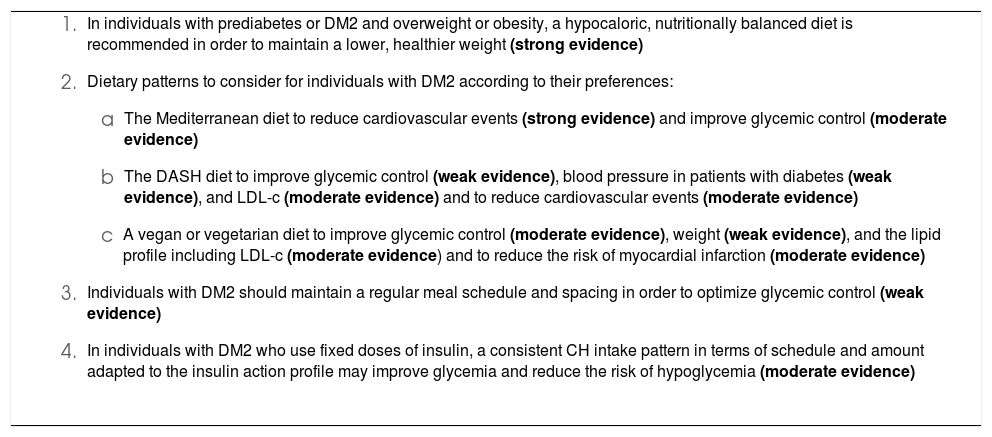

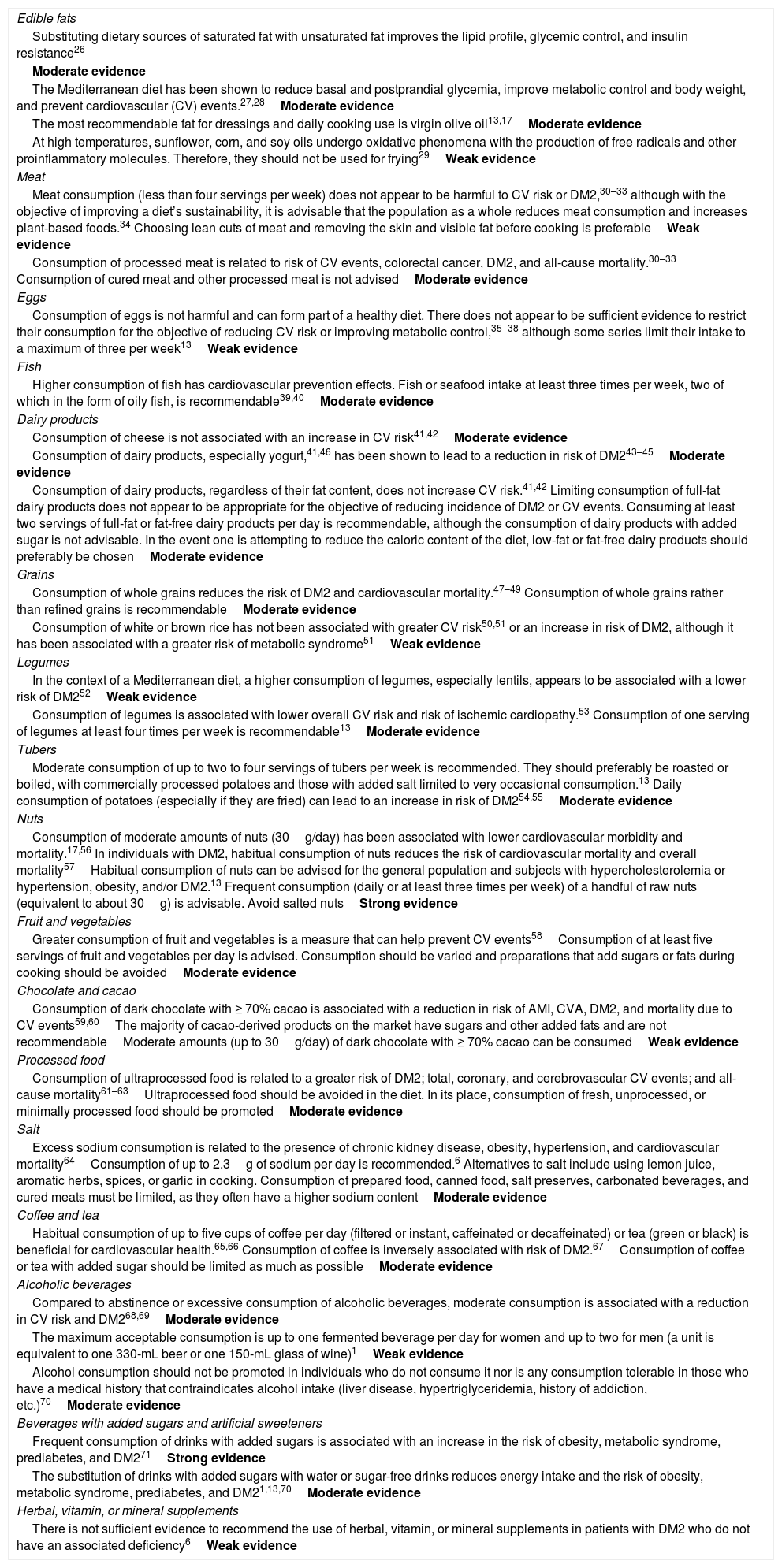

Adequate lifestyle changes significantly reduce the cardiovascular risk factors associated with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Therefore, healthy eating habits, regular physical activity, abstaining from using tobacco, and good sleep hygiene are recommended for managing these conditions. There is solid evidence that diets that are plant-based; low in saturated fatty acids, cholesterol, and sodium; and high in fiber, potassium, and unsaturated fatty acids are beneficial and reduce the expression of cardiovascular risk factors in these subjects. In view of the foregoing, the Mediterranean diet, the DASH diet, a low-carbohydrate diet, and a vegan-vegetarian diet are of note. Additionally, the relationship between nutrition and these metabolic pathologies is fundamental in targeting efforts to prevent weight gain, reducing excess weight in the case of individuals with overweight or obesity; and personalizing treatment to promote patient empowerment.

This document is the executive summary of an updated review that includes the main recommendations for improving dietary nutritional quality in people with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus. The full review is available on the webpages of the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis (SEA, for its initials in Spanish), the Spanish Diabetes Society (SED, for its initials in Spanish), and the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI, for its initials in Spanish).

