Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and heart failure (HF) have a worse prognosis despite therapeutic advances in both diseases. Sodium-glucose co-transporter type 2 and GLP-1 receptor agonists have shown cardiovascular benefits and they have been positioned as the first step in the treatment of DM in patients with HF or high cardiovascular risk. However, in the pivotal trials the majority of patients receive concomitant treatment with metformin. Randomized clinical trials have not yet been developed to assess the prognostic impact of metformin at the cardiovascular level. Our objective has been centered in analyzing whether patients with DM and acute HF who receive treatment with metformin at the time of discharge may have a better prognosis at one year of follow-up.

MethodsProspective cohort trial using the combined analysis of the two main Spanish HF registries, the EAHFE Registry (Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments) and the RICA (National Registry of Patients with Heart Failure).

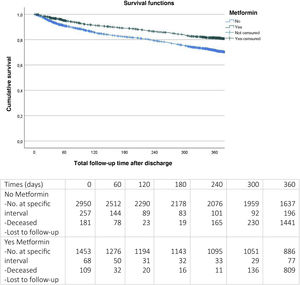

Results33% (1453) of a total of 4403 patients with DM type 2 received treatment with metformin. This group presents significantly lower mortality after one year of treatment (22 versus 32%; Log Rank test P < 0.001). In the adjusted analysis of mortality, patients receiving treatment with metformin have lower mortality at one year of follow-up regardless of the rest of the variables (RR 0,814; 95%IC 0,712–0,930; P < 0.01).

ConclusionsPatients with DM type 2 and acute HF who receive metformin have a better prognosis after one year of follow-up, so we believe that this drug should continue to be a fundamental pillar in the treatment of these patients.

Los pacientes con diabetes mellitus (DM) e insuficiencia cardiaca (IC) presentan peor pronóstico a pesar de los avances terapéuticos en ambas enfermedades. Los inhibidores del cotransportador sodio-glucosa tipo 2 y agonistas del receptor de GLP-1 han demostrado beneficios cardiovasculares y se han posicionado como primer escalón en el tratamiento de DM en pacientes con IC o elevado riesgo cardiovascular. Sin embargo, en los ensayos pivotales la mayoría de pacientes recibe tratamiento concomitante con metformina. Todavía no se han desarrollado ensayos clínicos aleatorizados para evaluar el impacto pronóstico de la metformina a nivel cardiovascular. Nuestro objetivo fue analizar si los pacientes con DM e IC aguda que reciben tratamiento con metformina en el momento del alta pueden presentar mejor pronóstico al año de seguimiento.

MétodosEnsayo de cohortes prospectivo mediante el análisis combinado de los dos principales registros españoles de IC, el Registro EAHFE (Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments) y el RICA (Registro Nacional de Pacientes con Insuficiencia Cardiaca).

ResultadosDe un total de 4403 pacientes con DM tipo 2, recibió tratamiento con metformina el 33% (1453). Este grupo presentó mortalidad significativamente inferior al año de tratamiento (22 versus 32%; test de Log Rank P <,001). En el análisis ajustado de mortalidad, los pacientes que recibieron tratamiento con metformina presentaron menor mortalidad al año de seguimiento independientemente del resto de variables (RR 0,814; IC95% 0,712–0,930; P <,01).

ConclusionesLos pacientes con DM tipo 2 e IC aguda que reciben metformina presentan mejor pronóstico al año de seguimiento, por lo que consideramos que este fármaco debe continuar siendo un pilar fundamental en el tratamiento de estos pacientes.

The prevalence and incidence of heart failure (HF) and diabetes mellitus (DM) have progressively increased in the last decade.1,2 Type 2 DM is considered an independent factor for the development of HF3 and is in turn associated with a worse HF prognosis.4,5 In patients hospitalized due to HF, DM is associated with a longer hospital stay, higher readmission rate,6,7 and greater associated comorbidity.7,8 However, the role of DM in in-hospital and long-term mortality in patients with HF remains controversial.9,10 Data from the National Registry of Patients with Heart Failure (RICA, for its initials in Spanish) show that patients with type 2 DM have higher readmission rates due to HF and higher long-term mortality compared to those who do not have the disease, though in-hospital mortality appears to be equal in both groups.4

The neurohormonal treatment that have become in recent years has improved the prognosis of patients with HF.11 Two groups of hypoglycemic drugs—sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists (GLP-1ra)—have demonstrated cardiovascular benefits in patients with and without type 2 DM.12–27 The most recent European guidelines on DM28 recommend these drugs as initial treatment in patients with high or very high cardiovascular risk who are not yet receiving metformin.

Metformin is a classic drug in type 2 DM treatment.29,30 Given the evidence that it decreases macrovascular complications,31 the guidelines recommend it as the first treatment option in most patients. However, its effect on the prognosis of patients with HF has yet to be investigated. The principal aim of this study was to analyze whether patients with DM and acute HF who receive treatment with metformin at discharge have a better prognosis at one year of follow-up.

