there is an increase in patients with HFrEF. Despite the logical similarities between the RICA historic cohort and the contemporary RICA-2 cohort, some differences have been observed. Some of these can be justified, in part, by the fact that RICA-2 includes stable patients enrolled via out-patient services (which was not true for RICA) and perhaps for this reason there are more patients in NYHA functional class II, with better baseline kidney function, and with lower natriuretic peptides levels. Other differences are due to therapeutic advances that HF was undergone in recent decades with the appearance of ARNIs for HFrEF and SGLT2i for the whole spectrum of LVEF. For this reason, the prescription of these medications has clearly increased in RICA-2, as has another of the four pillars of HFrEF treatment, namely aldosterone antagonists. In terms of congestion, it is notable that this is increasingly more assessed via clinical ultrasound as a supplement to the physical examination, though solid scientific evidence is still lacking to be able to recommend its use as a guideline for decongestion.35 We must also highlight that one third of patients receive furosemide doses of 80 mg or higher, which could be a surrogate marker of diuretic resistance22 and could justify the use of early combined diuretic therapy as indicated in the results of recent clinical trials.36,37 Something new that the RICA-2 registry should provide is the assessment of other dimensions not evaluated in the RICA registry and perhaps less examined to date, such as frailty, nutrition and their impact on patients prognosis.38,39

Regarding patient prognosis (mortality and re-hospitalisation), it is still early to tell whether RICA-2 patients will have a better or worse prognosis than those from RICA, as a large number of patients are yet to be included, as well as full follow-up completed, to be able to make this assessment. It is noteworthy that the percentage of patients being monitored by UMIPIC has increased by 40%, a care model that has shown excellent benefits for the entire spectrum of HF patients.12,40–42

The major strength of RICA-2 is its representation of HF patients treated in real clinical practice in internal medicine, including patients with chronic and acute HF. As the number of patients included in RICA-2 increases and as its follow-up period does too, it will be possible to better know the clinical situation, respond to new questions, and generate new hypotheses. On the other hand, RICA-2 has the same limitations as all observational studies and registries, offering a lower level of scientific evidence than that provided by clinical trials, despite which it still provides valuable supplementary information.3,4

ConclusionsIn conclusion, the RICA-2 registry represents a contemporary cohort of patients that provides us with clinical, epidemiological, and prognostic information about patients with HF, both chronic and acute, treated in IM departments.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific funding from agencies from the public sector, commercial sector, or not-for-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez: Á Sánchez-de-Alcázar-del-Río, MI Páez-Rubio; Hospital de la Serranía de Ronda: G Ropero-Luis, C Hidalgo-López; Hospital de Antequera: MA García-Ordóñez, J Olmedo-Llanes; Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena: P Salamanca, D García-Calle, R Ruiz-Hueso, I Bravo-Candela; Hospital Costa del Sol: D Fernández-Bermúdez; Hospital Universitario de Puerto Real: M Guzman-Garcia, C Jarava-Luque; Hospital Universitario San Agustín: R Martínez-Gutiérrez, A Arenas-Iglesias; Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves: F Gutiérrez-Cabello, A Bustos-Merlo; Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas: CM Sánchez-Cano.

Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa: M Sánchez, L Esterellas; Hospital Ernest Lluch de Calatayud: A Crestelo.

Hospital Valle del Nalón: I Suárez-Pedreira, R Arceo-Solis, D Valiente-Vena; Hospital del Oriente de Asturias: J Monte-Armenteros, Francisco Trapiello-Valbuena; Hospital de Jarrio: J Rugele-Niño, D Rodríguez-de-Olmedo; Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias: Á González-Franco, EE Rodríguez-Ávila.

Hospital Universitario Dr. Negrín de Gran Canaria: A Conde-Martel, JM García-Vallejo, S González-Sosa; Hospital Universitario Ntra Sra La Candelaria: MF Dávila-Ramos, R Hernández-Luis.

Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete: J Gómez-Garrido, M García-Sánchez; Hospital Virgen de la Luz de Cuenca: L Jiménez-de-la-Cruz, AB Mañogil-Sánchez, I Zamora-Alarcón.

Complejo asistencial de Ávila: HF Mendoza-Ruiz-de-Zuazu, C Sánchez-Sánchez, L Vera-Bernal; Hospital Provincial de Ávila: C Calleja-Subirán; Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Soria: M Carrera-Izquierdo; Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León: A Muela-Molinero, ÁL Martínez-González.

Hospital Universitari Dr. Josep Trueta de Girona: A Armengou-Arxe; Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol de Badalona: G Guix-Camps, X Garcia-Calvo; Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona: MM Real-Álvarez, JM Camarón-Mallén; Fundació Hospital de l’Esperit Sant: A Sánchez-Biosca, DC Quiroga-Parada; Hospital Clinic de Barcelona: A Suárez-Lombraña, A Aldea-Parés; Hospital De La Santa Creu i Sant Pau: B Garrigasait-Vilaseca; Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge: D Chivite-Guillen; Hospital de Terrassa (Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa): RM Borrallo-Almansa, E Falcó-Puig; Hospital de Olot i comarcal de la Garrotxa: JC Trullàs; Hospital Municipal de Badalona: A Serrado, D Cuartero; Pius Hospital de Valls: T Moreno-López, F Fernández-Muixi.

Hospital de Manises: MC Moreno-García; Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe: V Mittelbrunn-Alquézar, C Puig-Navarro y C Sesmero-García; Hospital Universitario de Torrevieja: JL Corcoles-Satorre, M Montesinos-Aldeguer, JC Blázquez-Encinar; Hospital San Vicente del Raspeig: FA Camarasa-Garcia, E Linares-Albert; Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia: J Pérez-Silvestre, A Nebot-Ariño; Hospital Vega Baja de Orihuela: JM Cepeda-Rodrigo, E Martínez-Birlanga; Hospital de La Ribera de Alzira: JA Arazo-Alcaide, L Lorente.

Hospital Universitario de Badajoz: JC Arévalo-Lorido.

Hospital Lucus Augusti: JM Cerqueiro-González; Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense: RC Gómez-Fernández; Hospital de Monforte de Lemos: ML López-Reboiro; Hospital Rivera Povisa: ML Valle-Feijoo, M Costas-Vila; Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña: I Rodriguez-Osorio, B Seoane-Gonzalez; Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña: SJ Freire-Castro, S Roca-Paz, P Vázquez-Rodríguez.

Hospital Universitario San Pedro: R Baeza-Trinidad, D Mosquera-Lozano; Hospital de Calahorra: P Mendoza-Roy.

Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía de San Sebastián de los Reyes: L Soler-Rangel, M Vázquez-Ronda; Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos: M Yebra-Yebra, M Asenjo; Hospital Universitario de Getafe: J Casado-Cerrada, D Abad-Pérez; Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro de Majadahonda: E Montero-Hernández; Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal: P Llacer-Iborra, L Manzano; Hospital Infanta Cristina (Parla): MP García-de-la-Torre-Rivera, F Deodati; Hospital Clínico San Carlos: M Méndez-Bailon, A Cobos; Hospital Universitario de Torrejón: I Morrás-de-la-Torre; Vithas Pardo de Aravaca: I García-Fernández-Bravo, M Martinez-Martinez-Colubi; Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada: JA Satue-Bartolomé, S Gutiérrez-Barrera; Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre: F Aguilar-Rodríguez; Hospital Universitario de Móstoles: J Abellán-Martínez; Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz: A Albiñana-Pérez.

Hospital Universitario De Navarra: T Carrasquer-Pirla, D Aguiar-Cano.

Hospital Universitário São João, Porto: JP Ferreira, F Nóvoa; Hospital Eduardo Santos Silva, Vila Nova de Gaia: J Mascarenhas, J Pimenta.