Los cambios adecuados del estilo de vida reducen significativamente los factores de riesgo cardiovascular asociados a la prediabetes y diabetes mellitus tipo 2, por lo que en su manejo se debe recomendar un patrón saludable de alimentación, actividad física regular, sin consumo de tabaco, y una buena higiene del sueño. Hay una sólida evidencia de que los patrones alimentarios de base vegetal, bajos en ácidos grasos saturados, colesterol y sodio, con un alto contenido en fibra, potasio y ácidos grasos insaturados son beneficiosos y reducen la expresión de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular en estos sujetos. En este contexto destacan la dieta mediterránea, la dieta DASH, la dieta baja en hidratos de carbono y la dieta vegano-vegetariana. Adicionalmente en la relación entre nutrición y estas patologías metabólicas es fundamental dirigir los esfuerzos a prevenir la ganancia de peso o a reducir su exceso en caso de sobrepeso u obesidad, y personalizar el tratamiento para favorecer el empoderamiento del paciente.

Este documento es un resumen ejecutivo de una revisión actualizada que incluye las principales recomendaciones para mejorar la calidad nutricional de la alimentación en las personas con prediabetes o diabetes mellitus tipo 2, disponible en las páginas web de la Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis (SEA), la Sociedad Española de Diabetes (SED) y la Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna (SEMI).

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<