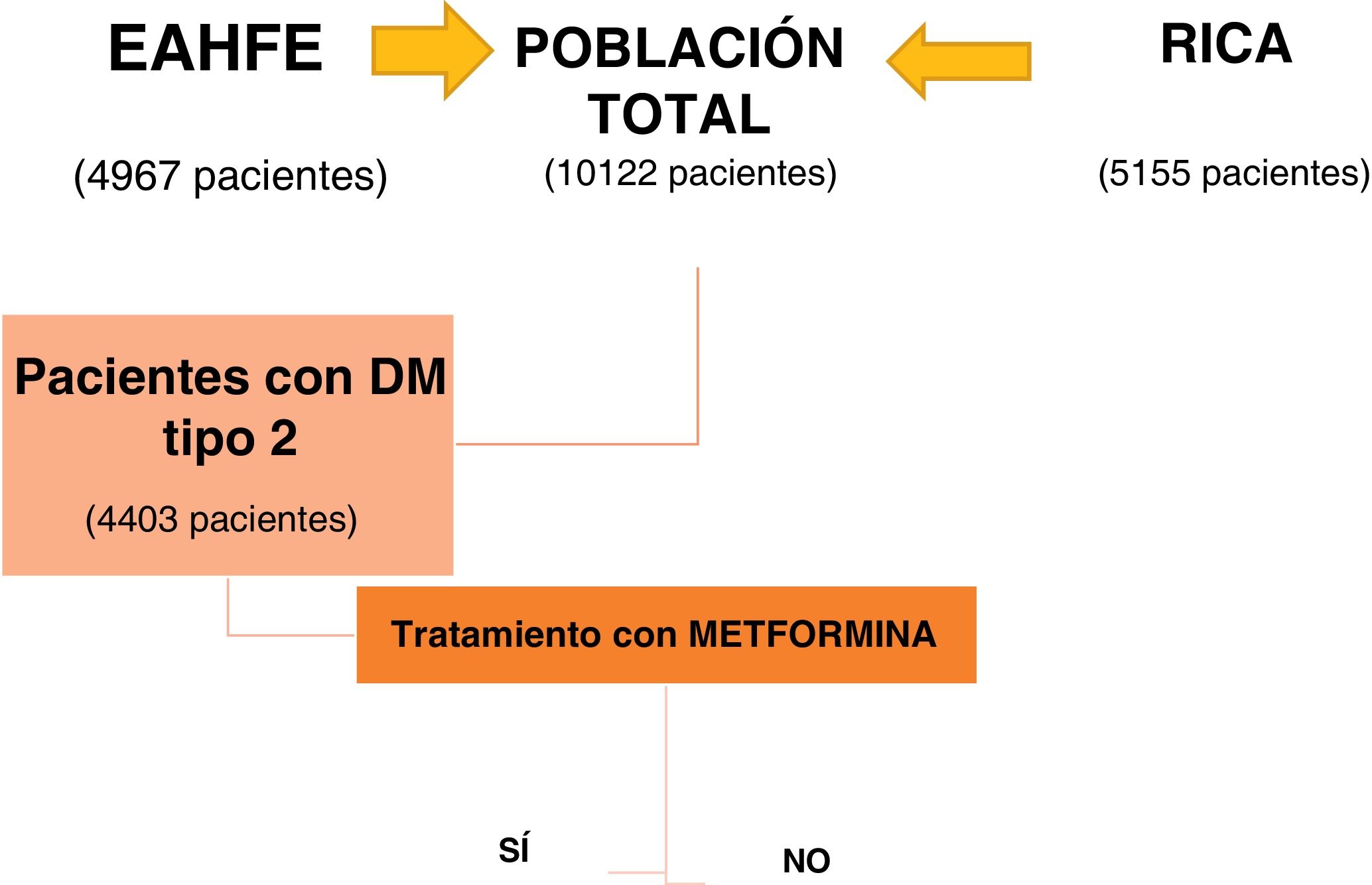

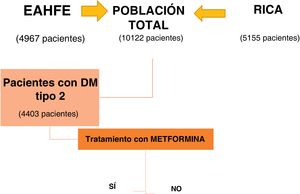

Material and methodsDesign and data sourceThis work is a prospective, observational cohort study which combines data from patients included in the two main Spanish HF registries: the Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments (EAHFE) Registry and the RICA Registry. This is an effectiveness which aims to evaluate the use of metformin in a real-world population and its prognostic impact at one year of follow-up.

The EAHFE Registry is a multicenter, non-interventional, analytical cohort study with prospective follow-up.32–34 It is managed by the HF working group of the Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine (SEMES, for its initials in Spanish). A total of 45 Spanish hospital emergency departments (HED) participate in it and it includes 18,370 patients diagnosed with acute heart failure (AHF) between 2007 and 2018 during six one- to two-month recruitment periods every two or three years. This registry does not include any planned interventions nor does it change the care received from the attending physician, which is based on clinical practice guidelines and each hospital’s protocols.

The RICA Registry is a multicenter, prospective cohort study35,36 by the HF and Atrial Fibrillation Working Group of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI). Fifty-two public and private centers across Spain participate in it and it has been active since 2008. It includes unique consecutive patients older than 50 years of age with a diagnosis of HF upon hospital discharge after an episode of decompensation of new-onset HF, in accordance with the definition in the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines.37

Study populationThis work included all patients in the RICA Registry up to 2018 and the populations from EAHFE-5 (inclusion period from January 1 to February 29, 2016, with the participation of 30 HED) and EAHFE-6 (inclusion period from February 1 to March 31, 2018, with the participation of 34 HED) in which data related to DM treatment were collected. After completing the necessary procedures for authorization to process data from both registries, a joint database was created that maintained all the common variables and eliminated those which did not coincide, in order to jointly analyze both study populations. Within this population group, patients with type 2 DM (if it was recorded as a previous diagnosis, if they took hypoglycemic drugs, or if their glycated hemoglobin concentration upon admission was >6.5%) were selected as the study population.

VariablesClinical and treatment variables defined in other previous articles on the RICA4 and EAHFE registries38 were collected. The follow-up period was 12 months from hospital discharge from the index AHF episode. All-cause mortality at one year was recorded by consulting the medical record or direct contact. If necessary, the death was verified in the social security registry, as patients who have passed away are deregistered the day after death. Patients who died in the hospital during the index episode were excluded from the study. To calculate the follow-up time variable, either the study end date (one year of follow-up after the index episode), the date of death, or the date of loss to follow-up if it occurred before one year (censure date for the survival study) were used.

Ethical considerationsThe RICA Registry protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Reina Sofía University Hospital of Córdoba (Spain) and the EAHFE Registry protocol was approved by the Central University Hospital of Asturias (Oviedo, Spain). The reference numbers for phases 5 and 6 are 160/15 and 205/17, respectively. Data were entered into anonymized databases and have been managed according to RD 1720/2007, which implements Organic Law 15/1999, of December 13, on Personal Data Protection.4,35,36 The study was conducted in strict compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. As they are observational cohort studies, both registries followed the STROBE guidelines for this method.

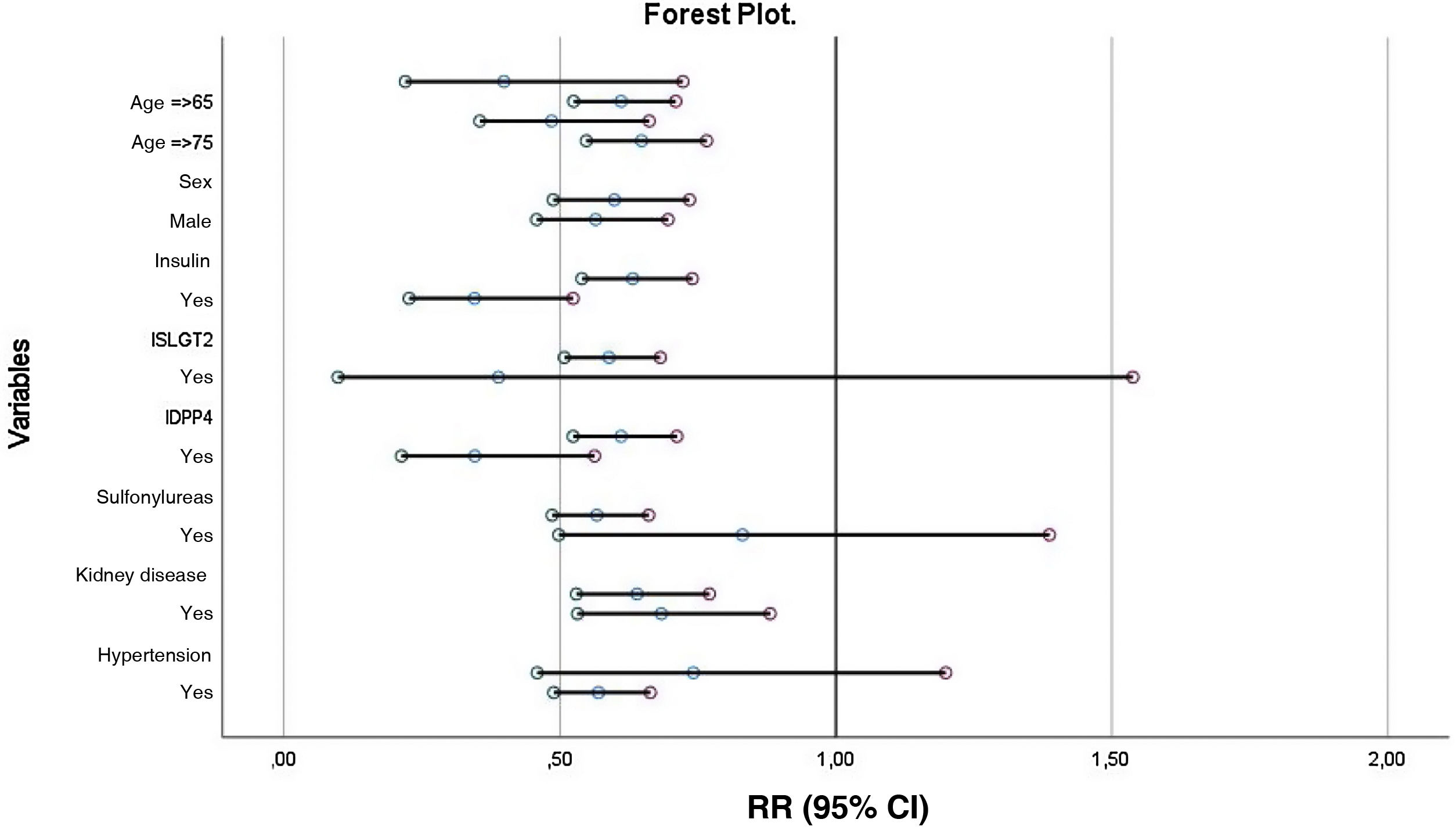

Statistical analysisQualitative variables are expressed as frequency and percentage. Continuous quantitative variables are shown as mean and standard deviation after performing the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. The bivariate comparative analysis was conducted using the chi-square test when there were two categorical tests and ANOVA for the comparison of quantitative variables from more than two groups. For the mortality analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank test were calculated. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was conducted using a conditional backward stepwise method for variables shown to have a statistically significant relationship to probability of death on the univariate analysis. The risk associated with all-cause death in patients in treatment with metformin was expressed as relative risk (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) compared to patients who did not receive metformin. A forest plot was created to evaluate how metformin behaved in different subpopulations of patients. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS, version 26.0, IBM, Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was established as P < 0.05 or if the 95% CI of the HR did not include the value of 1.

ResultsOf the 10,122 patients included by combining the EAHFE and RICA databases, 4403 patients had type 2 DM, 43.5% of the total. The subgroup analysis was conducted based on whether or not they received treatment with metformin at discharge from the index decompensation episode (Fig. 1).

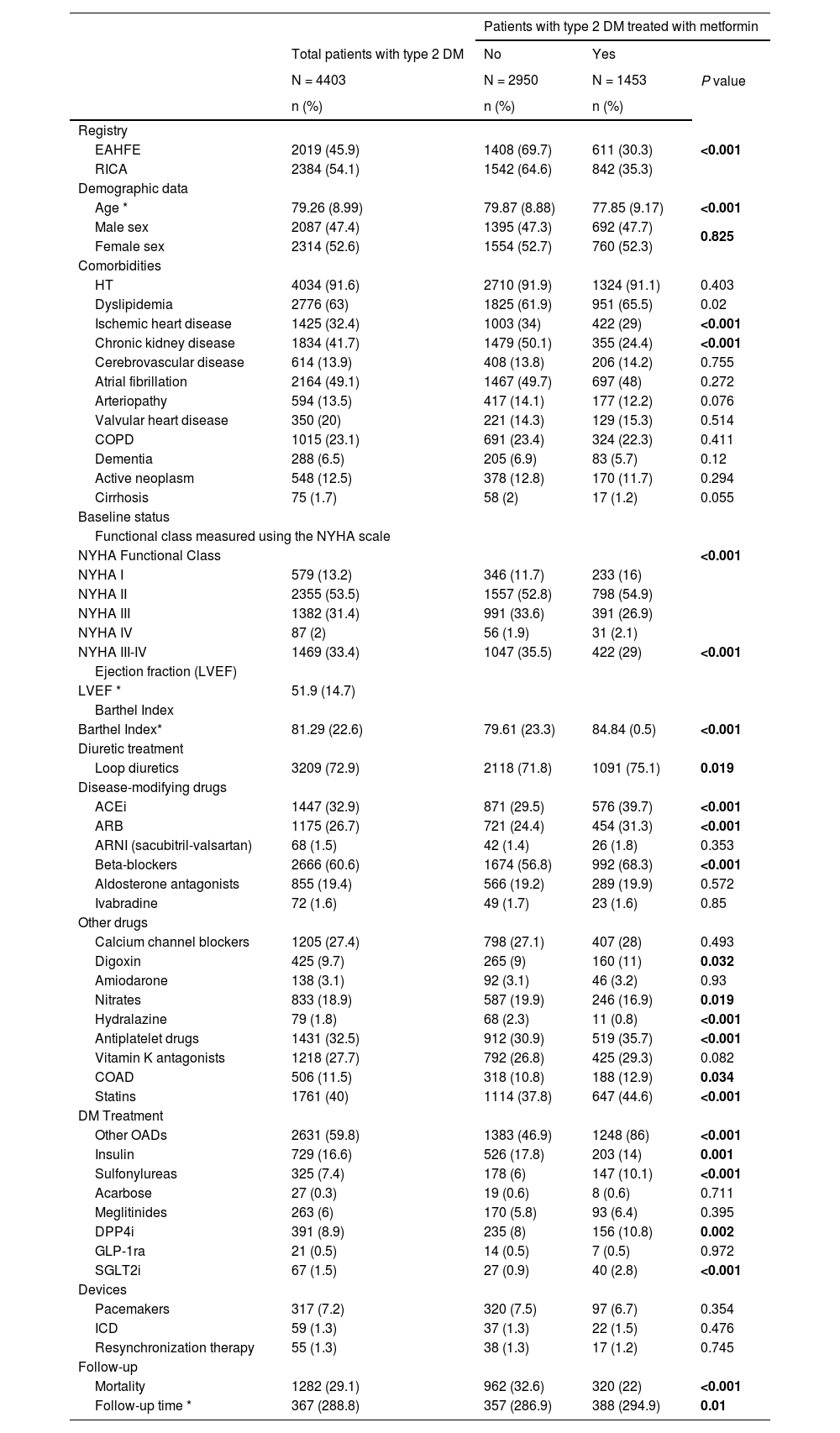

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the group of patients with type 2 DM and both subgroups. The 1453 patients who received treatment with metformin after hospital discharge represent 33% of all patients with type 2 DM. These patients were younger (77 vs 79 years, P < 0.001), had less comorbidity, and the prevalence of ischemic heart disease (29% versus 34%, P < 0.011) and chronic kidney disease (24% versus 50%; P < 0.01) was significantly lower. In addition, they have a better functional status evidenced by a lower percentage of NYHA III-IV functional class (35% versus 29%; P < 0.001) and higher Barthel Index scores (from 84 versus 79; P < 0.01). The drugs that both groups received for HF treatment are shown in the table. In regard to DM treatment, the metformin group received associated oral antidiabetics more often and there was a lower percentage of insulin use (Table 1).

Description of the characteristics of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and comparison of patients with type 2 DM according to whether they are treated with metformin or not.

| Patients with type 2 DM treated with metformin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients with type 2 DM | No | Yes | P value | |

| N = 4403 | N = 2950 | N = 1453 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Registry | ||||

| EAHFE | 2019 (45.9) | 1408 (69.7) | 611 (30.3) | <0.001 |

| RICA | 2384 (54.1) | 1542 (64.6) | 842 (35.3) | |

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age * | 79.26 (8.99) | 79.87 (8.88) | 77.85 (9.17) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 2087 (47.4) | 1395 (47.3) | 692 (47.7) | 0.825 |

| Female sex | 2314 (52.6) | 1554 (52.7) | 760 (52.3) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| HT | 4034 (91.6) | 2710 (91.9) | 1324 (91.1) | 0.403 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2776 (63) | 1825 (61.9) | 951 (65.5) | 0.02 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1425 (32.4) | 1003 (34) | 422 (29) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1834 (41.7) | 1479 (50.1) | 355 (24.4) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 614 (13.9) | 408 (13.8) | 206 (14.2) | 0.755 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2164 (49.1) | 1467 (49.7) | 697 (48) | 0.272 |

| Arteriopathy | 594 (13.5) | 417 (14.1) | 177 (12.2) | 0.076 |

| Valvular heart disease | 350 (20) | 221 (14.3) | 129 (15.3) | 0.514 |

| COPD | 1015 (23.1) | 691 (23.4) | 324 (22.3) | 0.411 |

| Dementia | 288 (6.5) | 205 (6.9) | 83 (5.7) | 0.12 |

| Active neoplasm | 548 (12.5) | 378 (12.8) | 170 (11.7) | 0.294 |

| Cirrhosis | 75 (1.7) | 58 (2) | 17 (1.2) | 0.055 |

| Baseline status | ||||

| Functional class measured using the NYHA scale | ||||

| NYHA Functional Class | <0.001 | |||

| NYHA I | 579 (13.2) | 346 (11.7) | 233 (16) | |

| NYHA II | 2355 (53.5) | 1557 (52.8) | 798 (54.9) | |

| NYHA III | 1382 (31.4) | 991 (33.6) | 391 (26.9) | |

| NYHA IV | 87 (2) | 56 (1.9) | 31 (2.1) | |

| NYHA III-IV | 1469 (33.4) | 1047 (35.5) | 422 (29) | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction (LVEF) | ||||

| LVEF * | 51.9 (14.7) | |||

| Barthel Index | ||||

| Barthel Index* | 81.29 (22.6) | 79.61 (23.3) | 84.84 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Diuretic treatment | ||||

| Loop diuretics | 3209 (72.9) | 2118 (71.8) | 1091 (75.1) | 0.019 |

| Disease-modifying drugs | ||||

| ACEi | 1447 (32.9) | 871 (29.5) | 576 (39.7) | <0.001 |

| ARB | 1175 (26.7) | 721 (24.4) | 454 (31.3) | <0.001 |

| ARNI (sacubitril-valsartan) | 68 (1.5) | 42 (1.4) | 26 (1.8) | 0.353 |

| Beta-blockers | 2666 (60.6) | 1674 (56.8) | 992 (68.3) | <0.001 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 855 (19.4) | 566 (19.2) | 289 (19.9) | 0.572 |

| Ivabradine | 72 (1.6) | 49 (1.7) | 23 (1.6) | 0.85 |

| Other drugs | ||||

| Calcium channel blockers | 1205 (27.4) | 798 (27.1) | 407 (28) | 0.493 |

| Digoxin | 425 (9.7) | 265 (9) | 160 (11) | 0.032 |

| Amiodarone | 138 (3.1) | 92 (3.1) | 46 (3.2) | 0.93 |

| Nitrates | 833 (18.9) | 587 (19.9) | 246 (16.9) | 0.019 |

| Hydralazine | 79 (1.8) | 68 (2.3) | 11 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 1431 (32.5) | 912 (30.9) | 519 (35.7) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 1218 (27.7) | 792 (26.8) | 425 (29.3) | 0.082 |

| COAD | 506 (11.5) | 318 (10.8) | 188 (12.9) | 0.034 |

| Statins | 1761 (40) | 1114 (37.8) | 647 (44.6) | <0.001 |

| DM Treatment | ||||

| Other OADs | 2631 (59.8) | 1383 (46.9) | 1248 (86) | <0.001 |

| Insulin | 729 (16.6) | 526 (17.8) | 203 (14) | 0.001 |

| Sulfonylureas | 325 (7.4) | 178 (6) | 147 (10.1) | <0.001 |

| Acarbose | 27 (0.3) | 19 (0.6) | 8 (0.6) | 0.711 |

| Meglitinides | 263 (6) | 170 (5.8) | 93 (6.4) | 0.395 |

| DPP4i | 391 (8.9) | 235 (8) | 156 (10.8) | 0.002 |

| GLP-1ra | 21 (0.5) | 14 (0.5) | 7 (0.5) | 0.972 |

| SGLT2i | 67 (1.5) | 27 (0.9) | 40 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Devices | ||||

| Pacemakers | 317 (7.2) | 320 (7.5) | 97 (6.7) | 0.354 |

| ICD | 59 (1.3) | 37 (1.3) | 22 (1.5) | 0.476 |

| Resynchronization therapy | 55 (1.3) | 38 (1.3) | 17 (1.2) | 0.745 |

| Follow-up | ||||

| Mortality | 1282 (29.1) | 962 (32.6) | 320 (22) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up time * | 367 (288.8) | 357 (286.9) | 388 (294.9) | 0.01 |

Acronyms: EAHFE: Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments Registry; RICA: National Registry of Patients with Heart Failure (Registro Nacional de Pacientes con Insuficiencia Cardiaca in Spanish); HT: hypertension; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NYHA: New York Heart Association; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blockers; ARNI: angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; DOAC: Direct oral anticoagulants; DM: diabetes mellitus; OADs: oral antidiabetics; DPP4i: dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; GLP-1ra: Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; SGLT2i: sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Bold values mean statistically significant p values.

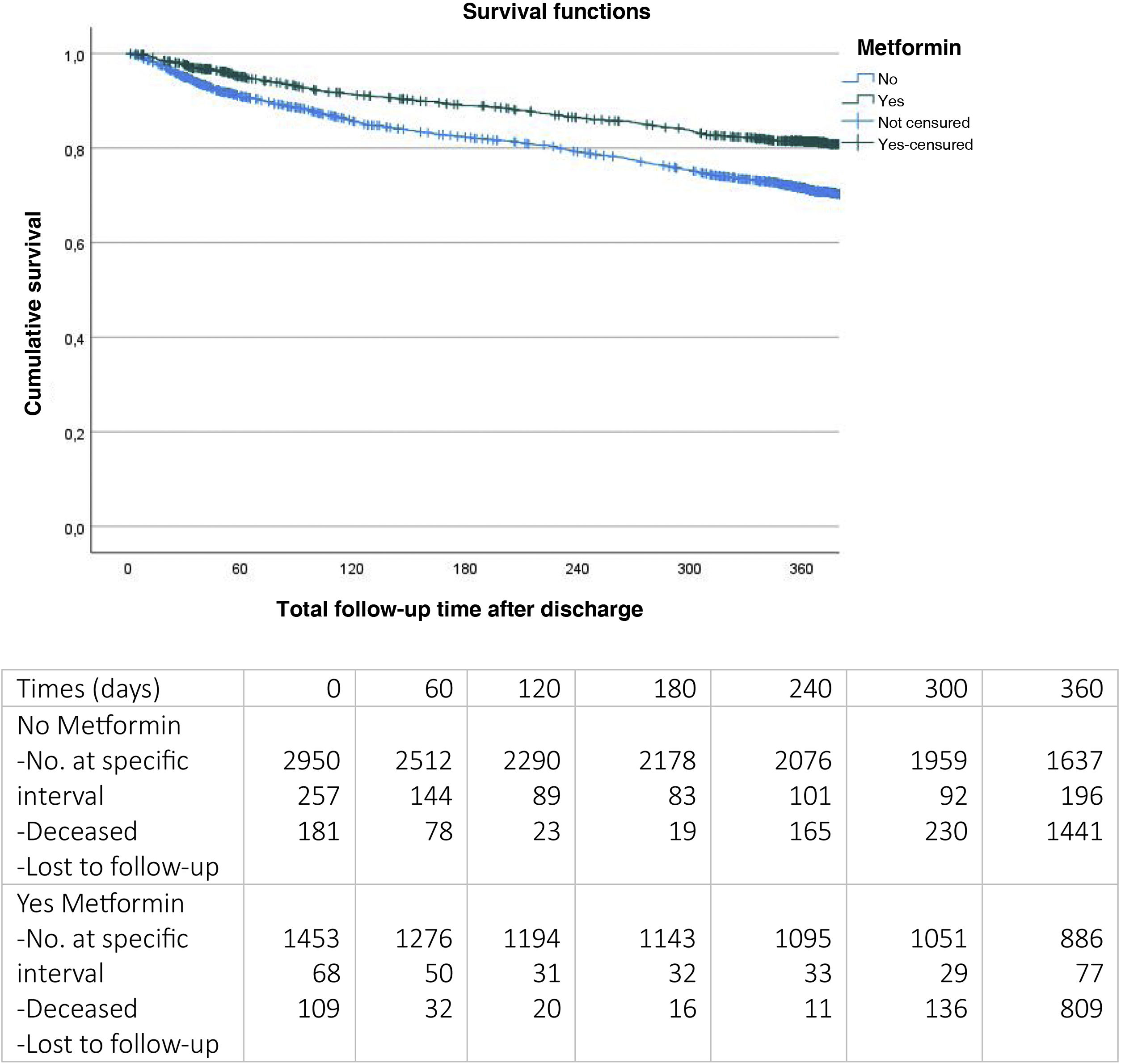

After 12 months of follow-up (Fig. 2), it was observed that patients with metformin upon discharge had significantly lower mortality (22% versus 32%, log-rank test P < 0.001).

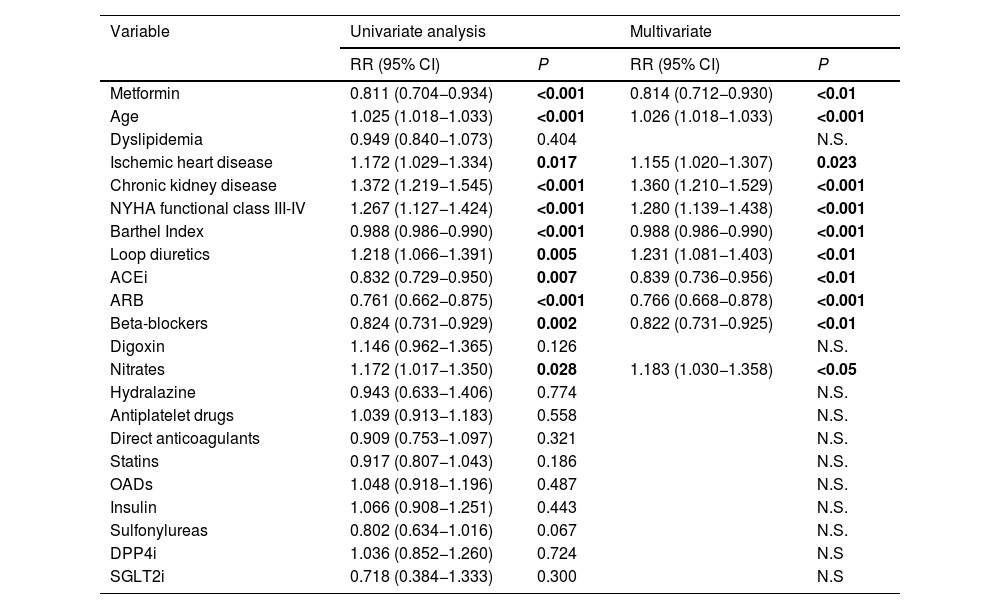

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed on mortality at one-year of follow-up (Table 2). In the adjusted analysis, the patients who had greater mortality at one-year of follow-up were older (RR 1.025; 95% CI 1.018–1.033; P < 0.001), more often had associated comorbidity such as ischemic heart disease (RR 1.155; 95% CI 1.020–1.307; P = 0.023) or chronic kidney disease (RR 1.360; 95% CI 1.210–1.529; P < 0.001), and had worse functional class (NYHA functional class III–IV) (RR 1.280; 95% CI 1.139–1.438; P < 0.001). In this analysis, treatment with ACEi (RR 0.839; 95%CI 0.736–0.956; P < 0.01), ARB (RR 0.766; 95%CI 0.668–0.878; P < 0.001), beta blockers (RR 0.822; 95% CI 0.731–0.925; P < 0.01), and metformin were protective factors.

Cox univariate and multivariate regression analysis for mortality at one year.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | P | RR (95% CI) | P | |

| Metformin | 0.811 (0.704−0.934) | <0.001 | 0.814 (0.712−0.930) | <0.01 |

| Age | 1.025 (1.018−1.033) | <0.001 | 1.026 (1.018−1.033) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.949 (0.840−1.073) | 0.404 | N.S. | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.172 (1.029−1.334) | 0.017 | 1.155 (1.020−1.307) | 0.023 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.372 (1.219−1.545) | <0.001 | 1.360 (1.210−1.529) | <0.001 |

| NYHA functional class III-IV | 1.267 (1.127−1.424) | <0.001 | 1.280 (1.139−1.438) | <0.001 |

| Barthel Index | 0.988 (0.986−0.990) | <0.001 | 0.988 (0.986−0.990) | <0.001 |

| Loop diuretics | 1.218 (1.066−1.391) | 0.005 | 1.231 (1.081−1.403) | <0.01 |

| ACEi | 0.832 (0.729−0.950) | 0.007 | 0.839 (0.736−0.956) | <0.01 |

| ARB | 0.761 (0.662−0.875) | <0.001 | 0.766 (0.668−0.878) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 0.824 (0.731−0.929) | 0.002 | 0.822 (0.731−0.925) | <0.01 |

| Digoxin | 1.146 (0.962−1.365) | 0.126 | N.S. | |

| Nitrates | 1.172 (1.017−1.350) | 0.028 | 1.183 (1.030−1.358) | <0.05 |

| Hydralazine | 0.943 (0.633−1.406) | 0.774 | N.S. | |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 1.039 (0.913−1.183) | 0.558 | N.S. | |

| Direct anticoagulants | 0.909 (0.753−1.097) | 0.321 | N.S. | |

| Statins | 0.917 (0.807−1.043) | 0.186 | N.S. | |

| OADs | 1.048 (0.918−1.196) | 0.487 | N.S. | |

| Insulin | 1.066 (0.908−1.251) | 0.443 | N.S. | |

| Sulfonylureas | 0.802 (0.634−1.016) | 0.067 | N.S. | |

| DPP4i | 1.036 (0.852−1.260) | 0.724 | N.S | |

| SGLT2i | 0.718 (0.384−1.333) | 0.300 | N.S | |

Acronyms: RR: relative risk; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; NYHA: New York Heart Association; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; ACEi: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: angiotensin receptor blockers; DOAC: direct oral anticoagulants; OAD: oral antidiabetics; DPP4i: dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; GLP-1ra: Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; SGLT2i: sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors.

Bold values mean statistically significant p values.

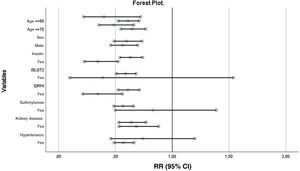

The results of the forest plot are shown in Fig. 2. As can be seen, metformin maintains its protective effect on mortality in most subgroups except for the SGLT2i, sulfonylureas, and medical history of hypertension groups.

Patients who receive treatment with metformin have significantly lower mortality at one year of follow-up (RR 0.814; 95% CI 0.712–0.930; P < 0.01) regardless of the rest of variables (Fig. 3).

DiscussionFirst, it is noteworthy that metformin was prescribed at discharge in just one-third of patients with DM, less than what is to be expected according to clinical practice guidelines (CPG) recommendations. Patients from the EAHFE and RICA registries are cared for in HED or the internal medicine hospitalization ward and tend to have a more geriatric profile than the population included in randomized clinical trials (RCT); namely, they are older, frailer, and have more comorbidities. This difference in the population is a possible explanation for the low prescribing rate in our study. Other population studies have also reported a significant percentage of underuse of drugs such as metformin, GLP-1ra, and SGLT2i.39 They attribute it to the significant percentage of older adult patients in the Spanish population, whose particular characteristics may limit the use of some drugs.

However, the underuse of metformin may also be explained by adherence to CPG or due to fear of adverse effects (AE). This drug is contraindicated when the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and it is recommended to suspend it in severe patients with risk of acute renal failure or metabolic acidosis. The fear of developing AE, in particular lactic acidosis, is the main reason for the tendency toward systematically suspending this drug in hospitalized patients regardless of their clinical situation, despite the fact that scientific evidence in this regard has progressed in recent years. In the past, although some studies already suggested that this relationship could be casual,40 the use of metformin in patients with decompensated or advanced HF (NYHA III-IV) was not recommended in the CPGs. Later, it was demonstrated in registries and observational studies that the risk of this complication is regardless of whether the patient takes metformin or not.41,42 The most recent CPGs on DM28 establish that metformin is safe in all phases of HF with conserved or moderately reduced renal function (GFR > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2) and entails a lower risk of mortality or admission due to HF compared to insulin and sulfonylureas. This document also rejects the risk of lactic acidosis related to this drug.41,43,44

As stated above, metformin was demonstrated to reduce cardiovascular complications in DM, decreasing total and cardiovascular-related mortality by 30%, acute myocardial infarction by 39%, and cerebrovascular accident by 41% in the first ten years following diagnosis.31 However, to date, no RCTs have been conducted that evaluate the cardiovascular effects of metformin. After pivotal studies on GLP-1ra and SGLT2i, these drugs are now included in DM guidelines28 as drugs of choice in patients with DM and very high cardiovascular risk; they are even recommended as initial treatment in some cases. Nevertheless, when these RCTs were conducted, most received concomitant treatment with metformin and its effects together with those of this drug were evaluated. The DANIsh RCT with the Met-HeFT substudy is designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of metformin in patients with chronic HF; it is currently in phase 4. For the first time, it will provide data from an RCT on the risk of lactic acidosis.45 While awaiting its publication, the currently available scientific evidence allows for both HF11 and DM CPGs28 to recommend the use of metformin in this patient profile. The results of this study strengthen this recommendation, as patients with type 2 DM and HF in treatment with metformin had lower mortality at one year of follow-up regardless of the rest of factors. Therefore, the authors believe that prescribing this drug in this group of patients must continue to be a fundamental pillar of treatment and underprescribing due to fear of potential AE must be avoided.

Second, it should be noted that in this study, the percentage of patients in treatment with drugs from the GLP-1ra and SGLT2i groups is very small. This is due to the fact that patient inclusion ended in 2018, before their use became widespread in this patient profile. Although a larger percentage of patients with type 2 DM treated with metformin had associated SGLT2i use than the group without metformin in this study, they were still just 40 patients out of a total of 1453 patients with DM in treatment with metformin. Therefore, it is not believed that the results have been biased due to the influence of this drug group. It would be of interest to conduct this analysis again on the EAHFE and RICA cohorts after 2018, in which the percentage of patients treated with these drug groups would presumably be greater.

This study has several limitations. First, as it is a retrospective analysis, the results are correlational and do not imply causality. Therefore, they only allow for formulating hypotheses. Second, there may be selection bias because patients come from centers which voluntarily joined and because the study period was very extensive. The third limitation is related to a high degree of variability of the participating centers in terms of both structure and management. Indeed, the considerable heterogeneity of management and follow-up strategies for HF in Spain is well-known.46,47 Fourth, the patients’ diagnosis was established according to clinical criteria. Although it was confirmed with natriuretic peptides or echocardiography in most cases, there still is a possibility of diagnostic error. Fifth, assigning patients to groups with and without treatment with metformin was done based on prescribing at the time of discharge, but this aspect was not monitored during follow-up. For this reason, there may be patients who changed group.

Nevertheless, given the experience there is with this drug, we believe that the percentage of patients who may have changed group is small. Sixth, although the patient’s degree of dependence (measured using the Barthel Index) was taken into account in the adjusted models, frailty was not. This aspect has an important impact on older patients and specifically in patients with HF.48,49 Lastly, a sample size estimation was not performed in this analysis. Therefore, it is possible that beta statistical error may have occurred in some estimates. However, given that the results are based on information obtained from the two main multicentric registries of patients with HF in Spain, it is believed they are representative and potentially able to be extrapolated to the whole of the Spanish population.

In conclusion, patients with DM and HF in this study who receive treatment with metformin had lower mortality at one year of follow-up. Therefore, we believe that prescribing this drug in this patient profile must continue to be a fundamental treatment pillar and underprescribing due to fear of potential AE must be avoided.

FundingThis research has not received specific grants from agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.